Nori is the Japanese word for dried edible seaweed, and it’s been consumed for thousands of years. Nori was eaten as a thick paste until the 1700s, when the Japanese developed a way to dry it in sheets, applying the same method they used to make writing paper.

Today, nori is made from strands of edible red algae that are shredded, pressed into ultra-thin sheets and then dried and toasted. Baking at a low temperature dehydrates the seaweed, while roasting enhances its briny flavour. The best algae for making nori grows in cold, nitrogen-rich water and is cultivated in both the northern and southern hemispheres.

Nori is often associated with Japanese cuisine, but it’s also long been a popular item in Scotland, where the unpolluted, cool waters along the coast offer ideal growing conditions. The Scottish regularly use the mineral-rich seaweed as fertilizer but have also traditionally included it in their diet in dishes like oatmeal.

(Related: Chlorella vs. Spirulina: Which One Is Right for You?)

Why it’s good for you

The algae used to make nori is a true superfood. Algae contains up to 50 percent protein by dry weight and all nine amino acids, which puts it on par with other vegetarian protein sources like tofu and eggs. Why is this sea plant so protein-packed? It’s all thanks to photosynthesis, the process by which algae converts sunlight into energy. This ability to produce its own food, coupled with algae’s naturally high growth rate, generates more protein than other plants.

Seaweed is also often touted for its high mineral content, which is 10 times greater than that of plants grown in soil. This is due to the large concentration of minerals in seawater, which makes dried nori a good source of micronutrients like vitamins A and C, iron and iodine. Iodine is a mineral that’s important for a well-functioning thyroid, a gland responsible for regulating metabolism, and reduced levels can lead to hypothyroidism. Maintaining healthy iodine levels has also been shown to stimulate immunity and may help mitigate symptoms of fibrocystic breast disease.

Ever wonder where fatty fish, like salmon, get their omega-3 content from? It turns out the origin is their algae-heavy diet. Nori is a source of polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as DHA and EPA, two important fatty acids the body is not able to produce itself. Polyunsaturated fatty acids from algae are well-absorbed by humans and are cardioprotective, helping to lower blood lipids and improve cholesterol levels.

(Related: Should You be Drinking Chlorophyll Water?)

How to use it

Another great thing about nori is that it’s readily available in most grocery stores, in the international aisle. When buying nori, look for sheets that are dark green, smooth and uniform in texture, and avoid those with splotches or a reddish tint. Try Eden Foods Toasted Nori Sheets ($10, houseofwellness.ca). You can also find smaller sheets in snack-size packages for a quick salty bite.

To keep nori in top form, store it in airtight packaging, and if you won’t get to it within two weeks, pop it in the freezer, where it’ll maintain its freshness for about six months.

You may not be up for rolling your own sushi, but there are many equally delicious ways to use nori that require less time and effort. Nori imparts dishes with the same savoury flavour as bacon or anchovies, courtesy of one of the amino acids it contains: glutamate, the same compound used in MSG. Harness that umami in your cooking by incorporating nori into seasonings, dips and noodle dishes or using it as a garnish for soups and stir-fries. In Japan, ground-up nori is made into an all-purpose topper called furikake, a blend of seaweed, sesame seeds and other seasonings that’s excellent sprinkled on rice and eggs.

Now that you know the health benefits of nori, this is what you need to know about romanesco.

Over the past decade, shade selections for beauty products have expanded. A diverse range of models are being represented in campaigns and overly retouched advertisements are no longer the norm. But despite the beauty industry’s efforts to become more inclusive, people with disabilities have largely been left out—until now. Independent cosmetics companies and big-name brands alike are finally prioritizing intuitive, user-friendly packaging that serves beauty lovers with disabilities.

Last fall, Olay piloted an easy-to-open lid prototype—a chunky cap with winged handles that fits all Olay moisturizers. The modular, grippy design allows people with dexterity issues or limb differences to effortlessly remove the lid with one hand, while a high-contrast label and Braille lettering help those with visual impairments distinguish each product. This move is in line with its parent company Procter & Gamble’s broader 2020 pledge to make all of its packaging more accessible by 2025. It’s a shift that started in 2018 when Herbal Essences—one of more than 65 companies in the P&G family—added raised bumps and stripes (known as tactile markers) to their shampoo and conditioner bottles for those who are visually impaired. Procter & Gamble made the design for Olay’s easy-open lid open-source, meaning that other brands can copy and refine the features, allowing the beauty industry to work collectively towards identifying and removing barriers.

The push for more accessible products can be partially credited to P&G’s accessibility leader, Sam Latif, who is blind. In her two decades with the company, Latif has hired more people with disabilities and spoken to consumers with disabilities about their frustrations. Unfortunately, Olay’s caps are only available in North America, proving that we still have further to go when it comes to making accessible products readily available.

In Canada, one in five people over the age of 15 has a disability. For those with visual impairments, beauty packaging with raised bumps, high-contrast colour schemes and easy-to-decipher fonts can make a big difference. “These are things that are so simple and minute, but that most companies just haven’t thought of,” says Mary Mammoliti, a Toronto-based food expert and disability advocate who is legally blind.

