Our 2021 health heroes

This past year, we have celebrated vaccine rollouts and adapted to evolving public health guidance as the ongoing pandemic nears the two year mark. Masks have become part of our routine. So have vaccine passports and travel restrictions. Through it all, Canada’s health care workers continue to save lives and bring care to those who need it most. And while we no longer stand on balconies, banging pots and pans in their honour, these health care heroes deserve to be celebrated.

Here is the non-exhaustive but hella impressive list of everyday heroes who put extraordinary effort into our best health.

(Related: I Was Vaccine Hesitant. This Is What Changed My Mind.)

Cindy Blackstock

For championing the rights of Indigenous children

Cindy Blackstock has been working tirelessly to uphold Indigenous children’s rights for more than 30 years. In 2021, she had a remarkable win.

Back in 2007, Blackstock, the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, alongside the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), filed a human rights complaint against the federal government, alleging that the disproportionate number of First Nations children in foster care stemmed from inequitable services given to children on reserve. It asked for the government to compensate First Nations families whose children endured Canada’s child welfare system, and to uphold Jordan’s Principle, the legal requirement calling for First Nations children across Canada to access public services without delay or denial.

Two years ago, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal agreed—and declared that the government had to pay $40,000 to each First Nations child unfairly taken from their homes after 2006. (That’s an estimated 50,000 children.) The federal government refused to comply and asked for a judicial review. But in late September, a federal court dismissed that review and upheld the tribunal’s ruling, stating the federal government willfully and recklessly discriminated against Indigenous children.

The fight isn’t over yet: on October 29 of this year, the federal government filed a last-minute appeal to the ruling, then announced that it would resolve the dispute out of court by working with Indigenous groups like the Caring Society. Blackstock, a member of the Gitxsan First Nation in B.C., told CTV she wants to see the government “accept responsibility” for the way it has treated—and continues to treat—First Nations children. “We want this to be the last generation of First Nations kids who are actually hurt by the government directly,” she said.—K.B.

Alice Curitz

For making therapy more inclusive and accessible

At the end of January, nearly a year into a global pandemic that challenged our collective mental health, Alice Curitz founded Our Landing Place, a therapy clinic that prioritizes inclusive, queer-affirming, sex-positive care. The clinic’s six LGBTQ2S+-identified counsellors specialize in working online with queer communities, who are at significantly higher risks for many mental health issues. LGBTQ2S+ youth, for example, experience 14 times the risk of suicide and substance dependency as their heterosexual peers. “You’re asking somebody to be incredibly vulnerable with you when they’re coming to see you for therapy,” she told the CBC in July. Having counsellors who appreciate the particular challenges their patients face, Curitz adds, “can really build that sense of, OK, this is a place [where] I can be me.”

To reach people nationwide, Curitz and Our Landing Place launched Queering Mental Health: A Canadian Perspective, a full-day online conference in April. Participants, including Curitz, homed in on the barriers to mental health services that have affected the LGBTQ2S+ community and been exacerbated during the pandemic. Marginalized people experience higher rates of isolation, economic strain, anxiety and poor access to informed, inclusive and culturally appropriate care.

During this unprecedented time, where socializing has become life-threatening, Curitz’s remedy to distress is connection. Says Curitz, “I believe that connection is what helps us heal and grow.”—M.W.

Dr. Annalee Coakley

For dismantling barriers to getting vaxxed

Close quarters, cold temperatures, fast-paced work and long hours: It’s no surprise meat-packing plants have been hit hard by COVID. At Calgary’s Cargill meat plant, nearly half the workers tested positive in the spring of 2021, while, nearby, the JBS beef plant had reported 650 cases among its 2,500 workers by April 2021. Getting workers vaccinated—and fast—was crucial to stopping more outbreaks.

Enter Dr. Annalee Coakley, who helped organize vaccination efforts at both meat-packing plants (which together process about 70 percent of Canada’s beef). For nearly a decade, Coakley has worked as the physician lead with Calgary’s Mosaic Refugee Health Clinic, leading specialized primary care to support the resettlement needs of the city’s refugee population.

This spring, Coakley also helped set up vaccination clinics in east Calgary, an area of the city with a large population of front-line workers that consistently faced high rates of COVID. The clinic extended its hours for shift workers, didn’t require health cards (which can be an obstacle for undocumented and migrant workers), and had staffers who could speak 72 different languages, in order to eliminate as many barriers as possible to immunization in the community. “They came into the clinic because it was convenient, it was accessible to them,” she said in an interview with the CBC. “They told us that they wouldn’t have gotten the vaccination otherwise.”—R.G.

