Sue

Float nurse who fills staffing gaps in medical and surgical units

“I noticed people weren’t eating their lunches or dinners, so I started bringing more protein-focused snacks, like bars or shakes, to help them easily refuel.”

Sue loves being kept on her toes. She usually works night shifts, when there are fewer nurses, doctors or allied health care staff available. And though she regularly works with different teams, she finds ways to build connections and community. “Time just gets lost when we’re scrambling on nights,” she says, so she keeps snacks on hand to share with colleagues when they need an energy boost, and Tim Hortons or Starbucks gift cards to buy co-workers coffee in the morning. “After a long shift, when you’re tired and often feeling underappreciated, having a little treat to look forward to can be a pick-me-up.”

“I drink a lot of caffeine, so I always have instant coffee sleeves and bags of tea within reach, and to hand out. I also like to pack around little apple cider mixes or pumpkin spice mixes just to liven things up! And to have an option for people who can’t have caffeine.”

During a recent shift, Sue was on a unit with one charge nurse and two graduate nurses with less than three months of experience. She says everyone, including the inexperienced nurses, is expected to take on eight patients: “The strain and burden can get overwhelming … we are called heroes all the time. But we’re also human. We’re not martyrs and we need a break as well.” Sue says it’s easy for nurses to get tangled up in completing tasks without looking after their own health and well-being, so she feels compelled to help her colleagues where she can, usually by providing food and drink.

(Related: 10 Medicine Cabinet Essentials Nurses Always Keep on Hand)

Laura

Critical care nurse and ER nurse

“I carry my trauma shears everywhere. They’re handy to have if you need to be able to get something off quickly. One of my paramedic colleagues uses them on the road—they can cut through a seatbelt; they can spider a windshield. I once used them to cut flame retardant clothing off a firefighter who came into the trauma unit.”

Laura is someone people know to go to for self-care in the middle of a shift. “We treat ourselves so that we can continue to do our job and continue to provide care. I think that we nurses have been doing that for a long time. But the feeling of that happening now is more at the forefront than I’ve ever felt before.” She likes working in a dynamic, fast-paced work environment: “That’s what I feel passionate about, and that’s what drives me … but it’s also hard when you don’t feel like you’re making a dent or an impact because you’re just stretched so thin.”

“I like having nice-smelling things on hand to make my patients feel comfortable. It feels good when you can offer something as simple as that, but it has such an impact for people.”

Laura says that because nursing is an essential profession, nurses don’t have the bargaining power that other professions may have. Part of the problem, she says, is also “because we are a female-dominated profession” and taken for granted. She says Ontario’s Bill 124, which limits annual salary increases to one percent for most public-sector employees, feels like a slap in the face. “We’ve been the backbone of trying to get the entire province through this pandemic, looking after people at our own peril sometimes.”

(Related: What a Nurse Keeps in Her First-Aid Kit at Home)

Roxie

Family health nurse

“Because of the ongoing drug crisis and the war on people who use drugs, there are people dying every day of an overdose. Having a Naloxone kit [which includes a fast-acting drug used to temporarily reverse the effects of opioid overdoses] is really, really important.”

Roxie works in a clinic Monday to Friday, and spends her free time doing volunteer outreach work for people who face structural barriers to care. She attends events like encampment evictions and rallies to support Black and Indigenous lives so she can offer on-the-ground treatment.

“Snacks and water keep me going because I’m on my feet for hours at a time. My colleagues and I, even in clinic, we forget to drink water and so we’re constantly reminding each other to do that.”

Roxie is part of the Street Nurses Network, a group working with people experiencing homelessness. “As a nurse you’re used to working in a clean clinic or hospital space, but when you’re outside meeting people exactly where they are, that’s different. You’re just using the space that you have. One time I saw a client at a grocery store bathroom, and that’s where I gave an injection. I’ve given an injection on the steps of a church. Managing your environment is definitely something that’s different here than other forms of nursing.”

Sahil Gupta is an emergency room doctor based in Toronto. This story originally appeared on healthydebate.ca.

Next: Caring For My Dying Mom Showed Me That Caregivers Need More Support, Too

A few years ago, Dr. Nicole Woods’ father needed a medical test. The physician was clear: no carbs beforehand. He rattled off a lengthy list of foods to avoid. Woods’ mother struggled to figure out what to make for dinner before landing on options like cassava and dasheen. “These are West Indian foods that are 100 percent carbs,” Woods says. “But they weren’t on the list.” Instead, it was heavy on squash, turnip and beets.

The doctor failed to take into consideration key factors, like her father’s background, his age and the likelihood he’d tuck into a plate of beets. “The physician didn’t think to himself, Who is this person and what does he normally eat?” she says. “They don’t do that unless they’re prompted to by their training.”

