Maryam Faiz’s path to neuroscience wasn’t exactly a straight one. She considered architecture. She flirted with urban planning. She took a summer off from her PhD to intern at the BBC and spent another summer in Croatia tracking dolphins across the Adriatic. But a fascination with stem cells—and a meeting in Sweden with one of Canada’s leading experts in regenerative medicine—finally drew her to the lab. “When you see a neuron, it’s almost like space—you don’t know exactly what it is, but it’s just so beautiful,” says Faiz, a professor at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine. “There’s a feeling of unmitigated possibility.”

Her research now focuses on a promising class of star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes. “They’re a kind of glial cell, because glia is Greek for glue, and astrocytes were historically thought of as the sticky stuff that held the neurons of the brain together,” Faiz says. Whoops: Turns out scientists were selling astrocytes short. They actually play a huge role in the brain’s circuitry, regulating blood flow and controlling how information travels across the brain. Not only that—as Faiz and her team are learning, astrocytes may also be harnessed for brain repair, offering the future possibility of custom-made therapeutics for people suffering from neurological injuries and diseases. “Astrocytes are quite hot at the moment, in terms of things to study in neuroscience,” she says with a laugh.

(Related: The Secret to Learning a New Skill at Any Age)

What can go wrong with our brains?

Lots. Broadly speaking, the brain is not a regenerative organ, like the skin or even the liver. You don’t generally regenerate neurons—they’re kind of fixed. So you can have changes in the way the brain develops, and that can lead to neurodevelopmental disorders. You can have an injury, like a stroke, and lose neuronal cells. And then there are neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, where your neurons become under attack and start to die off.

When we lose these neurons, what impact does it have?

I can give you a personal example. My younger sister had a traumatic brain injury, and she lost neurons in a region of the brain that’s important for verbal communication. It was a small injury, and she was able to recover—because even though you lose neurons, the neurons around them can reconnect, which we broadly refer to as neuroplasticity. But my sister still has problems with speaking. The word school is problematic for her, because she can’t connect the sounds to the letters, so she’ll say shul.

The human brain is so interesting because it has this innate ability to rewire, kind of like an electrical circuit. But even small changes in neuronal loss can lead to pretty big impairments in function. And so depending on the region of the brain, you can have different types of impairments, whether that be vision or motor or cognition.

How does your work help with these sorts of impairments?

My lab studies astrocytes, which are really important for proper brain function: They fine-tune neuronal information, so they can make that information transmit further, or they can dampen it down. But after injury or disease, some types of astrocytes can become pathological and even start to kill neurons. One example was work out of Harvard on progressive multiple sclerosis—and this was preclinical, in mice, not in humans. It showed that if you just removed astrocytes in this end stage, you got improved function.

What we want to do in my lab is create new cells. Basically, you can take any mature cell and hit it with a bunch of genes that are important for its conversion to a new cell type. And so we started by reprogramming astrocytes into neurons. Again, this is preclinical—nothing to do with humans—but in mice after stroke, reprogramming improved mobility and gait to the level of an uninjured animal.

So you can transform the astrocytes that limit brain recovery into cells that are helpful instead?

I think the only way that reprogramming will work is if we’re able to generate really specific therapeutics. And that’s where it’s important to understand the role that different astrocytes play in different types of diseases at different points in that disease. Imagine a scenario where we’ve identified Astrocyte Type A15, which happens at a certain time post-stroke and is really deleterious. We could go in, target it, change it into another type of cell and leave all the other cells that are important for recovery.

Are there different factors that influence how astrocytes respond to injury or disease?

Over the last couple of years—this is so exciting—there’s been a clear link between the gut and the brain. We know that the bacteria that colonize your gut are really important in brain development, and also really important for neurodegenerative diseases and even injury. So after a stroke, for example, the bacteria in your gut gets altered. And we think this bacteria feeds back onto the brain and can affect the neuroimmune response. We have some really nice data—again, preclinical—that shows that just by using probiotics after stroke, it actually improves motor function. It’s wild. So one of the cool things we’ve started looking at is how different types of bacteria in the gut change the astrocyte response in the brain. We think that could be important for developing really novel therapeutics for brain treatment that you could administer in the gut.

