Rolanda Ryan

For advocating for accessible abortions

As the owner and operator of Newfoundland and Labrador’s only abortion clinic, Rolanda Ryan and her team are crucial to ensuring reproductive rights and bodily autonomy in the province. She opened her St. John’s clinic, Athena Health Centre, in 2010.

Her clinic provides 90 percent of the abortions in the province, and you don’t need a doctor’s referral to access care. Athena’s practitioners also run a satellite clinic once a month, alternating between central Newfoundland and Corner Brook (a seven-hour drive away on the western coast), but access in other parts of the province (including all of Labrador) is still an issue. And while provincial health insurance covers the abortion procedure itself, travel, accommodations and associated expenses are not included.

To fill the gap, Athena offers telehealth counselling appointments and mails Mifegymiso (a pill that terminates pregnancies before nine weeks) all over the province. For terminations after 15 weeks, patients must leave Newfoundland and Labrador, as hospitals in the province don’t have the resources or training to provide this kind of care, Ryan explains. Ryan, who is 55, says keeping the clinic afloat during COVID shutdowns was tough—abortions dropped and Athena almost closed—until she advocated to change the provincial funding model and ensure they could keep their doors open.

In 2015 and 2016, Ryan’s advocacy work took her to the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador, and protesters were banned from congregating within 40 metres of abortion providers and patients. She is also one of two Canadian board members of the National Abortion Federation, a professional association for abortion providers south of the border, during a terrifying and turbulent time in the U.S. for reproductive rights. —Ariel Brewster

Related: The True Cost of an Abortion in Canada, According to an Expert

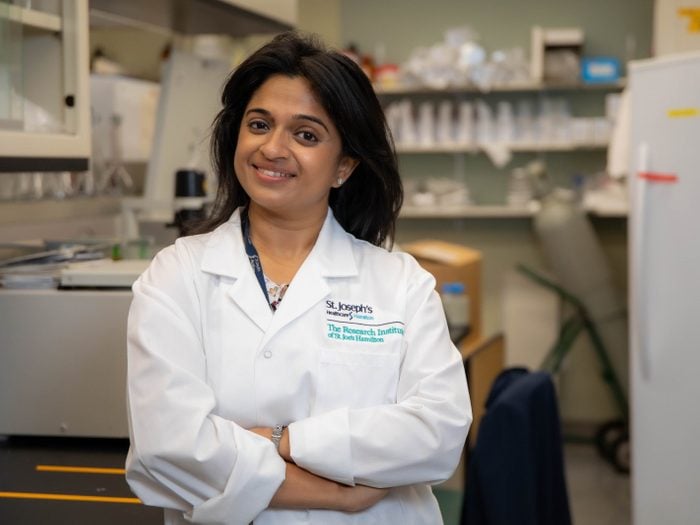

Manali Mukherjee

For connecting COVID to autoimmune diseases

Medical researchers have long identified a connection between viral infections and increased risk of autoimmune problems. Measles and mumps, for example, have been linked to the onset of type 1 diabetes, while a bout of mononucleosis (caused by the Epstein-Barr Virus) seems to slightly raise the risk of developing multiple sclerosis. So when COVID-19 hit, immunologist Dr. Manali Mukherjee wondered if it also triggered autoimmune responses, particularly in the 10 percent of people experiencing long-term symptoms that are shared with autoimmune diseases.

The McMaster University professor suspected that hyper-inflammation early in the infection produced rogue antibodies that persisted long after the illness’ onset. To test her hypothesis, she led a study that tested blood samples from 106 post-COVID patients, recruited between August 2020 and September 2021 at hospitals in Vancouver and Hamilton, and followed them for one year. Published this fall, the research identified two abnormal antibodies (autoantibodies) in up to 30 percent of patients a year after infection. “Just because you have autoantibodies doesn’t mean you have an autoimmune disease,” she cautions. “But we always consider that it might develop into an autoimmune disease.” For that reason, she advises anyone diagnosed with COVID symptoms lasting more than 12 months to get their autoantibodies tested, either through a GP or a rheumatologist.

Now, Mukherjee is leading a longitudinal research study that will follow 120 diagnosed long-haulers for more than a year, in part to answer the question of who develops autoimmune problems after COVID and why. The study will also look at whether the severity of long-haul COVID is related to autoimmune responses triggered by the virus and whether vaccination impacts the severity of long-haul COVID symptoms.

The answers to these questions are needed to both treat patients and manage healthcare systems. “The problem with long COVID,” says Mukherjee, “is the sheer number of people who have been affected and the magnitude of it.” —Caitlin Crawshaw

The Yarrow Intergenerational Society for Justice

For helping marginalized seniors access basic needs

On Monday and Friday mornings, seniors from Vancouver’s Chinatown and Downtown Eastside gather at a cultural centre to socialize and get their bodies moving. The gentle exercise class is put on by the Yarrow Intergenerational Society for Justice, which connects youth volunteers with low-income immigrant seniors. After the class, they chat over snacks from a local bakery and learn about other ways the society can support their well-being.