Mammoliti was diagnosed in her 20s with retinitis pigmentosa (a degenerative eye disease) and had to adapt her beauty routine, relying more heavily on her senses of touch and smell to find products that work for her. Today, she actively seeks out brands like U.K.-based Blind Beauty, which emphasizes product scent, texture and accessible packaging with its vegan and cruelty-free skin care products. Other companies like U.S.-based Victorialand Beauty specialize in packaging that features the CyR.U.S. System (raised universal symbols) and embossed QR codes that play audio information about the products within its certified organic skin care line.

Not all accessible brands shout their merits from the rooftops—in fact, one of the most ubiquitous beauty tools is actually an innovator in inclusive design. Peer into any makeup artist’s cosmetic bag and you’ll likely find a Beautyblender ($26), a teardrop-shaped sponge made for streak-free makeup application that was designed by co-founder Veronica Lorenz, who has dexterity issues. After being diagnosed with a benign cervical spinal cord tumour in the 1990s that left her with reduced feeling in her right hand and arm, the Vancouver-born, Los Angeles-based former makeup artist had to hold tools and brushes with her non-dominant hand. The Beautyblender’s foam construction allows users to apply foundation in a natural-looking way, but it also boasts a chubby shape that is easier to grip than your typical makeup brushes.

Lorenz says the product wasn’t marketed as a tool for people with disabilities out of fear that it wouldn’t be widely accepted. At the time of the Beautyblender’s launch in 2007, many brands avoided the topic of disabilities completely. Lorenz says she is now seeing this change, especially as more people realize that self-care routines can be especially empowering for people living with chronic conditions and disabilities. Her own journey has led her to continue to design several products specifically for people with disabilities, including VampStamp, a tool with a winged eyeliner stamp on the end that can be dipped in ink and easily pressed along the lash line. The product became a go-to for people with dexterity issues, as well as anyone with less-than-perfect application skills.

Today, more products are taking an inclusive approach. Kohl Kreatives has a line of flexible makeup brushes (£45) that bend forwards and backwards, allowing users (including those with motor disabilities) to apply makeup in a way that’s comfortable for them. Other products require only one hand to use, like Revlon’s One Step Hair Dryer and Volumizer—a round brush and hair dryer in one—and Drunk Elephant’s Protini Polypeptide Firming Moisturizer ($89), which has a push applicator that eliminates the need to squeeze or tilt the bottle to dispense the product.

But much of the work left to be done goes beyond creating inclusive products. It’s also about encouraging the beauty industry to allow people with disabilities to tell their own stories, says Xian Horn, a New York City-based beauty and disability advocate. “We’re combating old-fashioned ideas around what disability looks like, feels like and is like,” she says. “The more empowering stories that we can share, the more of a ripple effect it will have on future generations.”

Try these accessible beauty products in Canada:

Love how your stylist blows out your ‘do? You can DIY the look with the help of this twofer—with just one hand. It’s a hairbrush and hair dryer in one and can provide uber volume, bounce and curl to your mane.

Revlon One Step Hair Dryer and Volumizer, $70, bedbathandbeyond.ca

While Lorenz’s iconic VampStamp shop is on hiatus (the pandemic had a negative effect on her company, but she hopes to relaunch soon), Kaja’s version makes a convenient replacement. The stamp allows you to press on a perfect flick, while the pen can be used to line lashes for a complete cat-eye look.

Kaja Wink Stamp Wing Eyeliner Stamp & Pen, $38, sephora.com

Victorialand skin care products—like the brand’s moisturizer, face oil and sleep mask—deliver deep hydration and luminosity to the skin. But the perks don’t stop there: the packaging offers functionality to people with vision impairments, as it boasts a CyR.U.S. symbol, which is a raised universal identifier.

Skin-Loving Moisturizer, $62, victorialandbeauty.com; Skin-Loving Sleep Mask, $76, victorialandbeauty.com

Boasting a bendy feel and wobbly shape, these makeup brushes are easier to both grip and use than the standard variety, making them a particularly great option for someone with a motor disability or disease. What’s more, the tips come in a variety of shapes—triangle, square and diamond—to make it easier to slip into the nooks and crannies around the nose and eyes.

Kohl Kreatives The Flex Collection Brushes, £45, kohlkreatives.com

This commendable bottle requires just one hand to access the good stuff. A built-in pump at the top allows you to get just the right amount of product on your fingertips that can then be rubbed onto your face to boost skin tone and texture.

Drunk Elephant Protini Polypeptide Firming Moisturizer, $89, sephora.com

With its plump shape and pointed tip, the Beautyblender allows users to apply foundation and achieve a natural-looking finish that—unlike makeup brushes—doesn’t require a strong grip or precise application to use.

Beautyblender Original Makeup Sponge, $26, sephora.com

Next: 5 Canadians with Disabilities on the Upsides of Working from Home

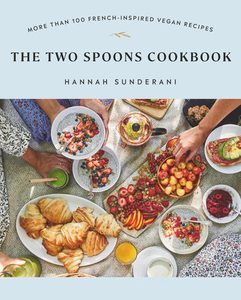

This faux gras is made from mushrooms and lentils and well-seasoned for an umami-rich spread that is very similar in taste to pâté.