It sounds like this is leading to more and more bespoke therapeutics.

That’s what our lab is all about. I think we’re in an era of personalized medicine. Especially in a system like the brain, which is so precise, you need to think about bespoke therapeutics. You’re not going to want to take out all astrocytes, which are so important, and you’re not going to want to put back all types of neurons. This allows us to be really specific.

And what are the benefits of such a specific approach?

I mean, we’re humans, right? There’s so much variation that there can never be a one-size-fits-all response. I think a lot of clinical trials and drugs have failed in that respect. Even if you just think about women’s health, 50 percent of our population was almost never tested. And so many of the drugs that have traditionally worked in men don’t work in women. Even if we could just conquer that, I think it would be amazing. But with personalized medicine, you start to make discoveries that are going to work no matter where you’re from, or what your background is, or your genetics or your sex or your age. That’s where the next 10 to 15 years are going to be really exciting.

Is that what keeps you motivated in your work?

Science tends to be quite incremental. But I do think, within 10 to 15 years, we could actually make a big difference with cellular reprogramming. And that helps us keep focused and on track to do the next experiment that’s going to take us to the next step that’s going to make the biggest difference in people’s lives.

Next: These Activities Help Prevent Dementia, According to a New Study

Dolphins speak. Elephants paint. Even spiders can manage to use tools. But humans do, in the end, have an edge over animals: We’ve developed a hugely efficient way to control our body temperature. Dogs pant to cool down. Seals pee on their flippers. All we have to do is sweat.

Here’s how it works: Humans have anywhere from 1.5 million to five million sweat glands distributed all over our bodies. As our temperature rises, our nervous system gets to work, stimulating those glands to release the salt water we have in our bodies, says Sarah Everts, the Ottawa-based author of The Joy of Sweat. “Our hot skin evaporates the sweat away from our body, which whisks the heat away,” she says. “This trick—evaporative cooling—is what dogs do when they pant. They’re evaporating water off their wet tongue. We can just do it over our entire bodies.”

(Related: Natural Deodorant Reviews: Which Ones Pass Our Sweat Test?)

Not all of us sweat the same way—on a hot August afternoon, certain people will be soaked through, while others, miraculously, will appear bone-dry. Everts explains that those lucky ducks are sweating so efficiently, at exactly the right rate, that their sweat manages to evaporate instantly. It’s still unclear exactly what’s responsible; it’s most likely a mix of genetics and where you grow up. “People are born with all their sweat glands, but they only become fully active within the first couple years of your life,” she says. “Researchers wonder if your climate then helps dictate the activity of those sweat glands.”

It’s not as though humans abhor all perspiration: Sweat lodge ceremonies are common around the world, and it can feel like a workout barely counts if we don’t break a sweat. “But then we spend $75 billion a year on products trying to pretend we don’t sweat at all,” Everts says. There’s still stigma attached to a sweaty handshake or dark patches blooming under a work shirt. Enough. “Sweating is a fantastic temperature-control system and one of the things that makes us human,” Everts says. “So I think we need to stop giving sweat the side eye.”

Next: A Sweaty Gal’s Guide to Sunscreen

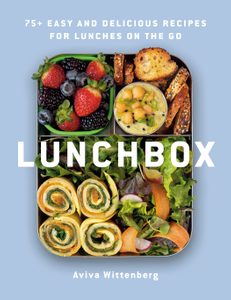

Juicy ripe figs are a magical sandwich or salad addition, but unless you live in a warm and sunny place, they can be hard to track down and extravagantly priced. I never turn down a basket of fresh figs when they are in season (and I drive home with them strapped in with the passenger-side seatbelt), but I count on dry figs for most of the year.