The loss of legacy Chinese-owned small businesses, the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes and pandemic lockdowns have all led to increased isolation for these seniors, many of whom don’t speak English as a first language. The staff and volunteers help them get to appointments and find community resources. They read and interpret government documents, help with subsidy applications and act as interpreters for scheduled medical appointments. They even provide culturally appropriate food through a grocery delivery program. All with the aim to help these seniors age in place, with dignified affordable housing and the community connection they desperately need. —Rebecca Philps

(Related: Why Doctors Should Be Versed in Linguistics and Sociology)

Gill Whelan

For launching a wellness resource for Newfoundlanders

Gill Whelan had been a fitness instructor for almost a decade when she took a hiatus in 2017. While the St. John’s-based coach was passionate about fitness, she was disillusioned by the toxic messages pervasive in the industry: “Often fitness is centered around making people feel like they need to change,” she explains.

When the world went into lockdown, Whelan saw how her family and friends were struggling to stay healthy and emotionally balanced. So, she created Whelan Wellness Virtual Bootcamp. For $52 a month, subscribers have access to daily workouts, yoga lessons, mental health discussions and workshops about mindful eating and nutrition. Within 24 hours of launching her four-week program, 121 people had signed up. At its peak, the virtual community reached 6,000.

Newfoundland’s many rural communities have long had limited access to wellness resources. The current shortage of health care workers makes it harder than ever to address concerns before they escalate into medical problems. While systemic issues still need to be addressed, Whelan is empowering people who want to take charge of their well-being. “It’s the most supportive group of like-minded individuals just wanting to feel better.”—Valerie Howes

Gift From the Heart

For offering dental care for those in need

6.8 million Canadians avoided seeing a dentist in 2018 because of the cost. Gift from the Heart (GFTH), an Ontario-based charity, is working to change that by offering free dental services to those in need. Their most recent endeavour had the group converting a church basement in Pincourt, Québec, into an oral hygiene clinic, offering free cleanings, assessments and fillings to migrant workers and Ukrainian refugees.

“The biggest thing lacking is access to care,” founder and president (and registered dental hygienist) Bev Woods said in an interview with CTV. That’s why GFTH has spent the past two years mobilizing two ambulances that have been retrofitted with dental equipment to function as preventative outreach vehicles, or clinics on wheels. Woods and GFTH Vice President Laura Iorio have personally driven the clinics across Ontario and Quebec to bring oral health care to more Canadians. “There is no health without oral health,” says Woods.

Since 2008, they’ve also been partnering with independent dental hygiene offices across the country, who dedicate full days to providing no-cost services to clients who otherwise wouldn’t be able to access the care. So far, the charity has provided $1.7 million dollars worth of services via a team of 2,500 dental hygienists. Now, GFTH is going bigger—with an enclosed trailer that’s currently being renovated and will provide more space for the organization to carry out procedures like emergency extractions and X-rays. It’ll be wheelchair accessible and is scheduled to be complete by the end of this year.—Arisa Valyear

Dodie Jordaan

For providing a safe haven for at-risk Indigenous women in Winnipeg

Dodie Jordaan is the executive director of Ka Ni Kanichihk, a non-profit that runs Velma’s House, Winnipeg’s only no-questions-asked shelter for Indigenous women at risk of sexual violence. “Winnipeg is seen as Ground Zero for murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls, and the Two Spirit community,” says Jordaan. “We were the only major [Canadian] city without a 24/7 safe space for women and the gender diverse community.”

Velma’s House opened in 2021, and in October 2022, $6.9 million in federal funding was announced to expand their facilities and deepen their programming.

“We allow people to come in wherever they’re at in life,” says Jordaan. “We have people who are doing survival sex work, or leaving violent, intimate-partner relationships.” Many women who come to Velma’s House don’t meet the criteria at traditional shelters because they have their kids with them or they’re struggling with substance use disorder.

In addition to providing food and shelter, Velma’s House also connects clients to services offered by Ka Ni Kanichihk, including counselling, a health clinic, addiction care and job training. They operate on an Indigenous model of care, which includes a 10-week healing program and access to elders and knowledge keepers. The federal funding will increase the number of beds from 10 to 60, and open more spaces in the Ka Ni Kanichihk daycare.

“Indigenous people, especially Indigenous women, don’t access health care as much as they need to, because of colonization, racism and fear of the medical system.” But at Ka Ni Kanichihk, says Jordaan, “you see nurses, and you’re also greeted by aunties and elders.” Having basic needs is about more than physical health, she says. It’s also about self-worth. “Having a place where you can heal, where you’re not being judged—is a step toward additional goals.”—A.B.