Plenty of us check out our doctors’ credentials online or take a surreptitious glance at the diploma on the wall, searching for some sort of confirmation of what they know. But we’re a little less focused on how exactly those doctors learn, which is where Woods’ work comes in. As an education scientist at Toronto’s University Health Network, she wants to expand the model of training for medical professionals, which tends to make a lot of assumptions about the default patient (middle-aged white guy) and even the default physician (same). However, when medical students are exposed to basic sciences like psychology and sociology, she’s found they’re far likelier to understand the human condition—and adjust their approach accordingly. Here, she explains why doctors need to think like chefs and why patients should channel their inner toddler.

(Related: “The Uncertainty Was a Big Piece. And I Couldn’t Get Answers”)

When it comes to med school, what sorts of science has the curriculum generally focused on?

Historically, the way we’ve trained students is to take reasonable guesses about what types of knowledge a physician is going to need, and then work our way backwards, designing programs that provide that knowledge. So it’s largely biochemistry, anatomy, maybe a little bit of physics. But it’s been a very limited definition of what science counts in medicine.

What are the implications of that?

It limits what we can do for our patients. Limited sources of knowledge mean limited opportunities for us to really understand what’s happening with our patients. That’s why we want to bring in concepts from psychology, from sociology, from kinesiology, from linguistics. They help people think through clinical problems. My work really focuses on making sure that students don’t just know what to do. They also know why they’re doing it.

How does linguistics, for example, help with clinical reasoning?

I can easily give a physician a checklist for breaking bad news. The challenge is that not every patient is the same and not every moment is the same—so a checklist isn’t going to cut it. A bit of linguistics will help you understand not just the steps you take but the words you say, and why certain words are more helpful. If I understand the why, and I have a patient in front of me for whom the checklist doesn’t apply, then I can modify it and make it work for them.

I’ve had experiences with my own family physician where it was clear to me that they didn’t appreciate my understanding of science. So as they were describing to me potential complications in my pregnancy, they were doing so at a level that didn’t reflect what I could bring to the conversation. Again, they were probably going through their checklist. But what they hadn’t done was think carefully about their choice of words.

(Related: “For All Those Years, No One Told Me Anything”)

So understanding the why allows you to improvise better in a medical setting?

Exactly. It allows you to make a responsible choice about when you need to adjust and innovate. Because you can’t do that safely if you don’t really understand why you were doing something in the first place, right? A colleague of mine uses a cooking example: if you’re missing a bay leaf, but you don’t know what it’s meant to add to a recipe, you won’t know how to replace it.

What do bay leaves even do?

I couldn’t tell you! So I’m stuck. But someone who knows what it’s supposed to do in the first place might be able to make a reasonable substitution. It’s very, very similar.

How has the pandemic changed your work’s focus?

Pre-pandemic, we were thinking a lot about changes in the science itself, helping physicians keep up with this onslaught of new technologies. But then the pandemic hit and some of the science stalled. People working in health care right now are absolutely exhausted. And what used to be routine care has become so complicated. Take just a basic family doctor visit—now you have to figure out how to do a virtual physical examination. That takes a basic skill that physicians would have been learning from day one in medical school and makes it incredibly complicated. So forget the newfangled robot thing: we’re going to have to think much more about communication, collaboration and some of these touchpoints of virtual care.

There’s also been an explosion of interest over the pandemic in adaptive expertise. And what that concept essentially says is that you’re not an expert because of the knowledge in your head, but because you can use it to create new knowledge in the face of novelty and ambiguity. It’s recognizing when your knowledge applies, and when you have to be creative in the moment.

It does feel that expertise has been somewhat denigrated during the pandemic.

Yeah, it’s difficult. I try very hard through all my work to focus on what people bring to the table and not who they are. We certainly want to value lived experience. But lived experience is not expertise.

We’ve been inundated with information over the past two years, and some of it is really sticky—like washing our hands to ward off Covid, even though we now know the virus is airborne. Why can’t we shake that early information?

Education science is all about using those first academic disciplines, and you’ve just brought in some basic cognitive psychology. The first thing in any list is very memorable. The last thing in any list? Very, very memorable. So the fear that we were experiencing at the start of the pandemic, when we were told to wash our hands—that emotion makes the information very difficult to forget. The problem is, it might not be accurate.

How can patients become better learners?

Patients ask a lot of what questions: What is this? What’s going to happen tomorrow? What do I do next? I think that patients can be better learners by asking more why questions: Why does this happen? Why do I need to do that? We call it the toddler rule, because toddlers are going to ask why, why, why? until you’re like, please stop. In our lab, everyone gets two why questions. Then you have to go read a book.

Next: What Happens When Doctors Don’t Listen to Patients

While spots like the ribs and the throat are generally very painful, in reality, every person you meet with a tattoo will likely give you a different answer as to what hurts most. After all, pain level and pain tolerance are subjective, and what’s killer for one person might be a blip on the radar for another. That said, there is some consensus about what areas hurt more than others.