This fig and balsamic onion jam is a great condiment spread on a sandwich, baked into a pie, or served up on a cheese board, and it impressively comes together in less than 30 minutes with ordinary pantry ingredients.

Tip: This jam can be made ahead and stored in a tightly sealed airtight container in the fridge for up to 1 week.

Fig & Balsamic Onion Jam

Makes: 1 cup

Active Time: 10 minutes

Total Time: 30 minutes

Ingredients

- 2 Tbsp olive oil

- 1 small onion, diced

- ½ tsp salt Pepper

- 4 Tbsp balsamic vinegar

- 1 cup dried figs (see Note), stemmed and halved

- ½ cup water

Note: Use 1 cup roughly diced shallots in place of the onions in this recipe for a slightly milder onion flavor. Any variety of dried fig will do the trick, but if you’ve recently won the lottery and can get your hands on some dried mission figs, use them to create the best version of this jam.

Directions

- In a medium saucepan over medium heat, heat the olive oil. When the oil begins to shimmer, add the onions, salt, and a few grinds of pepper. Cook, stirring occasionally, until the onions begin to brown at the corners—about 10 minutes. Add the balsamic vinegar and cook, stirring, for 1 minute to reduce slightly. Set aside to cool down.

- While the onions cool, put the figs and water in a small saucepan over medium-low heat. Bring to a simmer and allow to cook, partially covered with a lid, for about 15 minutes, until most of the liquid has been absorbed.

- Transfer the onion and balsamic mixture and the figs (including any liquid in the pan) to a blender or food processor and process until smooth—about 1 minute. Taste and add salt and pepper as needed. Allow to cool, then transfer to a tightly sealed airtight container.

Excerpted from Lunchbox by Aviva Wittenberg. Copyright © 2022 Aviva Wittenberg. Photography © 2022 Aviva Wittenberg. Published by Appetite by Random House®, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: Healthy Lunch Idea: Egg, Greens and Cheese Tortilla and a Fruit Salad

Your hip flexors are the all-important muscles in front of your hips, around your groin. They’re part of your pelvis and they are essential for movement, helping you pick up your legs so you can move forward. Your hip flexors are also integral to posture and core stability. The main hip flexors, the iliopsoas muscles, connect to the lumbar spine, travel through the pelvis and attach to the inside of your femur, near the hip joint. This makes your iliopsoas the only muscles that connect the upper and lower halves of your body.

Our hip flexors do a lot for us, so if we don’t stretch them and build their strength, the muscles get fatigued, tighten up and weaken over time. When we sit for too long (say, in front of a computer), the muscles become shortened, which can lead to tightness and pain in the groin and lower back areas. In fact, even if you’re outrageously active, you might still experience tightness in the hips: Repetitive motion (like cycling or running) can also cause hip tightness.

Weak glute muscles, caused by a lack of movement, may also be a culprit. “When your glute muscles are weak, your hip flexors take over and absorb the load,” says Surabhi Veitch, a Toronto-based physiotherapist. “Some of the contributing factors for tightness in the front of the hip is weakness in the back of it, in the glutes.”

Luckily, there are easy-to-do hip flexor stretches that can help relieve hip tightness, whether it’s from sitting or exercising. A simple, familiar one that you probably already know is a lunge. “This can be a low lunge [with hands] on the floor, with a pillow or pad under your knee for support,” says Veitch. Or, make it into a more upright lunge by resting your hands on a chair or bench if you can’t reach the floor while lunging. The goal with a lunge, she says, is to rest in that position, and not struggle to hold yourself up.

Knee hugs are another simple hip stretch, and, as a bonus, you can do this one in bed after a long day or when you first wake up. “For people who are really flexible, they might not feel much,” explains Veitch. “But if you have a lot of muscle tightness, just hugging one knee to your chest will cause you to feel tightness in the other, outstretched hip and get that nice stretch.” Veitch notes that knee hugs are especially good for elderly people or people with mobility difficulties, as it doesn’t involve getting down to the floor and getting back up.