Dr. Danuta Skowronski

For optimizing our vaccination rollout

In late 2020, Dr. Danuta Skowronski, the epidemiology lead of influenza and emerging respiratory pathogens at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, was poring over data from Pfizer about its COVID-19 vaccine when she spotted something no one else had noticed: the efficacy of the first dose was actually much higher than the company had reported. Pfizer focused on the period immediately after a person received their first shot, when efficacy reached around 50 percent. But immunity keeps mounting in the following days—that’s how vaccines work. Two weeks after the shot, efficacy hit 92 percent.

Dr. Skowronski—who spent the past two decades of her career jumping from one infectious disease outbreak to the next—made a bold recommendation: Canada should postpone the second dose and put every effort into getting more first shots into more arms faster. Her advice led Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization to change its recommended time period between doses to a window of up to four months. “I just felt huge relief,” she says.

This set Canada apart from nearly every other country, including the United States, where experts called for strict adherence to the manufacturer’s recommended three- to four-week window between doses. Canada’s chief science advisor Mona Nemer questioned delaying doses, saying it amounted to a “population-level experiment.”

But as a result of Skowronksi’s advice, Canada’s vaccination rate climbed quickly. And the strategy saved lives. Recently released data from British Columbia and Quebec shows that the decision to delay and mix second doses of COVID-19 vaccines led to strong protection from infection, hospitalization and deaths.—C.F.

(Related: Canada’s Dietitians Are Lacking in Diversity–But Things Are Changing)

The founders of BHEC

For confronting anti-Black racism in Canadian health care

Anti-Black racism is a public health crisis. The Black Health Education Collaborative, or BHEC, is on a mission to fix it.

Co-led by family doctor and University of Toronto professor Dr. Onye Nnorom, Dr. OmiSoore Dryden, chair in Black Canadian studies at Dalhousie University, and Sume Ndumbe-Eyoh, an assistant professor at U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, BHEC is a community of six prominent Black Canadian health scholars and clinicians. They’ve set out to improve Black health through targeted education and research, and by taking on anti-Black racism and the interlocking systems that affect the health and well-being of Black communities across Canada.

To get there, BHEC has some ambitious initiatives. They include amplifying Black community voices to tell stories about accessing health care; creating a virtual platform for health care professionals and educators; championing education on anti-Black racism and Black health for clinicians; and developing educational resources to teach students, faculty and clinicians about racially just practices.

Already, their work has led to the meaningful inclusion of education about anti-Black racism and Black health information in Canadian journals and conferences. Next year, BHEC will launch learning modules designed to educate medical students, faculty and practitioners.

“Our focus is on transforming medical and health professional education curriculum,” Ndumebe-Eyoh says, “to ensure that Black patients and communities receive care that is respectful, safe and relevant across the health system.”—C.F.

Dr. Angela Cheung

For helping COVID long haulers

Months after falling ill with COVID, countless Canadians are still battling lingering symptoms, in what’s known as post-COVID condition (or, more colloquially, long COVID). That’s why Dr. Angela Cheung, a senior scientist at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute, along with Dr. Margaret Herridge, co-founded a longitudinal study called CANCOV to look at the short- and long-term outcomes of the illness.

An Ontario Science Table report from September conservatively estimates that up to 78,000 people had or are currently experiencing post-COVID condition in Ontario alone. The discoveries made by Cheung and the study’s investigators will be critical in helping long haulers understand and manage their symptoms. “Most of the attention has been on ways to keep people alive,” she told TVO earlier this year. “But now I’m hoping that … the attention will be on people with residual symptoms and trying to figure out what’s the best way to help them.”

Treatments like supplements and herbal therapies, medications used for post-viral syndromes, cognitive behavioural therapy and physical therapy are all being researched for their effectiveness. While it’s early, Cheung has reasons for optimism. “We are still trying to work out the optimal treatment,” she said. “But I do see patients getting better.”—A.Y.

Kyra Flaherty

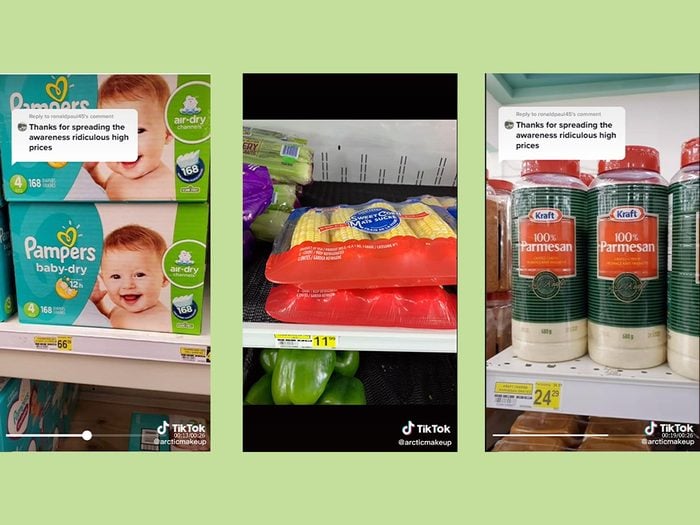

For exposing the staggering costs of living in Canada’s North

The inequalities of life in Nunavut are abundantly clear in the TikTok videos made by Kyra Flaherty: at one Rankin Inlet grocery store, a box of diapers is priced at $66, while a box of baby formula goes for $53.