Foie gras is really popular in France, and when living there I discovered a tasty plant-based version at a small vegan shop called Végétal & Vous. Back home in Canada, my homemade version has become the perfect replacement for the little tin of faux gras that I used to buy in Lille. The best way to enjoy it, in my opinion, is generously spread on toasted garlic bread.

Faux Gras

Makes about 2 cups

Ingredients

Faux gras

- Heaping ½ cup dried French green lentils (du Puy lentils)

- 2 tablespoons coconut oil

- 2 cloves garlic, finely chopped 1 shallot, finely chopped

- 8 ounces (225 g) white button mushrooms, chopped

- 2 teaspoons chopped fresh rosemary 2 teaspoons fresh thyme leaves

- ½ cup raw walnuts

- 2 tablespoons nutritional yeast 2 tablespoons lemon juice

- 1 tablespoon gluten-free tamari 1 teaspoon pure maple syrup

- 1 teaspoon tomato paste

- ¾ teaspoon dried cilantro

- ¼ teaspoon cinnamon

- ⅛ teaspoon ground cloves

- ½ teaspoon fine sea salt

- Pinch of freshly ground black pepper

Garlicky Bread

- 1 baguette, cut into 1-inch-thick slices 2 cloves garlic, halved lengthwise

- 2 to 3 tablespoons vegan butter

- 1 cup arugula, for topping (optional)

Directions:

- Make the Faux Gras: In a medium saucepan, combine the lentils and 4 cups of water. Bring to a boil over high heat, then reduce heat to medium-low and simmer until the lentils are soft, about 20 minutes. Drain and set aside.

- Heat the coconut oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Add the garlic and shallot and cook, stirring frequently, until softened, about 7 minutes. Increase the heat to medium-high. Add the mushrooms and cook, stirring occasionally, until softened and the juices from the mushrooms have mostly evaporated, about 10 minutes. Add the rosemary and thyme and cook until fragrant, another 3 to 4 minutes.

- Scrape the mushroom medley into a food processor. Add the lentils, walnuts, nutritional yeast, lemon juice, tamari, maple syrup, tomato paste, cilantro, cinnamon, cloves, salt, and pepper. Pulse until well combined and smooth. Transfer to 2 small jars. Serve or chill for later. Serve topped with a few arugula greens, if desired.

- When Ready to Serve, Make the Garlicky Bread: Set the oven to broil. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper. Rub one side of each slice of baguette with cut side of garlic, then butter each slice. Lay the bread on the prepared baking sheet and toast under the broiler for 2 to 3 minutes, until golden brown and crisp. Serve baguette slices alongside the faux gras for slathering.

Storage: Store the faux gras in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to 5 days or in the freezer for up to 3 months. If frozen, thaw in the refrigerator the day before using.

Excerpted from The Two Spoons Cookbook, by Hannah Sunderani © 2022, Hannah Sunderani. Photography by Hannah Sunderani. Published by Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: This Vegan Sloppy Joe Dish Makes a Healthy Comfort Food

I was eight years old, sitting at the dinner table with my family, when my grandmother slipped her arm around me and pressed her knuckle straight into the small of my back. I jolted upright—exactly as she intended. It would be the first of many swift jabs whenever she’d catch me slouching. And it worked: I developed a habit, which lasted for years, of correcting my posture throughout the day, no knuckle necessary.

But then the pandemic came, and as life as we knew it fizzled away, so did my good posture. I was worried I’d developed a bit of a hunched stance and needed a new reminder to straighten up. And that’s when I scrolled upon Upright’s posture training device.

The 3.8-centimetre gadget, which can be worn as a necklace or stuck on your back with disposable adhesives, has a sensor that can detect a slouch. It links to your phone to track your posture via the brand’s app; a little graphic mimics your body’s position, so when you hunch you’ll see a slanted figure. Hunch too far, and the device on your back vibrates as a gentle reprimand—not unlike an electric fence that gives disobedient dogs a little shock.

Sitting at my desk, I stuck the device onto my back, set the timer on the app for 60 minutes and assumed a regal stance. My goal was never to let the device vibrate. So when I had a hard time reading a document on my computer, I didn’t lean forward; I moved my screen closer. When I had to grab something off the ground, I didn’t stoop down; I lowered myself via plié. On the few occasions when I forgot about the device and was vibrated back into compliance, I felt like a scolded dog and retreated into a frozen position.

Each day, I increased my goal on the Upright device, hoping I’d soon default to good posture. While the device was certainly an effective reminder, I wondered if it was enough. What about the other elements it wasn’t able to track, like my squared shoulders and my alignment?

“When aiming for perfect posture, the back is actually the least important body part to focus on,” says Dr. Liza Egbogah, a Toronto-based osteopath and chiropractor. Instead, she says I should focus on my front, since tightness there causes the body to pull forward into a croissant shape.