Most painful to tattoo

Sean Dowdell, who founded Club Tattoo alongside the late Linkin Park vocalist Chester Bennington, says the most painful body part he’s ever had done was his wrist. “I’m fully sleeved,” Dowdell says. “I have full back pieces…but for me it was the inside portion of my wrist, right where the flex point is.” Since he has owned and operated Club Tattoo, from 1995 to the present, he says he has come across people who feel the same way.

As for some of the other most painful experiences he’s witnessed: “From seeing my other employees and tattoo artists and clients, I think the stomach is a very painful place to get tattooed. And the back of the knee.” The neck, the throat, and the ribs also top the list.

Least painful to tattoo

The least painful places to get a tattoo are areas of your body with fewer nerve endings. Think outer shoulder, calf, buttocks, and outer arm.

While people generally focus on the location on the body, Stanley Kovak, a cosmetic physician, theorizes that pain is more about size. The more you work and the longer you work on the body, the more it hurts. When a tattoo is especially intricate, it also requires more shading, more colouring, and various types of needles—all of which increase tattoo pain.

Other factors that affect pain

Certain health issues may make you more sensitive to pain. “Some people have previous injuries and they have heightened sensitivity in certain parts of the body,” Dowdell says. Some tattoo collectors say that tattoos hurt more on the bone, others will say it’s a matter of how thick or thin the patch of skin is, but Dowdell doesn’t think either of those factors mattter. “It’s definitely a nerve ending issue,” Dowdell explains. “As far as [skin] thinness goes, you can get the top of your hand tattooed, and that’s pretty thin, and that’s not very painful. But if you get your finger tattooed, it’s got a little bit more skin [and] a little bit more tissue, but is a lot more painful.”

Age also has a lot to do with the amount of pain experienced while getting tattooed, says Kovak. Younger skin isn’t as painful as older skin to tattoo because it’s tighter and can better absorb the ink.

Some artists are more heavy-handed than others, making for a more painful experience. If you’re sensitive to pain, ask the studio for a recommendation on a “gentle” tattoo artist.

What about…down there?

One would think that getting tattooed in the nether regions of the body would incur infection the most, but actually, both Kiva and Dowdell say otherwise. “Anytime you have mucosa (mucus membranes)—and this is going to be more on females than males—and you’re breaking that tissue, you can expose it fairly quickly to bacterial infections,” Dowdell shares. “But the good news is they’re generally not exposed, so you’re a little less prone to infections or problems because you keep it covered.” Kovak agrees, adding, “Unless someone has a predisposition to have MRSA [or] is a diabetic, the risks are not any more than any other kind of skin infection to treat.”

Most likely to get infected

Infections arise because of bad bacteria, so when thinking about which tattoos are most likely to get infected, think about which parts of your body have the most interaction with bacteria—often times, that’s the feet. “A lot of people don’t realize how exposed their feet are to bacteria,” Dowdell says. One of the biggest risks for infection may be right in your own home. “People don’t realize how quickly being exposed to pet dander on a fresh tattoo can really cause an infection that can lead to big problems.” And simply walking down the street can be an issue, especially if you’re wearing flip-flops or other open-toe shoes. So if you do get a foot piece, be sure to clean it well while it’s healing. The same also goes for hands, since your hands and fingers come into contact with tons of bacteria every day.

Most dangerous tattoo

Tattoos have become much more widely accepted in today’s day and age, but there are still certain types that only the most daring go for. One of those spots, which is also the most dangerous a person can get, is the eyeball. For most people, getting their eyeballs tattooed wouldn’t ever cross their minds. However, those who do decide to get inked there run a potentially huge risk. “With an eyeball tattoo, there’s a higher risk of getting an infection. Plus, if you get an infection in the eye, it has serious potential problems including vision loss,” Kovak says.

The aftercare directions you need to follow

Skin infections are always a possibility with tattoos, however, they are generally easily treated with antibiotics, says Kovak. Skin infections also are less likely to occur if you get tattooed at a clean and responsible shop that’s licensed (licensing requirements vary depending on location)—and if you follow your aftercare instructions. “A lot of people don’t follow the directions on not jumping into public pools, lakes, [and] rivers for at least two to three weeks after they get a tattoo,” says Dowdell. The Club Tattoo owner also notes that people often have misconceptions about the extent of aftercare. “They think because [a tattoo] is small, it’s going to be very easy to take care of, and that’s not always the case.”

Tattooers also tend to advise against intense physical activity or going to the gym with fresh ink, as gyms can be breeding grounds for bacteria. “I don’t tell people not to work out, I just tell them to keep it covered when they work out, says Dowdell. “Really simple bacterial infections like MRSA can pop up in a gym very easily, just by someone not wiping down a machine. If you’ve got an exposed tattoo and you set it on the machine, you can contract a very serious bacterial infection really quick.”