The Iqaluit-based nursing student known as @arcticmakeup began posting videos near the end of 2020 that dispelled myths about living up north (like ubiquitous polar bears and igloos) and tracked the first COVID cases in the territory. But in 2021, after receiving questions in her comments about how much groceries cost, she began uploading TikToks of her trips to the grocery store. In one of the first videos of this series, she wrote that access to “affordable food is suicide prevention.”

Millions have seen her videos, and the attention from the media led to an outpouring of food donations from people moved to action by her TikToks. Flaherty distributes the food and essential items mailed to her throughout the community, and in early October, she announced a new project on TikTok: she launched a GoFundMe campaign to raise money for winter coats and boots to keep children warm in Nunavut.—K.B.

@arcticmakeup Reply to @ronaldpaul45 #greenscreen spreading awareness one community at a time #inuit #nunavut #arcticmakeup #inuittiktok #fyp ♬ original sound – creepy slowed audios

Dr. Vivian Stamatopoulos

For raising the alarm in long-term care

“I’m not one to stay quiet when I see bad things happening.” That’s what Dr. Vivian Stamatopoulos told Ontario’s commission into long-term care in March. The list of bad things happening in long-term care was long: families kept from their loved ones, residents being neglected, and a death rate from COVID-19 in Canadian LTC homes that far exceeded the international average.

When the pandemic began, Stamatopoulos, a professor at Ontario Tech University, was still grieving her grandmother, who’d recently died in long-term care. Stamatopoulos knew first-hand how families care for loved ones there. So she started speaking out. She gave at least 250 interviews to the press before she stopped counting.

And she got results. She helped secure the essential visitor policy for LTC homes, which recognized family members as providers of necessary care and granted them access to facilities. Her advocacy led to a vaccine mandate and the release of data about vaccination rates among staff and volunteers.

But her work won’t end with the pandemic. Long-term care is long overdue for an overhaul, says Stamatopoulos. National reform is “the only logical and safe path forward.”—C.F.

(Related: I’m Living in a Long-Term Care Home During Covid-19 — Here’s How I’m Coping)

Nikki Skillen

For fighting to secure nurses a fair wage

In May 2020, intensive care nurse Nikki Skillen started a Facebook group for nurses in Ontario to protest Bill 124, provincial legislation that limits wage increases for public sector workers. Firefighters and police officers were exempt from the bill, and Skillen, a 22-year veteran of public health care, wanted that same exemption extended to registered nurses, registered practical nurses and nurse practitioners. “Capped at 1 percent, nurses will earn less than inflation,” Skillen wrote—a ridiculously paltry amount for essential workers putting their lives at risk during a global pandemic.

Now called Ontario Nurses United and more than 20,000 members strong, the group helped nurses organize peaceful protests at MPP offices across the province. In 2021, Skillen’s advocacy work expanded to highlight issues such as burnout (60 percent of nurses reported high stress levels due to the pandemic), violence against nurses (which has increased over the past 20 months) and labour shortages (there have been more vacancies in nursing than in any other occupation). “We watch our peers suffer breakdowns while the responsibilities mount,” Skillen wrote. So in October, 300 nurses, doctors and health care staff marched in Toronto—her biggest rally in 2021. —A.Y.

Dawn Googoo

For helping Indigenous students in health care

Mi’kmaq registered nurse Dawn Googoo believes one way to advocate for the health of Indigenous peoples is to get them into the nursing profession. As the L’nu nurse initiative lead at Halifax’s Dalhousie University, she hopes to draw in more Indigenous people by offering students mentorship, emotional support and a culturally safe learning space.

During her time at St. Francis Xavier’s undergraduate nursing program, Googoo remembers the loneliness and anxiety she often experienced being the only Indigenous person in the classroom. “Each area of nursing discusses how Indigenous people are the lowest of the health disparities,” said Googoo in an interview with the CBC. “It’s brought up in every class. And there’s no history…. There’s no explaining.” Googoo would raise her hand to offer contextual insights, which was the kind of trauma-informed teaching missing from the curriculum. That’s why her new role includes collaborating with university staff to decolonize the program of study. One of her goals is to see at least one Indigenous nurse on campus at all nurse-training institutions across the country.

“We all have a right to relax, learn and work in a safe environment,” Googoo said in a welcome letter to new students. “Having a support system has brought me to where I am today.”—R.P.

Next, Meet Sisters Sage, an Indigenous Wellness Brand Reclaiming Smudging