With her clients, Egbogah uses massage techniques to loosen their chest, fascia around the neck, pec muscles and hip flexors, making it easier for them to pull their shoulders back, sit up straighter and maintain that pose, as well as to reduce body aches. “When your body is out of alignment, there’s going to be an impact on your joints,” she says. This can lead to faster degeneration of joints, causing pain and even early-onset arthritis.

A tool like the Upright device can be beneficial, Egbogah says, as long as it’s treated as a posture reminder, not a corrector. That means before using it, Egbogah recommends understanding what “good posture” means: ears in line with shoulders, shoulders in line with hip bones and hip bones in line with the outer parts of the ankles. Then, ease tightness in the body by using a lacrosse ball or foam roller.

Performing short, simple stretches throughout the day is also key for addressing tightness. Egbogah says that when she sits at her desk, she simply pulls back her shoulders every hour or so. When standing in line at a store, she crosses her arms behind her back to open her chest.

Once your body’s loosened up, Egbogah suggests going slow with the Upright device; like building up muscle, improving posture takes time. She recommends using it for just one or two hours a day, preferably in the afternoon, when muscles have likely fatigued.

On the days I use the posture corrector and stretch my body, I find it’s less work to keep my back straight. The more I use my foam roller, the easier it is to keep my body in alignment. And the more attention I pay to my posture, the better I feel. I knew good posture was an easy confidence booster, but I was surprised to learn it’s a mood booster, too: Studies have shown it can decrease stress, anxiety and depression.

Recently, my boyfriend commented on my excellent posture and told me I looked taller. “Maybe I should get this thing,” he said, gesturing to the Upright. “No need,” I told him, pressing my knuckle into his back. “I got you covered.”

Next: 5 Strength-Training Moves for Your Best-Ever Posture

A ginger bug is like a sourdough starter. It’s fed daily, and using a little kick-starts the fermentation process for the beer.

Homemade ginger beer is spicy and not too sweet, especially this version, sweetened largely with apple juice. I’ve tried with honey but it doesn’t produce consistent results. If you like carbonated drinks, this is like a healthier soda pop and great to add to a number of drinks and cocktails. Ginger beer is probably the easiest thing to ferment at home.

Ginger beer and bug

Makes 2 pints (1 litre)

10 minutes prep time, 15 minutes cooking time, 5 days (ginger bug) plus 3 to 10 days (ginger beer) fermenting time

Ingredients

Ginger Bug, for Each Feeding

- 1 teaspoon finely grated fresh ginger

- 1 teaspoon cane sugar

- 3 teaspoons water

Ginger Beer

- 3 cups (750 ml) water

- 1 large piece ginger (about 6 inches / 15 cm), sliced

- ¼ cup (60 ml) ginger bug

- Juice of 1 lemon

- 1 cup (250 ml) apple juice

Instructions

- To make the ginger bug, add the ginger, sugar, and water to a jam jar or container—the 8-ounce (250 ml) Ball jars are ideal—and stir to dissolve the sugar. Cover with a thin cloth and secure to keep any insects out.

- Feed your bug the same amounts of ginger, sugar, and water on a daily basis, and you should see strong bubbling action after about 5 days. Once it’s very bubbly, it’s ready to use for the ginger beer. Continue to feed daily if you want to make a batch of ginger beer about once a week. If you plan on making ginger beer less frequently, refrigerate the bug until you want to use it, then feed once and leave it on the counter to use the next day (see note).

- Sterilize a 2-pint (1 litre) bottle with a flip-top. You can use boiling water or run it through a dishwasher cycle.

- To make the ginger beer, add the water and ginger to a large pot and bring to a boil. Simmer, covered, for 10 to 15 minutes, or until it smells strongly of ginger and is pale yellow. Remove from the heat and cool, with the lid on, until room temperature.

- Pour the ginger tea into a large non-metal bowl with a spout or any other non-metal bowl. Pour the ginger bug through a fine strainer into the tea, add the lemon juice, and gently stir with a wooden spoon.

- Pour the apple juice into the clean bottle, then top with the ginger tea mixture. Seal and set in a dark place for 3 to 10 days (see note). The timing is a wide range because temperature will play a large role. Pop (or burp) the bottle once a day to release any pressure buildup. After the ginger beer is very fizzy, the bottle is ready to refrigerate and drink. Store in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks.

Notes:

A ginger bug can stay dormant in the refrigerator for months. The longest I’ve kept it is about 4 months; I then fed it once and it was back in action the next day. If you want to keep it for a while without using, cover it with a lid or something non-permeable.

If your house is very hot, try to find a cool place for the ginger beer when it’s fermenting. The summer I wrote this book, I had a few bottles on the counter and one exploded after less than 2 days, even though I had burped it earlier that day. It was a record-breaking summer for heat, over 105°F (40°C), and as I mentioned before, Dutch houses are not built for heat! I’ve read that some people store their bottles in bins so that any explosions don’t hurt anyone nearby.