Tattoos hurt to remove, too

As a professional who regularly performs laser tattoo removal, Kovak is able to observe the other end of tattoo pain. With removal, it’s not so much about the location of the tattoo, but the size. If it’s larger, he usually uses a topical anesthetic.

Next: 5 Stylish Fanny Packs that Can Help Lessen Back Pain and Improve Posture

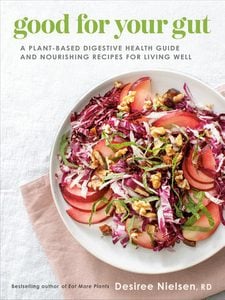

This salad is full of flavourful Mediterranean ingredients like bitter radicchio, tart plums, crunchy walnuts, and creamy yogurt.

We really do not eat enough bitter vegetables because our palettes tend to be overly used to salty and sweet foods. Bitter greens such as radicchio and rapini stimulate digestion and are a wonderful balm for someone who craves sweets. Mint adds another layer of flavour to this special salad and helps to soothe the gut.

DAIRY-FREE • GLUTEN-FREE • GRAIN-FREE • HIGH-FODMAP • VEGAN

Plum and Radicchio Salad with Tahini Yogurt Dressing

Serves 4

Ingredients

Tahini Yogurt Dressing

- ½ cup (125 mL) coconut yogurt

- 2 tablespoons (30 mL) tahini

- 1 tablespoon (15 mL) freshly squeezed lemon juice

- 1 small clove garlic, grated with a microplane

- ½ teaspoon (2 mL) salt

- ½ teaspoon (2 mL) organic cane sugar

- ½ teaspoon (2 mL) ground sumac

- ¼ teaspoon (1 mL) red chili flakes

Plum and Radicchio Salad

- 1 small head red radicchio, finely shredded

- 4 firm black or red plums, pitted and sliced

- ¼ cup (60 mL) raw walnuts, chopped

- ¼ cup (60 mL) Medjool dates, pitted and chopped

- ¼ cup (60 mL) fresh mint leaves, thinly sliced into ribbons

Directions

- Make the tahini yogurt dressing: In a small bowl, whisk together the coconut yogurt, tahini, lemon juice, garlic, salt, cane sugar, sumac, and chili flakes. If needed, add 1 to 2 tablespoons (15 to 30 mL) water for desired consistency. Store in an airtight container in the fridge for up to 4 days. (It makes a great veggie dip.)

- Make the plum and radicchio salad: In a medium bowl, toss the radicchio with half of the dressing. Layer the plums, walnuts, dates, and mint over top of the radicchio. Serve with the remaining dressing on the side.

Excerpted from Good for Your Gut by Desiree Nielsen. Copyright © 2022 by Desiree Nielsen. Published by Penguin Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: This Peach, Burrata and Basil Salad Makes a Sweet and Savoury Summer Appetizer

With increased awareness on issues like climate change and social injustice, many investors are now concerned about where their money goes. One option being explored is something called impact investing, which means aligning your moral compass with your investments.

“More and more people realize the futility of investing in businesses that create or exacerbate social and environmental problems [globally],” says Bonnie Foley-Wong, author of Integrated Investing and founder of Pique Ventures, an investment firm that specializes in impact investing. “They are motivated by purpose in other aspects of their lives—like their work and purchasing decisions—and have realized that they can make purpose-driven investments, too.”

Impact investors choose organizations that have a good impact on the world. And in recent years, millennials and women have been at the forefront of the shift to ethical investing.

Here’s how to determine if it’s a strategy that’s right for you.

ESG versus SRI: What’s the difference?

Socially responsible investing (SRI) and environmental social governance (ESG) investing are two different approaches to impact investing.

The three basic measurable principles of ESG investing are the impact on the environment, social impact and governance (a company’s overall leadership). “Look for companies that are at the very least doing no harm and at the very best improving the planet through their products and services,” says Marissa Bronfman, the former chief brand officer at Kizmet Impact Capital, an impact investment fund.

SRI investing goes further by actively excluding or selecting investments based on certain ethical principles. It’s a strategy that’s unique to each investor. For example, gender-lens investing integrates gender analysis into decision-making. Before becoming associated with a company, investors assess that company’s commitment to having more women in executive roles, and how well they score on pay equity and other workplace practices that benefit women, like generous paid leave.

How can I measure the impact?

Beyond the risk of not earning the desired return or losing money, which is part of any investment, impact investors consider risk over a longer period of time, and the impact of a decision on future generations. Impact investors also think about who is taking on disproportionate risk—for example, whether the risk has been passed to employees, suppliers, customers or communities. This might exclude a company that engages in questionable business practices or profits from a trade in weapons.

How do I identify legit impact investing from marketing hype?

It’s hard to invest ethically when you’re unsure where to find trustworthy information. There is the risk of investing in a company that is greenwashing, for instance. “A company can use environmental language or environmental colours to position their product or service as something good for people and the planet,” explains Bronfman.