Janet Matheson

For caring for sexual assault survivors, and defending the nurses who treat them

“You’re seeing people on the worst day of their life. You want to be everything for that person—medically, emotionally, socially.” That’s how ER nurse Janet Matheson describes her mission as a sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE). So she was surprised when New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs disparaged SANE nurses for their “lack of compassion.”

In August, a woman went to Dr. Everett Chalmers Regional Hospital in Fredericton after being sexually assaulted. No SANE nurse was on call that night—at the time, there were five in the city, and between them Matheson estimates that they provided 90 percent of round-the-clock coverage. The patient says she was told to return the next morning when a nurse could examine her.

While Matheson was eventually called to perform the exam, the patient was understandably distraught and went public with her story. The premier and the provincial health authority were quick to blame the service. Their comments were “a slap in the face” to Matheson, who’s been with the hospital’s SANE program since its inception. “No one felt worse than we did,” says Matheson.

But, as she wrote in a Facebook post, what happened “was the fault of a system failing under its own weight because of the government’s inability to fix it.” In other words, the nursing crisis. There are about 1,000 vacant nursing jobs in the province, and after Higgs’s comments, four New Brunswick SANE practitioners resigned. But Matheson, who has worked as a nurse for 45 years, is optimistic. “I hope some good will come out of this and the SANE program will flourish.” —Caitlin Walsh Miller

Taylor Lindsay-Noel

For making the world a more accessible place

For many people, dining at a restaurant, going shopping or staying at a hotel isn’t as welcoming of an experience as it should be: Stairs, narrow passages and tiny bathrooms are physical barriers.

Taylor Lindsay-Noel, 29, who has used a wheelchair since she was 14, found that many businesses that claim to be wheelchair accessible actually aren’t. So she decided to document it all—the good and the bad—with accessibility reviews on TikTok under the username @accessbytay. “I want to show what happens when places have an inviting environment,” says Lindsay-Noel. “You get to see people like me out, having fun, being a part of society.” Through her 37,000 followers and 170 and counting videos, she certainly achieves that.

“My followers aren’t only people in wheelchairs, but also people who want to help elderly grandparents, people who’ve gotten injured or new moms who’ve never experienced looking for an elevator instead of a flight of stairs,” says Lindsay-Noel. “Sometimes the anxiety around figuring out if we can go is a barrier itself.”

She hopes her videos will encourage businesses to step up and people to speak out. “Be an advocate,” says Lindsay-Noel. We all deserve to feel welcomed wherever we go. —Renée Reardin

(Related: These Beauty Brands Are Designing Their Products With Accessibility in Mind)

National Safer Supply Community of Practice

For providing safer opioid drug supply programs across Canada

There are about 15 opioid-related-poisoning hospitalizations a day in Canada, and between January 2016 and March of 2022, there have been almost 31,000 apparent opioid toxicity deaths. Most of these deaths and hospitalizations are caused by illegal drugs contaminated with fentanyl, a toxic pain reliever that has a high risk of accidental overdose. One prevention group, the National Safer Supply Community of Practice (NSS-CoP), is working to scale up safer supply programs across Canada. Through webinars, social media outreach and mentorship, NSS-CoP works with public health units and advocacy groups to develop more robust safer supply programs. To prevent overdoses, these programs provide people with opioid addictions with legal pharmaceutical-grade drugs. With funding from Health Canada, NSS-CoP works with local initiatives in urban, rural and remote settings to create innovative models for providing safer supply. One recent example is a pilot program that launched earlier this year in Thunder Bay, Ont., a community where, in 2021, one person died of an accidental overdose nearly every three days. The program offers lessons in basic first aid, help filling out applications for housing or social assistance and ways to navigate the justice system. New measures like these connect people with the support systems they need to stay safe—one important tool in an ongoing response to Canada’s overdose crisis. —Rebecca Gao

Tabassum Wyne

For advocating for better treatment of Muslims in health care

As the founder and executive director of the Muslim Advisory Council of Canada (MACC), Tabassum Wyne is well-acquainted with inequities in education, employment policies and especially health care. Through surveys, the MACC has collected data on how Islamophobia in health care impacts practitioners, patients and caregivers.

Muslim women and girls seeking health care can be particularly affected. When Wyne gave birth six years ago, she experienced Islamophobia. This led her to become involved in the Family Advisory Council at McMaster Children’s Hospital, where she advocates for policy improvements to address these inequities. Wyne and MACC have also developed an “Islamophobia in Healthcare” training module that will launch in 2023.

In December 2021, when the Canadian Medical Association Journal published an article calling the hijab an “instrument of oppression,” Wyne met with CMAJ’s editor-in-chief to explain their concerns and advocate for its retraction. The journal took down the article and Wyne now serves as an advisor to the editor-in-chief.

If more health care organizations collected race-based data, it would create accountability when patients and staff report issues of racism. “There is a gap in Canadian society in understanding Islamophobia in health care,” says Wyne. “And we hope to be the organization that fills that gap.” —Zeahaa Rehman