Excerpted from Occasionally Eggs: Simple Vegetarian Recipes for Every Season by Alexandra Daum. Copyright © 2021 Alexandra Daum. Photography by Alexandra Daum. Published by Appetite by Random House®, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved

Next: Trying to Drink Less? These Tasty Summer Mocktails Make it Easy

There are a few foods I didn’t discover until later in life. Fennel was one of those foods, but now it finds its way onto my grocery list every week. The celebrated vegetable is delicious both raw and roasted, and its dried seeds are equally versatile.

Fennel is a generous plant. Its leaves, seeds and bulb are packed with flavour and good-for-you compounds. There are two main types of fennel: Herb and Florence fennel. Herb fennel’s light green leaves resemble dill and sprout pale yellow flowers in the summer. Once these flowers turn brown, they’re harvested and hung to dry and the seeds that fall from the flowers are collected. These seeds are the final product that show up in the spice aisle at the grocery store.

Florence fennel, on the other hand, is what you’ll find in the produce section or at the farmer’s market, and can be eaten raw or cooked. It’s shorter with darker green foliage, called fronds, and celery-like stalks that extend down to a large white bulb, which forms the base of the plant. Both types of fennel have a mild anise flavour that is reminiscent of a sweeter black licorice.

Florence fennel is low in carbohydrates and is a good source of fibre, vitamin C, beta carotene (which our bodies turn into vitamin A) and potassium. Fennel seeds, meanwhile, are one of the world’s oldest medicinal herbs, and are used to create remedies for colds, allergies and stomach pain. Tinctures, teas and supplements are made from dried fennel seeds that are crushed to release their healthful essential oil. Anethole and fenchone, aromatic compounds that are major components of the essential oil, have been shown to break up and clear phlegm in the respiratory tract, making them an effective treatment for congestion. These compounds also relieve bloating and gas.

Anethole and fenchone are also known as phytoestrogens—plant chemicals that are similar in structure to estrogen and can mimic its action in the body. For post-menopausal people they can help manage symptoms that result from a shift in estrogen levels, like hot flashes and insomnia. In those who are still menstruating, anethole and fenchone have an anti-inflammatory effect that can relieve symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, like cramps and heavy bleeding, reducing the need for over-the-counter painkillers. In those who are breastfeeding, the compounds can stimulate prolactin secretion, the hormone responsible for milk production, although further studies are needed to confirm this.

Fennel seeds are also incorporated into spice blends across the Middle East and Asia, including Chinese five spice and garam masala. They’re used to flavour sausages, chutneys and marinara sauce. In many cases, fennel seed adds that hard-to-pinpoint flavour that makes a dish distinctive. Toasting and crushing the seeds activates their aroma, which lends itself well to curries, stews, salad dressings and roasted vegetables. They pair particularly well with tomatoes and roasted cauliflower. Fennel seeds are green when fresh and slowly turn a dull grey-brown as they age, so for the most flavour seek out green seeds.

When eaten raw, fennel bulbs are best thinly shaved and added to a salad or slaw—its strong flavour goes a long way. Shaved fennel makes a great addition to salads with a sweet element, like in a slaw with apples or a salad with citrus or beets. The bulb’s core and stalks are tougher and fibrous, so it’s best to leave them out of raw dishes, but they soften up nicely when cooked.

While raw fennel has a satisfying crunch, it becomes silky and tender when cooked and takes on a sweeter taste, which pairs beautifully with pork, fish and other seafood. Try thinly slicing and adding it to pizza with Italian sausage, arranging larger pieces under a chicken before roasting so it caramelizes and soaks up the tasty juices, or baking it into a cheesy, breadcrumb-topped gratin instead of using potatoes.

You can find fennel seeds year-round and Florence fennel is in season from fall through spring, making it the perfect veg when other produce like tomatoes and zucchini are not yet at their peak. If you’re suffering from veggie fatigue, add a fennel-spiked meal to your weekly rotation.

Laura Jeha is a registered dietitian, nutrition counsellor and recipe developer. Find out more at ahealthyappetite.ca.

Next: A Summer Soup? Yes—Just Try This Roasted Fennel and Tomato One

Roasted Fennel & Tomato Soup with Dukkah

Makes 4 servings (2 litres total)

Prep time: 5 minutes

Cook time: 40 minutes

Total time: 45 minutes

Ingredients

Roasted fennel and tomato soup:

- 2 medium-sized fennel bulbs, ends and stalks trimmed, cut into eighths

- 1 pint cherry tomatoes

- 1 head of garlic, cut in half

- 1 onion, diced

- ¼ cup olive oil, divided

- 14 oz can whole plum tomatoes, chopped with juices

- 3 cups chicken or vegetable stock

- 1 tsp kosher salt, plus more to taste

- black pepper, to taste

- ¼ tsp red pepper flakes

Dukkah:

- ½ cup hazelnuts

- 3 tbsp sesame seeds

- 1 tbsp coriander seeds

- 1 tbsp cumin seeds

- 1 tbsp fennel seeds

- ½ tsp kosher salt

Directions

- To make the soup: Preheat oven to 400℉. Arrange sliced fennel, cherry tomatoes and garlic on a large baking sheet. Drizzle with 2 tbsp of olive oil and season with salt and pepper.