To familiarize yourselves with impact investing, start following accounts on social media such as @mymeaningfulmoney, @janinerogan, @bonnieowong or @financeforchange. You could investigate companies whose products you already use to see if they offer investment opportunities. Bronfman encourages everyone to do their due diligence on industries and companies.

There are also publicly available impact-oriented resources, like the sustainable development goals from the United Nations. Third-party rating agencies also offer ESG ratings, but they can vary dramatically, so use them with other metrics.

Developing an impact investment strategy sounds complicated, but Foley-Wong believes that a lot of it comes down to your priorities. To start, you can “dedicate a small portion of your disposable income to investing and then make sure it aligns with your values,” says Bronfman.

Remember that impact investing is about doing the right thing in the long term, not for a quick buck. But the returns will be even sweeter when you know they’re aligned with constructive, positive change.

Next: I Had $1.11 in Savings. Here’s How I Improved My Relationship With Money

Five years ago, on March 8, I was washing dishes, and I felt a fatigue I have never felt before. It was a chore to stand there. I wanted to go to bed. But I was having people over for coffee. They came and went, and I had severe pounding in my chest but figured I should start dinner. I couldn’t tell you what was wrong. It wasn’t a pain. It felt like I just didn’t have enough room in my chest for the things I have in my chest, like my heart and my lungs. I took my blood pressure and my pulse—we have the equipment because we need to check my husband’s frequently—and both were very low. I called my family doctor and told her some of the things I was feeling. I said, “Can I come in and see you?” She told me to go to emerg. I thought, Well, that’s rather dramatic, but she insisted.

Looking back, I was quite worried about how it would worry my husband. He’s had significant health issues throughout the years, and I didn’t want to stress him. I’ve known him for 40 years, and we’ve been together for 25. We don’t have kids. That’s another layer of intensity because it’s just the two of us. I understood later that worrying about causing worry to others is a barrier women put in front of ourselves.

But off we went to the hospital I used to work at. Part of my work revolved around health equity. That included gender, but I never personalized it.

The doctor told me I had had a heart attack. I was in denial. I didn’t have the typical blockages or high blood pressure. My ECG was normal. But my cardiac enzymes were very high. I was going on my father’s experience—he’d had cardiac disease, and I’d looked after him, and his ECG was never fine. So I said to the doctor that I’d look into it and asked if I could go home. He said no. My husband was pulling out his hair—he was baffled that I thought I could go home.

(Related: 15 Heart Attack Prevention Tips Every Woman Must Know)

In the end, they never did find out the reason for my heart attack. When I was being discharged from the hospital, the cardiologist said I was obviously under terrible stress, and that’s why I had it. That shocked me. I was upset and insulted. I wasn’t stressed. But it was very hard for me that they didn’t know why I had had a heart attack. How could I prevent this from happening again if no one knew what caused it? The uncertainty was a big piece. And I couldn’t get answers.

A close friend who had had heart issues a few years before told me to get a referral to Women’s College Hospital’s cardiac rehab program. When I asked my cardiologist, he said it hadn’t occurred to him that I would be interested in the program. Of course I’d be interested! It was life-changing. There was physical rehab and education. They were able to teach me how and when to use my nitroglycerine spray when I have angina. No one told me before that I should be using nitro spray if I continued to have chest pain. It was meaningful for me to be there with a group of women supporting women and talking to one another.

One of the biggest barriers for me to get care was I didn’t know I was in trouble. I didn’t know what the signs were. I didn’t worry about heart disease, even though my father had cardiac disease for many years and my mom died of a dissected aorta. That wasn’t my life. But I understand now that if I don’t take care of myself, then I’m not going to be able to take care of others.

This essay is part of a larger package looking at women’s health gaps in Canada from our June/July 2021 print issue. Read more:

Women’s Health Collective Canada Is Addressing the Gap in Women’s Health

“For All Those Years, No One Told Me Anything”

“One Ob-Gyn Diagnosed Me with PCOS. Another Ob-Gyn Said I Didn’t Have It”

Get more great stories delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for the Best Health Must-Reads newsletter. Subscribe here.

When Lisa Mattam found her nearly three-year-old daughter slathered in face cream, her first reaction was to tell her, “You can’t have that on your skin.” In that moment, Mattam realized: If the product wasn’t safe enough for her daughter to play with, it wasn’t good enough for her own skin, either.

Mattam thought about the products that she did let her daughter play with and realized they were always the ones her parents brought to Canada from Kerala, India, where Mattam’s family is from. “Those were the ingredients and formulas that I trusted,” she recalls.

Kerala is the epicentre of Ayurveda, a natural system of medicine based on the idea that ailments are linked to an internal imbalance caused by stress, the environment and diet. Ayurveda, which means “the science of life” in Sanskrit, uses plant-based remedies, yoga and meditation to restore balance and health, and it has been studied for centuries. “Growing up, oiling my hair or using turmeric on a pimple, that was just how I was raised,” says Mattam. “But I didn’t realize how steeped in science it all was.”