But once you are down on the ground—or in bed—try a lying quad stretch. While this move stretches out your quads and legs, it also opens up the front of your hips. “You can do it in a standing position but doing it on your side takes some of the gravitational load off,” says Veitch. Lying on your side will help you relax your muscles (instead of tensing them to try to maintain balance on one foot), allowing you to fully focus on the hips and quads. “These [lying down] stretches are a great way to loosen up in the morning,” she says. “You’re already in bed, so why not do a couple hip stretches?”

Aside from stretching, taking breaks from sitting is really important, says Veitch. “Try getting up every hour or 30 minutes, whenever your body starts to feel stiff and gives you that sign to move,” she explains. “Getting up changes the position of the muscles, and walking promotes an extended or stretch position, which allows the hip flexors to be stretched through their full range of motion.” So even if you don’t have time to work through an entire stretching or exercise routine, getting some movement in, even if it’s just a walk around the house, can help loosen up your flexors and cut down on pain.

Ready to get started? Try these hip flexor stretches:

Lunge

With one knee on the ground, get into a lunge position. Then squeeze your bum and push your hips forward to get a nice stretch in the front of one hip. Switch sides. Create more sensation by raising the arm on the side of your lowered knee.

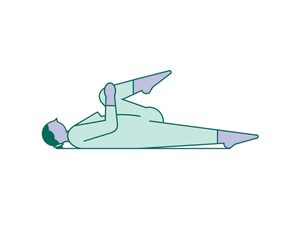

Knee hugs

Lying down, raise one knee to your chest and stretch the other leg out. Hug your knee to your chest and feel the stretch on the extended hip. Keep your extended leg glued to the floor/bed. If it lifts, lessen the hug on the bent knee. Switch sides. If you’re on a bed, you can leverage gravity for a deeper stretch: Dangle your straight leg over the bed and let the weight of it pull your hip out.

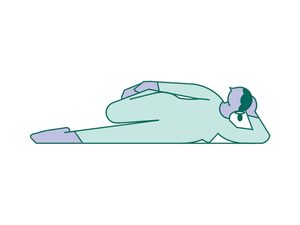

Lying quad stretch

Lie down on your side. Then, reach your top leg back, grab onto your ankle and pull it toward your bum (imagine you’re doing a quad stretch, but horizontal). Switch sides.

Next: 3 Moves to Stretch and Strengthen Your Glutes After Sitting All Day

An immersion blender, also called a hand blender, is a super versatile kitchen gadget. It’s called an immersion blender because you literally immerse its blades right into whatever needs blending—no need to transfer ingredients into another container, no need to find counterspace for a fancy blender or stand mixer.

And while it can beat a batter or purée a soup like nobody’s business, there are other surprising things you can do:

- Make the best scrambled eggs: Instead of whisking your eggs, hit them with an immersion blender for 30 seconds before they go into the pan: The air you get into them will result in extremely creamy scrambled eggs.

- Try DIY mayo: Throw an egg, a little mustard and lemon juice, some grated garlic and vegetable oil into a mason jar just slightly bigger than the head of the blender, and let it rip till emulsified. Voila: two-minute mayonnaise.

- Make homemade juice: Remove the skin and pith from an orange (or six) and chuck what’s left into a jar. Blend it up until you get perfectly pulpy orange juice.

- Make homemade pasta sauce: Crush whole tomatoes right in their can for incredibly easy tomato sauce.

- Give your nut butter new life: Blend back together natural peanut butter that’s separated in its jar.

KitchenAid Variable Speed Corded Hand Blender, $110, thebay.com

Next: This Toaster Oven Will Make You a Better Cook

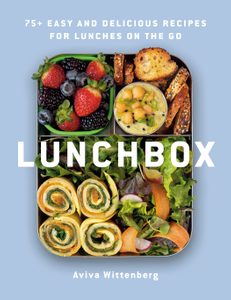

This quick and easy egg (or plant-based egg) and tortilla rollup is equally tasty warm out of the pan or sliced up and packed in a lunchbox. Don’t hesitate to play around with the filling based on what you have in the fridge. More often than not, I grate up odds and ends from my cheese drawer and throw in a handful of greens that are a bit too wilted to eat raw but are perfectly good to eat warmed.