- Bake on middle rack of oven until vegetables are very soft and starting to caramelize, 35-40 minutes.

- Meanwhile, heat remaining 2 tbsp olive oil in a large pot over medium-low heat. Add the onions and cook, stirring often, until soft and translucent, 5-7 minutes. Add the canned tomatoes, stock and red pepper flakes and bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low and simmer, 10 minutes.

- Working in batches, add roasted vegetables and peeled garlic to a blender along with tomato-stock mixture. Season with 1 tsp kosher salt and blend well until smooth. Add more stock, if desired, to thin.

- To make the dukkah: Add the hazelnuts to a dry non-stick skillet over medium heat. Toast until fragrant, about 2 minutes, then add the rest of the seeds to the skillet and continue to toast until lightly golden, about 2-3 minutes more. Place nut and seed mixture in a small food processor or blender, and pulse a few times to break down the nuts and seeds, leaving some larger pieces intact. Use immediately or store in an airtight container for up to 2 weeks.

Tip: Keep leftover dukkah in the pantry and sprinkle it on dips, roasted vegetables, eggs, soft cheeses or on pita bread brushed with olive oil.

Next: Why You Should Add Fennel to Your Veggie Rotation

Not long ago, a small corner of TikTok rallied around the “One Trip Challenge,” where competitors carried as many overstuffed grocery bags as possible from one point to another. It didn’t exactly break the internet; it was a fun marketing stunt by a Greek yogurt brand hoping to draw a connection between their protein-packed product and feats of superhuman strength. But it was completely relatable: Who hasn’t stared into the trunk of a car at a heap of groceries and thought, Yeah, I can totally get this inside in one load?

Whether you actually can do it is determined by your grip strength—the same force that lets you hang on when your dog suddenly takes off after a squirrel, or climb up or down a ladder, or pull an outward-opening door on a windy day. Stirring a pot of risotto, opening a jar of pickles, hoisting up a toddler or tearing up an old bank statement: Whenever you do any of these things, you are engaging grip strength.

What is grip strength?

“In the simplest terms, grip strength covers your ability to close your hand,” says Mia Nikolajev, a strength and conditioning coach and trained firefighter. But more than that, “it indicates your ability to generate strength at the end of your limb, and it’s basically an indicator for muscular strength and tone.” Grip strength is shorthand for your overall fitness, and it’s why your doctor may also be interested in measuring it at your next physical exam: Multiple studies show that those with a stronger handgrip are also at lower risk of developing heart disease, diabetes and strokes.

One of the most convincing studies followed half a million participants over three and a half years to see if there was a correlation between grip strength, mortality and disease. Participants ranged in age from 40 to 69, and encompassed a range of ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, pre-existing conditions and lifestyle behaviours, like physical activity and diet—a pretty decent sampling of the general population. For both men and women, researchers found that a lower grip strength was associated with a higher risk of mortality in general, and a higher rate in particular of developing and dying from “cardiovascular disease, all respiratory disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, all cancer, and colorectal, lung and breast cancer.” Whew.

“We also know that muscular strength and endurance are pre-indicators of the potential for bone density loss, and specifically osteoporosis in women, who tend to be more prone to these conditions,” says Nikolajev. “If you tend to be stronger or have more muscle mass, muscle density and a habit of training or fitness, you’re less likely to incur non-hereditary disorders or illness.”

How do you measure it?

Grip strength is typically tested in a clinic using a hand dynamometer where you sit with your feet flat on the floor, arms held at right angles with the elbows tucked beside the body. Then, grasp the handle of the instrument, squeeze it for all you’re worth and hold for five seconds. Perhaps unsurprisingly, men aged 20-30 typically have the greatest strength, while women over 75 have the weakest. According to a study in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, the “mean grip strength ranged from 49.7 kg for the dominant hand of men 25 to 29 years of age to 18.7 kg for the non-dominant hand of women 75 to 79 years of age.”

Naturally, aging causes a decline in both muscle mass and function, and as it goes, so does grip strength. But there are a number of easy, at-home ways to build and maintain it, so you can button your pants well into your 90s (because, yup, pants-buttoning requires grip strength too).

How to improve grip strength

Nikolajev tells her clients to put a couple of milk cartons, or free weights, in a tote bag and just hold it for 20 to 30 seconds, then build duration from there. “You could go for a walk around your home, or even just march in place. You’re trying to create instability and force your hand to do a little bit more work.”

You can also try the finger pinch hold, which is as simple as holding a sheet of paper between your thumb and each of your fingers for 30 seconds each. “Tell me your hand isn’t gonna feel that work out!” she says.

Nikolajev adds, “One of my favourite exercises—which is also just good for overall back health and taking stress off your hips after sitting all day—is a free hang.” You need an overhanging bar or frame that can support your bodyweight; look for one at a local park. Then, Nikolajev explains, “Just wrap your fingers around [the bar] and hold on. Start at 10 or 20 or 30 seconds. If you are comfortable with that, go for a maximum hold, just to see where you wind up. Then cut that [time] in half and repeat.”