Mattam reached out to two Ayurvedic doctors in Kerala and began to formulate the products she wanted by reverse engineering them. “I would tell [the doctors] what I wanted the product to do, and they would tell [my team and me] what ingredients and proportions we needed,” she explains. “I really wanted to bring [natural beauty products] to people and the way I knew how was to get this old-world science, work with doctors in India, and then prove it with modern science.” In 2015 she launched Sahajan, an Ayurvedic skin and hair care line built on all-natural ingredients that are scientifically proven to work.

One of the line’s star ingredients is turmeric, which “has really risen to popularity in the last couple of years because it’s a known anti-inflammatory,” says Mattam. Sahajan’s turmeric-loaded Brightening Mask is inspired by the haldi ceremony that’s performed in many parts of India before a bride gets married. “The bride is covered with a mix of turmeric and ingredients like rosewater and fruit,” Mattam says. “It’s meant to give you your best glowy skin, and our mask was inspired by that. It’s really an Ayurvedic recipe for hyperpigmentation.”

Sahajan’s Nurture hair oil, another bestselling product, is inspired by the Ayurvedic hair oil treatment, where oil is applied directly to the scalp and hair from root to end, combed through, left for several hours and then washed out with shampoo. The result is shiny, soft, strong locks. “It’s been shown to strengthen the resilience of hair and help with hair loss, shine and lustre,” says Mattam.

Hair oiling treatments are a practice with deep roots in India and other parts of south Asia, and it’s often a family affair. “Most South Asian girls have a memory of—whether it’s their mom or aunt, or in my case, my dad—having this very intimate familial moment,” says Mattam. This intimacy is depicted on-screen in the latest season of Netflix’s hit show Bridgerton, as the Sharma sisters apply hair oil to each other’s locks. “Does [hair oiling] work? Absolutely,” says Mattam. “But there’s also something incredible for familial relationships when someone does that with your hair. There’s nothing like it.”

While popular media like Bridgerton make ancient rituals like hair oiling buzzy, these practices and ingredients have a rich history that isn’t always recognized. “It’s important to have authentic voices bringing these products and ingredients forward,” says Mattam. “Not just for the sake of representation, but for the sake of understanding so that those stories are authentically shared.”

This story is part of Best Health’s Preservation series, which spotlights wellness businesses and practices rooted in culture, community and history. Read more from this series here:

This Company Is Bringing Ethiopian-Grown Teff to Canada

This Soap Brand Is Sharing the Healing Power of Inuit Tradition

This Canadian Soap Brand is Rooted in Korean Bathhouse Culture

Meet Sisters Sage, an Indigenous Wellness Brand Reclaiming Smudging

Get more great stories delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for the Best Health Must-Reads newsletter. Subscribe here.

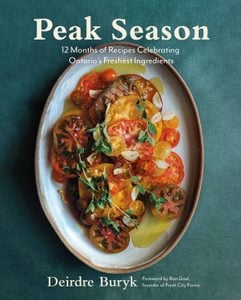

Native to Ontario in their wild form, blueberries are teeny little gems with plenty of amusement for the palate. When markets are packed with blueberry stalls from July through to August, you have plenty of opportunity to try a delicately sweet true-to-Ontario fruit. If you look closely, you will notice a silver coating on a blueberry—that is there to protect them, so wash only when you are ready to eat them.

Though they are quite spirited on their own, a little rosemary can heighten the flavours of the blueberry with its lemon-pine pungency, making for two nice partners, especially when served on a puffy Dutch baby pancake.

Dutch Baby with Stewed Rosemary Blueberries

Serves 4

Ingredients

Stewed Rosemary Blueberries

- 1 cup blueberries

- 1 tablespoon water

- 1 tablespoon granulated sugar 1 sprig rosemary (or 1 teaspoon dried)

Dutch Baby

- ½ cup (65 grams) all-purpose flour

- ½ cup (125 mL) oat milk (or any milk)

- 3 eggs

- 2 tablespoons granulated sugar

- ½ teaspoon kosher salt

- 2 tablespoons (30 grams) unsalted butter, room temperature

Directions

In a medium skillet over medium-high, heat the blueberries and water. Once the liquid begins to form little bubbles, reduce the heat to medium-low and add the sugar and rosemary. Stir and stew until the sugar has dissolved, 2 minutes. Remove from the heat and set the stewed rosemary blueberries aside, removing any woody stems of rosemary.

In a blender or food processor fitted with the blade attachment, place the flour, milk, eggs, sugar, and salt. Blend for 10 seconds, scrape down the sides, and then blend for another 10 seconds. The batter will be quite loose (like a liquid). Allow the batter to rest in the blender for 20 to 25 minutes. This will give the flour a chance to absorb the liquid and the batter to thicken.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 425ºF (220ºC). Place a 12-inch (30 cm) oven-safe skillet in the oven to warm along with the oven. When the batter has finished resting, remove the skillet from the oven (remember, it will be hot, so use oven mitts). Add the butter and swirl the pan to melt the butter and coat the bottom and sides

of the pan. Pour the batter into the butter-coated skillet and tilt the pan to spread the batter evenly across all sides of the skillet.