Tip: This quick and easy recipe is best made the day of, but luckily it can be quickly thrown together between sips of coffee and bites of breakfast.

Egg, Greens & Cheese Tortilla

Makes: 2 servings

Active Time: 10 minutes

Total Time: 10 minutes

Ingredients

- 2 tsp butter

- 4 eggs, lightly beaten with a pinch of salt

- 2 large (8- to 10-inch) flour tortillas

- 2 handfuls baby spinach

- ½ cup shredded gruyère or any other hard cheese that melts nicely

Directions

- Make the tortillas one at a time. In a medium nonstick pan over medium heat, melt half of the butter. Add half of the beaten eggs and immediately top with a tortilla, pressing it down gently so that some of the egg flows up and over the top side of the tortilla.

- Cook for 1 minute and then top with half of the spinach and cheese. Cover the pan and cook for 2 more minutes, until the greens have wilted and the cheese has melted.

- Next, either fold the eggy tortilla up in the pan, the way you would an omelet, and pack for lunch as is, or slide it out onto the cutting board and allow it to cool for a few minutes. Repeat the process for the second tortilla. Once cool, roll up the tortillas, and slice into pieces as needed to fit in your lunchbox.

Packing Tip: Pack the tortilla with your favorite condiment—like salsa, hot sauce, or ketchup—and add a side of roasted potatoes and some sweet berries to create that authentic brunch-for-lunch feeling.

Great for Kids: Slice the rolled tortilla into rounds and secure with some fun food picks to make this wholesome lunch a kid-friendly finger food.

Excerpted from Lunchbox by Aviva Wittenberg. Copyright © 2022 Aviva Wittenberg. Photography © 2022 Aviva Wittenberg. Published by Appetite by Random House®, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: 9 Healthy Sandwich Recipes to Pep Up Lunchtime

It’s been about nine months since the Omicron variant arrived in the country and Canadians were lining up for COVID shot number three. We got boosted (or at least 56 percent of us over the age of 12 did), we were more diligent about wearing masks and social distancing, and the number of infections decreased right in time for summer. But now, provinces in Canada are reporting a new wave of infections, this time driven by Omicron’s highly contagious BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants. In response, provinces are offering fourth doses of the COVID vaccine to certain population groups.

We spoke to Dr. Horacio Bach, a clinical assistant professor at the University of British Columbia’s division of infectious diseases, and Dr. Dawn Bowdish, a professor of medicine at McMaster University and the Canada Research Chair in Ageing and Immunity, to learn more.

Who is eligible for a fourth dose?

If you’re in the 44 percent of the population over the age of 12 who hasn’t gotten their booster (a.k.a. the third dose), experts advise doing so now. It’ll help keep you protected as the country goes through the new wave.

As for the fourth dose, eligibility varies from province to province. In Ontario, Quebec, Yukon, Nunavut, Alberta and New Brunswick, anyone over the age of 18 is eligible for their fourth dose. In PEI, anyone over the age of 12 is eligible. In British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador and the Northwest Territories, only people in vulnerable groups such as seniors, those with compromised immune systems and those living in group settings are eligible to receive their fourth dose.

Did you recently receive your third dose? Some provinces require at least three months between your third and fourth dose, while other provinces require six. A recent COVID infection will also prevent you from getting another shot: Most provinces require that you be three months post-infection before rolling up your sleeves.

Why are some provinces allowing the general population to get fourth doses and some aren’t?

“There are two philosophies around who should get vaccinated and when,” says Bowdish. Public health agencies in some provinces believe only those who are at a high risk of getting seriously ill, such as older adults and immunocompromised people, need a fourth dose. Others believe vaccinating the general public can reduce the total amount of infections and prevent infections from reaching vulnerable communities.