Keep in mind that for your grip to be strong, you’ve got to be able to extend the muscles on the other side of your hand, which will also determine how well you’ll be able to hold onto something. To do this, Nikolajev suggests putting your hands in a bucket of rice and drawing shapes with your fingers. “You’re making outward circles, inward circles, closing your hands, opening your hands, digging them deep into the bucket.” It’s a trick long used by boxers and martial artists to increase their grip and forearm strength, as well as wrist flexibility and power. Plus, it feels cool, and you can do it in front of Netflix.

“In fitness, we tend to focus so much on the big moves: the squats, lunges, flexion, the push and pull,” says Nikolajev. “We very much miss the fact that without strong feet and hands—especially hands—most of those things are impossible to do.” And if hauling all your groceries in a single trip doesn’t feel like something to strive for, buttoning your own darn pants in your golden years very much should be.

Next: 3 Hand Pressure Points to Try Today

My mom was a nurse, and as a kid I swore I’d never be one. Looking back, I think that was more about asserting myself as an individual than any feeling about the work she did. I always had the desire to help people, and I have a mind geared for science. I also really love seeing people get better and supporting them through their challenges. But I was determined to carve my own path.

I started school working toward a degree in microbiology but ended up graduating with a double major in science and nursing. I had shadowed one of the lab courses in the hospital training program and realized I was totally drawn to it. There came a point where nursing felt like the natural thing to do. My mom was doing refresher courses at the same time, so we were learning together and helping each other.

When I graduated, Canadian nursing jobs were hard to find. Thankfully my aunt was a unit clerk on a surgical unit in Calgary, and she helped me get a job right after I graduated. From there, I transferred to a trauma ICU, then to emergency departments. For 25 years now, I’ve worked in critical care.

You have to be on your game in critical care: People’s lives are in your hands. That’s what I loved about it—the intensity, the immediacy, the way you have to work as a team. And I loved advocating for my patients. Not all nurses do that. But I was always the kid who would fight for the underdog, who would stick up for people.

Through my last years of nursing in the hospital I started to see gaps in care for people—maybe because we didn’t have enough resources, definitely because doctors and nurses were overstretched. People were not understanding their diagnosis, treatment or why they were on certain medications. They were not having proper resources at home before being discharged from the hospital. I saw patients and families falling through cracks, but I didn’t realize just how challenging things were until my mom got sick and I went from health care worker to caregiver.

She was diagnosed with colon cancer, had surgery, did chemo—and did great. We thought the cancer was gone. Then it came back in her liver, and we went through the same thing again. Then it came back all through her body. For two years it was an absolute rollercoaster.

During that time my mom moved in with my sister, who is a single mom. They were down in southern Alberta and I was in B.C. It was a challenge for me to help from a distance, especially because I was overseeing the medical side of my mom’s care.

In critical care nursing you have to have boundaries with your patients to protect your own mental health. You see a lot of sad things. With my mom, I didn’t have any boundaries. I thought, I’m healthy, I’m strong, I’m able to do the physical care that she needs. I can talk to the doctors, I can make sure that the test results are being reviewed, I can make sure that she’s on the right medications. I can protect her dignity through this. It absolutely was a way for me to show love to my mom. But I wasn’t prepared for how difficult that was to do from a distance. I was trying to work full-time but I was away a lot, and when I was at work, I wasn’t always present. I ended up taking a leave during the last few months of my mom’s life.

We had a tumultuous relationship. I was the troublemaker of the family. I was a rebellious teenager and that continued into my young adulthood. Thankfully I grew out of it and began to have a good relationship with Mom. The greatest healing happened in the last three months of her life. And I learned a level of love and compassion that I’ve never experienced before. It changed me as a person. Our parents raise us: They change our diapers, they feed us, they cradle us. And I was able to do that for my mom, just hold her like a baby in the last few days of her life.

During that time, I kept thinking, What do people do who don’t have a nurse in the family? How do they get help from someone who can ask the right questions, oversee care and make sure they are getting all the resources they need? What if you don’t have access to a hospice where nurses are trained to talk about death? I was educated in the health care system, I was confident I could get my mom exactly what she needed, and I still struggled. Communicating with the health care team was hard. They were so busy and it was difficult to get the information I wanted about how Mom was doing when she could no longer tell me herself.

After Mom died, I let my permanent position go. I wanted to figure out a way to combine my nursing knowledge and my passion for helping patients navigate our system. I started looking for work and quickly found there were no patient advocacy organizations in Canada. That’s how I came up with Canadian Health Advocates Inc. (CHAI), which is a network of health care professionals available to help people navigate an often confusing system. Our nurses help ensure people get consistency of care, they explain the unfamiliar, they can do research, they can help with paperwork and future care plans—they help patients and families during a scary and emotionally fraught time. It’s the type of service I wish I’d had when my mom was sick.