Bake until the Dutch baby has puffed into a golden cloud with darker brown, crispy edges, 15 to 20 minutes. Serve hot from the pan and top with your stewed rosemary blueberries.

Excerpted from Peak Season by Deirdre Buryk. Copyright © 2022 Deirdre Buryk. Photography © 2021 Janette Downie. Published by Appetite by Random House, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: This Peach, Burrata and Basil Salad Makes a Sweet and Savoury Summer Appetizer

If you think you’ve been drinking more since the Covid-19 pandemic hit, a study shows you’re not alone.

The report, commissioned by the Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) shows that one in five Canadians who are staying home more have reported an increase in alcohol consumption since the pandemic unfolded. (Stress and boredom are the most common causes, though a lack of regular routine and loneliness aren’t far behind).

Currently, Canada’s low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines recommend women have no more than two drinks a day to help reduce long-term health risks. Research from the Journal of Studies of Alcohol and Drugs, however, pushes that number down even further, suggesting that Canadians should have no more than one drink a day.

One drink, by the way, is measured as:

- One 341 mL (12 oz.) bottle/can of 5 percent beer, cider or cooler

- One 142 mL (5 oz.) glass of 12 percent wine

- One 43 mL (1.5 oz.) serving of 40 percent distilled alcohol (rye, gin, rum, etc.)

But don’t despair: Cutting back on your alcohol consumption is a lot easier when you have a tasty alternative. Here are a few of our favourite healthy mocktail recipes.

If you love frozen cocktails

Ingredients:

- 1 cup seedless watermelon

- 3 mint sprigs

- Splash of lime juice

- 2 or 3 ice cubes

Instructions: In a blender combine seedless watermelon, ice cubes, mint sprigs, and lime juice. Blend until smooth.

If you love fruity vodka sodas

Ingredients:

- 1 cup soda water

- 1/2 cup freshly squeezed grapefruit juice

- Handful of ice

- Stevia

Instructions: Combine soda water, freshly squeezed grapefruit juice and a handful of ice. For extra sweetness, add stevia.

If you love Long Island Ice Tea

Ingredients:

- 1 to 2 tbsp DavidsTea Country Lemonade

- 2 or 3 ice cubes

Instructions: Add tea leaves to 295 mL hot water, steep for five minutes and top with ice.

Next: 6 Non-Alcoholic Beers You Need on Your Radar

In 1988, abortion became legal in Canada, and today, new initiatives continue to be introduced to improve access to safe abortions for all citizens. Most recently, the Government of Canada committed to giving millions in funding for projects by Action Canada and National Abortion Federation Canada to offer financial assistance for people who need to travel for the procedure. But that’s still just one of many secondary costs that can be a barrier to abortion.

In most cases, the procedure itself—whether that be a surgical abortion or the abortion pill—in Canada is free for those with a Canadian health card. But then there’s the cost of taking time off work, child care, and travel and accommodation costs, if you live outside of a city centre where abortions aren’t available. That means for some people, an abortion in Canada can cost thousands of dollars.

We sat down with Action Canada’s director of health promotion Frédérique Chabot to learn more about the hidden costs around abortions in Canada.

First, can you share a bit about the two abortion options in Canada: a surgical abortion and the abortion pill?

The term “surgical abortion” is kind of a misnomer—it’s not actually surgery. Some people call it a procedural abortion, but people just know it as surgical abortion. Most of those abortions happen in the early stages of pregnancy, so before 12 weeks, which is when the majority (about 95 percent) of abortions are done. The way it works is you go for an appointment at a clinic or hospital. An instrument is inserted through the cervix and it aspirates the contents of the uterus. The procedure takes about 5-10 minutes. After the procedure, the patient goes to the recovery room for up to an hour, is usually given some pain management medication, and there’s some bleeding. Different procedures are used to terminate pregnancies at later gestational stages but it’s all with instruments through the cervix.

The abortion pill is usually called “medical abortion,” but a better name is “medication abortion.” People in Canada can access a medical abortion up until nine weeks; after that, a surgical abortion is the only option for ending pregnancy. A medical abortion is when an abortion happens through two medications. After talking to a doctor and getting a prescription, you take the first called Mifepristone, which is a progesterone blocker. Progesterone is the hormone that helps the pregnancy stick and continue to evolve—so if you block it, the pregnancy stops evolving. After 24 hours, you take Misoprostol, which is a medication that makes the uterus contract. The tissues are expelled; it’s basically a miscarriage. There will be cramping and bleeding. It takes two to three days to complete, and it can happen at home. There’s a follow-up appointment with a doctor by phone or in person to make sure that everything went well.