Are fourth doses effective, particularly against Omicron?

“The vaccine we are using is based on the first COVID-19 virus,” Bach says, “but, the virus has gone through several rounds of evolution.” So the vaccine isn’t as protective against the newer variant, Omicron, and its subvariants.

A recent study from the CDC found that fourth doses were 80 percent effective against severe illness from Omicron. Although the newer BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants that are driving the current wave of cases in Canada weren’t part of this study, Bowdish says a fourth dose is indeed effective at reducing infections. But, there’s a catch: “It’s time limited,” she says. “You get only three months of really good protection and then it starts to wane.”

What if you’ve already had COVID—when should you consider a fourth dose?

Both Bach and Bowdish say it’s unclear exactly how long immunity from a COVID infection lasts, and BA.5 is good at dodging the immune system.

Bowdish recommends that people who’ve recently had COVID (within the last three months) wait to get their fourth dose. The antibodies their body produced to fight the virus when they were sick can help keep them protected until they get another dose, which would provide an additional three to six months of protection, she says. All provinces advise waiting about three months before getting their next dose.

Are there any risks to getting another dose?

Bowdish and Bach agree there are no downsides to getting a fourth dose. “While there’s been some worry we’re boosting too much, that’s actually a misconception,” says Bowdish. “There’s no evidence in the history of vaccination of that ever happening.”

And, while earlier concerns around vaccine supply might’ve prompted people to worry about jumping the “vaccine line,” we’re no longer in a situation where the demand for vaccines is outpacing supply—there’s enough for everyone who wants one.

What’s this I hear about the Omicron-specific vaccine? Is it worth waiting for?

mRNA vaccines, which are the type of COVID vaccine that most of us already have, can be tweaked to target the Omicron variant. Currently, Pfizer and Moderna are both testing retooled versions of their vaccines to include the Omicron variant and are on track to be ready by the fall. But it could be as late as December.

Bowdish says instead of waiting, we should consider getting another dose three to six months after our last booster or infection.

What else should people consider when thinking about getting their fourth dose?

If there’s some big event or trip coming up, Bowdish recommends getting a vaccine two weeks before you leave. “That’s a pretty good insurance policy to ensure that your trip isn’t disrupted by being ill.”

Next:What You Need to Know About COVID Vaccines for Kids 5-11

Sarah Cleyn sometimes jokes that while she was in utero her mother, Maureen Farnand, used to whisper a mantra to her expanding belly: be a nurse…be a nurse…be a nurse. “I was born with the idea,” says Sarah, a 35-year-old palliative care nurse in Ottawa. “I’ve just always known what I was going to do.”

To be fair, nursing is a family calling: Sarah’s two sisters as well as her aunt, Annette Ashe, are also nurses, and her mom worked as a nurse from the late 1970s until she retired six years ago. Maureen chose the path in part through the encouragement of her own mother, who she believes “had probably always wanted to be a nurse. She had eight children, and I was her right-hand person.”

Maureen graduated from the University of Ottawa in 1976 with a Bachelor of Science in nursing (at the time, most nurses did their training through hospitals). She started out in orthopedics, moved into a post-cardiac ICU ward, held a day job in an outpatient clinic, supervised personal support workers as a community-health nurse, had a stint in a church and wrapped up her working life as a faculty advisor in the University of Ottawa nursing program.

For Maureen, the opportunity to balance career and family was a major draw of the job. “I have five children, and nursing meant I could contribute to our financial stability and also be an example for my daughters—that being a working mother is possible,” she says. She was grateful for the practical flexibility her career provided: she worked part time when Sarah was young, took time off when daughters Meghan and Mary (now an ICU nurse and an oncology nurse, respectively) came along, and then returned to community nursing as a parish nurse, a role that was outside the grind of shift work and so allowed her to be present for her kids.

