Fruit Share Manitoba

It’s a warm summer evening in Winnipeg, and two women are deep into the branches of a sour Evans cherry tree. Perched on stepladders, they reach up, plucking off the ripe, plump, picture-perfect red fruit. Even though it is not their tree, they pick for several hours, sharing stories and swapping recipes to use the fruit.

The property owner, Wendy Barker, has welcomed them into her yard. She comes out from the kitchen with glasses of cold homemade cherry juice, squeezed from a previous glean. “This year produced a bumper crop,” she says. “We have more cherries than we can use or give away. There are even too many for the birds.” Refreshed after a long stretch of picking, the volunteers leave with buckets of fruit and the satisfaction of knowing the impressive yield won’t go to waste.

The pick was organized by Fruit Share Manitoba, one of many hyper-local urban harvest programs cropping up across Canada. The formula is very simple and often works as follows: Homeowners with unwanted fruit growing on their property connect to a local harvesting organization, which sends out a group of volunteer pickers. The harvest is divided up, usually into three: for the homeowner, the volunteers and a community organization in need.

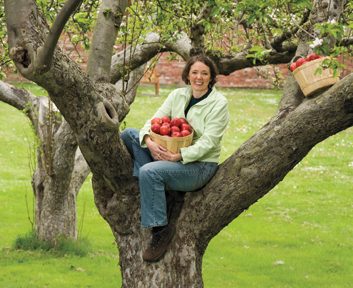

Fruit Share founder Getty Stewart (pictured) is a self-described “instigator and initiator.” Educated as a home economist, she has worked in team building and proposal writing. But her passion is fruit. She loves growing it, picking it and eating it. So a few years ago, when the 44-year-old mother of two saw bags and bags of ripe apples packaged up curbside on a street near hers waiting for garbage collectors, she was incensed.

“I thought, how can we be letting all of this nutritious, delicious, free fruit go to waste?” she recalls, particularly when almost 900,000 Canadians rely on food banks every month. She knew she had to do something about it. She founded Fruit Share in 2010.

Not Far From the Tree

In Toronto, two years earlier, Laura Reinsborough was volunteering with a non-profit group setting up a new farmers’ market. Organizers asked her to pick heritage fruit from the grounds of a downtown museum to sell. Reinsborough holds a degree in community arts through environmental studies and she grew up in Sackville, N.B., where there are plenty of fruit trees. But she had never picked fruit from a tree before. In fact, on the eve of that first pick, she watched YouTube demonstrations. The experience was eye-opening. “People were coming up and sharing stories of their fruit trees,” says the now 30-year-old mom of one, with another on the way. “Then I started to see these trees around the city I had never noticed before -apricots, cherries, apples. Meanwhile I was going out of my way to get local fruit from stores.”

Like Stewart, she, too, felt she had to act, and so she started Not Far From The Tree (NFFTT) in 2008. It now has 1,500 registered volunteers vying for an opportunity to pick city-grown fruit in their neighbours’ backyards.

Image: Thinkstock

LifeCycles Fruit Tree Project

There are like-minded people right across North America, but such “gleaning projects”-which attract both men and women volunteers-may well have started in Victoria in 1998 with the launch of what is believed to be the first urban harvest program on this continent. Renate Nahser-Ringer (pictured), 54, is manager of LifeCycles Fruit Tree Project. She says there is a huge abundance of fruit in Victoria thanks to a legacy of orchards dating back to the 1800s. One of the first picks she participated in was in 2004, when four people harvested almost 275 kilograms of pears from one backyard. “I had no idea it was possible to have that much fruit on one tree,” she recalls thinking. “This fruit would have fallen to the ground, rotted, and fed the rats.” Instead, it was shared with the tree owners and volunteer pickers, and also became nourishment for food banks, soup kitchens, shelters and many community centres.

Image: Gary McKinstry

Fruit shares across Canada

Within a year, Vancouver had adopted the concept. Like dandelion seeds, the idea spread and sprouted through Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario. Plans for such projects have been germinating in Montreal and Halifax as well. At least a dozen gleaning projects are currently in place, with a reported collection of almost 32,000 kilograms of free food last year alone. That’s a lot of apples, raspberries, cherries, peaches, pears and more.