How much does a surgical abortion and a medical abortion cost in Canada?

Both surgical and medical abortions are insured medical procedures. This means all you have to do to get the procedure for free is show your health card at the clinic, hospital or pharmacy.

But, if you’re outside of your home province or territory, you can get coverage only for a surgical abortion—not the abortion pill. For example, if you’re from Ontario and visiting or living in Alberta, you’re entitled to getting an appointment with a doctor and your province will be billed for your surgical abortion—but there’s no such arrangement for medication. So if you need the medical abortion pill in another province you do not live in, you have to pay out of pocket, and the price can range from $350 to 450.

There’s also another potential cost, particularly if you are a resident of Ontario. New clinics in places like Brampton and Mississauga are charging people administrative fees. So, even though the medical procedure and the doctor fees are covered by the province, Ontarians are asked to pay out of pocket for the administrative fees, which can range from $50 to 400. This is in violation of the Canada Health Act. It’s a problem that can only be addressed by the provincial and the federal governments.

Is there anywhere else in Canada where people seeking an abortion are treated unfairly?

In New Brunswick, there’s an anti-choice regulation, which is also in violation of the Canada Health Act, because it restricts abortion care to hospitals—it can’t happen in a clinic. The government has funded three hospitals to offer abortion. Two of them are in Moncton, one of them is in Bathurst, and they have a very early gestational limit [14 weeks]. So when people need services beyond that time, or don’t have money to travel, people are asked to pay for a surgical abortion or medical abortion, ranging in price from $500 to 1000.

There’s also a possibility of a fee in Nunavut, because there’s no agreed universal cost coverage for the medical abortion pill. The appointment would be free, but there’s about 15 percent of the population that is not covered by a federal program to cover the cost of the pill.

How accessible is abortion in Nunavut and other remote places?

Outside of major cities, especially in the territories, there are fewer points of services, so people have to travel for health care. This means people seeking an abortion have to pay for travel and accommodation and everything else that comes with having to access an abortion that’s not in your community. It’s a very common medical procedure—one in three people that can be pregnant will have an abortion in their lifetime—but it’s not treated as such.

How much are the travel costs?

It’s a significant expense—plus, people have to take time off work, find childcare or eldercare, pay for transportation and accommodations. And it might require a few days. If the pregnancy is in its first few weeks, a procedure will be a day-long, but if it’s later in the pregnancy, the procedure can take three to five days.

Action Canada as well as the National Abortion Federation Canada have received funding that can cover travel, accommodations, and incidentals (taxis, food, etc.). A good portion of the funds goes to staffing costs for people who answer the phone lines and act as patient navigators. Another portion is reserved for financial aid that is available to anyone in Canada who is facing barriers to abortion. This past year, we have supported over 130 people with our donor-funded emergency fund. People who are not covered by the Health Canada fund are undocumented people or people without health insurance for some reason who need help with procedure costs and those who need the abortion pill and are not in their home province. We have another fund that we use to cover those costs, called the Norma Scarborough Emergency Fund and it is entirely funded through individual donations.

Are there other potential extra costs on top of travel?

There are all sorts of situations where people find themselves without insurance and no way to pay for an abortion, like not having health insurance or being out of province. And these procedures can cost between $500 to 3000, depending on where you’re getting it.

Plus, there’s the emotional and time burden. People have to figure out what to do by themselves. For example, say you needed a medical procedure because you have a heart murmur, you’d get a pathway to the service from your doctor. But when people need an abortion, in most cases, people have to go home, figure out where to go, wade through disinformation, and find a clinic. And then they have to make their way to that clinic themselves on their own dime.

Has the abortion pill made abortions more accessible, particularly for people in remote places?

In 2015, Health Canada approved the medication abortion, the gold standard from the World Health Organization that has been in use for over 30 years in 60 countries. So it’s new to Canada, but it’s not new at all. It’s finally easier to get abortion care outside of urban centres.

In most provinces, primary care providers can prescribe it. And the pandemic accelerated the process of doctors finally seeing the benefit of offering telemedicine. Now we have no-touch abortions, which means you can talk to your doctor from your home on Zoom, the prescription for the abortion pill can be faxed to the pharmacy, and then you can go pick it up and have your abortion managed at home. But it’s not always that easy. Some practitioners refuse to provide care on the basis of their own personal beliefs.

What can you do if your doctor won’t prescribe the abortion pill?

In those cases, you will have to find a public abortion provider (working from an abortion clinic, a hospital, or some health care center where primary care providers see the public). In some provinces, people can access an appointment for a medical abortion through telemedicine, which means that they can access it without having to travel outside of their community. This is what should be the case everywhere.

For more information or to find an abortion clinic, visit actioncanadashr.org.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Next: Women’s Health Collective Canada Is Addressing the Gap in Women’s Health