That example was huge for Sarah, not only in terms of balance, but also in witnessing her mother’s pride, confidence, and competence. “It made me feel like I could take on the world,” she says. Being a nurse wasn’t just something her mother did at work: “She was a nurse in every aspect of her life, including in her mothering. She was kind and caring and supportive, but firm.” When Maureen visited Sarah’s elementary school to teach students about prenatal development, “watching her in action stirred a passion in me,” Sarah says. “I wanted to be like that!”

This translated into endless games of hospital, during which “Nurse Sarah” would tend to friends, schoolmates, and siblings—often taking accurate blood-pressure readings and checking heart rates with her mother’s gear. The middle child of five, Sarah was a natural caretaker and peacekeeper, and she eagerly took on the responsibility of looking out for Mary, six years her junior and the littlest in the family. (“Some might call it bossy,” Sarah says, “but I call it leadership!”) In her teens, a job as a lifeguard highlighted a knack for keeping her cool in chaotic situations; in the end, lifeguarding paid her way through nursing school at the University of Ottawa.

While Mary and Meghan first explored other areas at university, each was drawn into nursing about two years in: They both looked up to their mom and sister, and the clearest professional path seemed to be the one their family had already carved out. Sarah also married into a nursing family—her mother-in-law, Mary Pat Cleyn, was an RN until she retired around eight years ago, while her sister-in-law, Liz Cleyn, is a nurse in the internal medicine department at the Ottawa Hospital. The family has found it pretty handy that every group dinner is an opportunity to spitball ideas with an informal panel of nurses: They can share intel and support each other through the most inside-baseball (or inside-hospital) conundrums. But it also means that, for this crew, there’s really no separation between work and life.

Given all this exposure, Sarah had a solid sense of what she was in for when she chose her profession. “I knew I would be taking the good with the bad, that some days I would be run off my feet,” she says. But she believed her passion for nursing and her connection to her patients would outweigh any issues with staffing and pay. Instead, over the 14 years since she started out, the negatives have become amplified. Compared to her mom’s day, working in hospitals now means debilitating burnout, 12-plus-hour ER wait times, cancelled surgeries, and hostility toward health care workers. “Nursing has thrown me for a loop,” Sarah says. And though she and her sisters were raised to believe that this is their calling, they’ve also felt their frustration start to grow.

The tricky thing with a calling, Sarah says, “is that it almost validates the notion that you have to do this because you’re meant to do this.” But nursing is still a job. And you shouldn’t have to sacrifice your well-being for the sake of—maybe—making rent. It seems that this realization is sweeping the field: Nearly one in four Canadian nurses intend to quit in the next three years. As Sarah surveys a system on the brink of collapse, she finds herself questioning what lies ahead. “Nursing has always been about emptying your bucket more than you get it filled,” she says. “But now it’s like they’re asking for drops that just aren’t there.”

In 1966, a decade before Maureen graduated from nursing school, Canada introduced federal socialized health care. In short order, nursing underwent a significant shift in both responsibilities and public perception, with more emphasis on specialization and medicalization, rather than simply providing care. As the demand for nurses—and the demands on those nurses—across the country intensified, a labour movement began to organize. Although ad hoc collectives had existed within nursing since the 1940s, it wasn’t until the early ’70s that formal coalitions like the Ontario Nurses’ Association developed. In 1973, the Supreme Court of Canada established a precedent for nurses to form collective provincial bargaining units across the country.

In theory, the rise of organized labour meant that nurses could team up to advocate for better conditions, fair pay, and reasonable hours. And over the next two decades, nurses across the country did fight to improve their working environments. But then the early-’90s recession hit, leading provincial governments to reassess their budgets and put social services—including health care—through the austerity wringer. In Ontario, massive layoffs and hospital cutbacks meant that thousands of nurses were left jobless.