In a hospital, long-term care facility or hospice, there isn’t a lot of consistency. You see a lot of different doctors. My mom had her primary oncologist but also saw a team of residents, ever-changing nurses, specialists and techs. It’s hard to keep track of who is responsible for what. And you can’t make good decisions if you don’t have all the information or the right education hasn’t been provided. If you’re sick or tired or frustrated, you’re going to retain even less. It’s important to go to your appointments prepared with questions and with somebody to take notes, which is just one of the services CHAI can provide.

We’ve helped close to 300 patients and families now. Often we’re the first people who have actually had time to sit and listen to their stories. A lot of people have lost trust. They’ve lost faith in the health care system, whatever their situation is. There’s so much information out there, how do you begin to siphon through it, how do you decode the medical jargon and get a good understanding of what’s happening to you?

With our large aging population, more and more people are going to be thrust into the position of caregiving out of necessity. And a lot of people will be juggling that with full-time work, children of their own and limited resources. I’m a health care professional and I still would have benefitted from having the support of an advocate. I want to make that available to everyone.

Next: How Are Canadian Caregivers Handling COVID?

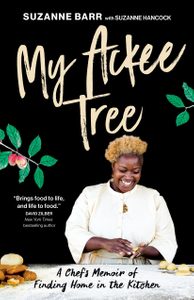

My parents didn’t make a conscious effort to teach me how to cook. They were just cooking all the time, and I was there watching. Staring at my mother’s hands around that bowl.

—

The sky was always blue in Florida. Royal, sapphire, Egyptian, olympic, electric. Tanya and I wanted seasons, to watch leaves fall in autumn and wear snow boots in winter. We sometimes shuffled through family photos of a life before, memories of winters in Toronto with our cousins before we moved to Florida. But the view out my window in Plantation was pretty constant. Blue from the sky and green from a tree that never changed.

The tree, though, was something special: ackee. Jamaica’s national fruit. The poor thing rarely fruited, but it was still like a Jamaican flag in front of our house.

Of all the jobs Mummy asked me to do in the kitchen, cleaning ackee was my favourite.

—

Returning home from a Caribbean market, Daddy places a whole sack of ackee on the table. Bright-red fruit peeks from the bag. Each pod is the size of Mummy’s palm, and they look like beautiful undersea flowers, opening.

Tanya and I stand beside her at the counter. “Don’t mash up de ackee.”

We roll our eyes. “We know, we know. You tell us every time.”

She sucks air through her teeth from behind pursed lips, then lets out a short, sharp kiss. It’s a technique my mum mastered before my time. Jamaicans are experts at kissing teeth.

A short kiss means minor irritation. A longer, deeper kiss means that Mummy is vexed. Kissing teeth can indicate annoyance, anger, and even joy…

It’s only a short kiss this time, and Mummy is showing us that she disapproves of our eye-rolling and our sass.

“Put the seeds here in this bowl.”

Her accent was subtle, but Jamaican Patois would shine when she was vexed, or when she was reminiscing with one of her friends.

“Cha” (no, man) was one of her staples.

“Cha, cant bada with de childe, pickney de too facety.”

Mummy had an arsenal of dialects and accents for everyday use.

I didn’t love the actual work of cleaning ackee—gently separating the fleshy parts of the fruit from the shiny black seeds—but I loved knowing that we’d have ackee and saltfish the next morning. Ackee has a mild flavour, kind of nutty, and a buttery texture that pairs perfectly with salted fish.

“This one isn’t open, Mummy.”

She grabs it out of my hand.

“It’s poisonous. The fumes will kill you,” she says.

It always shocked me, that fact. If it’s eaten too soon, before it opens on its own, it can be toxic.

She sifts through the bag, pulling out any closed pods, and places them on the marble windowsill above the sink. It’s where she puts tea bags she’s only used once, the kitchen sponge, her beloved spider plant.

Ackee flesh gets under my nails. It’s kind of slimy but not gooey. Firm yet soft to touch.

“It looks like a brain!” Tanya and I giggle. “

Cheeky innit! Stop playing with the food and finish up,” Mummy says firmly.

A seven-pound bag of ackee turns into one pound of flesh. Shells go in the garbage, black seeds are sprinkled in the backyard in hopes of another tree.

Cooking salt cod is a process. Mummy soaks the fish overnight in water, and then drains it the next day. She adds fresh water and brings it to a boil. The water spills over, and she kisses her teeth; she drains the water, boils it again, drains again, boils it for a third time, and drains it once more. Each time she changes the water, more salt is pulled from the fish.

When the fish is ready, she parboils the ackee flesh. Then she flakes the fish into big, succulent chunks and adds crispy sliced bacon, tomatoes, thyme, and scallions. Cooked ackee looks like scrambled eggs with its firm fluffiness and light-yellow hue.

There’s power and deep memories in that combination of flavours for me, and that’s why I rarely cook ackee and saltfish myself. It sits too heavy on my heart. All I think about with that dish is my mum.

Excerpted from My Ackee Tree by Suzanne Barr and Suzanne Hancock. Copyright © 2022 Suzanne Barr and Suzanne Hancock. Published by Penguin Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: This Rosemary Socca Is Best Served With a Glass of Rosé on a Summer Afternoon