Almost all of these initiatives are headed or were founded by women with an interest primarily in food but also the environment. Some hold part-time seasonal staff positions, funded through grants and donations; others are strictly volunteer. Stewart has written the popular Prairie Fruit Cookbook. When Amy Beaith-Johnson, 35, is not in full seasonal swing as director of Operation Fruit Rescue Edmonton, she works on her business making handcrafted soaps and skin products. Hidden Harvest Ottawa co-founder Katrina Siks, 32, works with Outward Bound for most of the year, teaching dogsledding, among other skills. Nahser-Ringer is a nurse.

Image: Thinkstock

What makes fruit shares a success?

The response to their efforts has been tremendous, with plenty of people very happy to let the juices flow down their arms even on hot summer days. In Hamilton, Ont., Juby Lee isn’t surprised. “The concept is so simple,” says the 34-year-old project coordinator of Environment Hamilton’s Fruit Tree Project. “People really get it. Harvesting fulfills people’s desire to help and offers a very tangible volunteer experience.”

The generosity of homeowners is not lost on her, either. “In this time of liability, when people could say, ‘Stay off my property,’ it’s a very sweet relationship,” she says. The tree owners fall into several categories. Some have purchased homes not realizing the beautiful spring blossoms would result in bushels of crabapples a few months later-and don’t have either the time or the inclination to pick the fruit and make, say, crabapple jelly. Others don’t like the mess of rotting fruit and the inevitable wasps. And there are many who love their trees and have enjoyed the bounty but, with age, are no longer able to harvest or eat all the fruit. Whatever the reason, homeowners are thrilled to have the heavy lifting done by someone else, and to know they have made a contribution to those in need.

Where generations past have honoured the backyard orchard and treated it as part of their pantry, urban dwellers have become increasingly reliant on grocery stores for all of our food supplies. Ottawa’s Siks sees a loss of connection with the food around us. “Some of us seem to be more reassured by food that comes from a package rather than food in our neighbourhood,” she says.

Image: Thinkstock

Re-learning how to use local produce

The truth is, many of us have forgotten how to use some local produce. Fruit from the ginkgo tree, for instance, is not on many household menus. Siks admits it does have a strong, unpleasant odour. “But the nut inside is a delicacy in some countries. You roast the nut in the oven and it’s delicious.” Toronto’s Reinsborough has become enamoured with sumac, a leafy shrub with fuzzy red berries (but there is a type of sumac that is poisonous, so be sure you know what you’re dealing with). “We rarely pick it, because few homeowners realize it’s edible,” she says, but it makes a lovely tea-and through a partnership with a local brewery, NFFTT is able to make beer from it.

Image: Thinkstock

How fruit shares help

Of course, the most gratifying partnerships are with the community agencies that welcome the free produce, and that sometimes even help with the work. When Jaki Skye saw a poster for Winnipeg’s Fruit Share, she contacted Stewart immediately. As health and wellness program coordinator at the city’s North End Women’s Centre, Skye saw valuable opportunities for the two organizations to work together. The centre offers support and resources for women in need, most of them low income. The fruit that comes through its doors from Fruit Share is filling baskets that would otherwise be empty. Skye says it’s handed to women to eat fresh or take home to their families. It is also used for workshops on cooking and drying, and is included in weekly lunch menus. Skye explains: “A lot of times women in our community have grown up without proper mothering or parenting, so they may have a limited diet.” It would appear that, sometimes, eating freshly made applesauce can be as new and transformative an experience as picking an apple was for Laura Reinsborough.

Strangers meeting in the branches of a tree have made a difference. “It’s a wonderful, practical, common-sense kind of thing,” Skye says, “and it really works in a good way.”

Image: Thinkstock

Related:

• 8 herbal teas you can grow in your garden

• Canada’s community gardens

• 5 must-visit farmers’ markets in Canada