Michelle Johnson, a senior nurse at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, has been watching the infrastructure erode since that recession. After Mike Harris became Ontario’s premier in 1995, “he decimated health care,” Johnson says. “He compared laid-off nurses to hula-hoop makers—he called us obsolete and said we needed to retrain so that we could do jobs that were relevant.” Subsequent Liberal governments made further devastating reductions. In Johnson’s 32 years of nursing, she says, “we haven’t actually ever had a significant raise.”

Bill 124 has worsened an already untenable situation for nurses in Ontario. That’s the legislation, brought by Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government in 2019, that limits wage increases for public-sector employees to no more than one percent annually over a three-year period. In many cases, this financial disincentive made it even less attractive for nurses to stay put in a foundering system. It compounded staffing issues and burnout in public health care at a particularly terrible time: Not even a year after Bill 124 passed, we were suddenly in a global pandemic.

COVID ratcheted up tensions in Sarah’s family as well. They especially fretted about Meghan, who had been working in the Ottawa Hospital ICU for less than a year when beds started to fill up with COVID patients. While ICU nursing felt like a “natural progression in my career,” Meghan says, she initially struggled with the stress and stakes of the job. “I feared I’d make mistakes, that I wouldn’t be smart enough or strong enough to endure the shifts.” Seven months in, she had just found her footing. But when the pandemic hit, “the fear, the doubt, and the stress all came crashing back.”

Meghan was rattled by both the volume of patients and the terrifying uncertainty of how to treat them and prevent transmission—especially early on, when PPE shortages meant she and her colleagues were stuck reusing their N95 masks. The worst part, she says, was the unknown: “Walking into work every day, not knowing what to expect.” She remains haunted by the final call she helped a young patient place to his wife, before she intubated him and put him on a ventilator. “It was unimaginable to think of this happening to my own family members,” she says.

As Maureen tried to comfort Meghan, who frequently called her in tears, she also worried about her daughters being exposed to something unknown. “I remember having gone through HIV, not knowing what that was. And then SARS—a couple of nurses died from that.” Despite that uncertainty, one of the hardest challenges that Sarah was facing was not volunteering to be on the front lines. With great difficulty, she prioritized the needs of her family, taking time off to be home with her kids, who are now eight, six, and four. But it’s a decision she still feels conflicted about. “It was a global pandemic. My skills were needed, and I felt I should be in there.”

While Mary’s position in an oncology clinic meant that she wasn’t directly caring for COVID patients, she nevertheless struggled to support people who, due to precautions, had no family or friends with them as they faced treatment—or even terminal diagnoses, which often came as a surprise because initial appointments were significantly delayed by the pandemic. The impact of these experiences hits her in waves. “As a nurse, no matter what your schedule is, there are shared difficulties that come with the heaviness of our roles. I’ve had to take a good amount of time outside of work to process these situations.” Most work environments, she adds, don’t expose people to the barrage of suffering, serious illness, and poverty that health care workers encounter on a daily basis.

According to Statistics Canada, there were 126,000 vacancies in the health care and social assistance sector, including registered and psychiatric nurses, in the last quarter of 2021—twice as many as in 2019, and a number that is only increasing as burnout, early retirement and the promise of better private-sector wages compel others to leave the field. Among all health care workers, nurses have reported the greatest declines in their mental health during the pandemic. (In another Statistics Canada survey, 37 percent of nurses described their mental health as “fair or poor,” compared to 27 percent of physicians.)

COVID has also made health care workers targets for people whose frustration with pandemic restrictions and requirements has coalesced into rage. Michelle Johnson notes that she and her colleagues have become alarmingly adept at calling security to manage angry patients and their family members. In three decades of nursing, she says, she’s never encountered this kind of hostility.

Media coverage of anti-vaccine protestors outside hospitals may have raised broader awareness of these conflicts, but that hasn’t translated into an increase in meaningful support on an institutional level. When the College of Nurses of Ontario (the field’s key regulatory body) shared the results of that StatsCan survey in a blog post, it threw in a few general resources: a link to crisis training, a mention of Employee Assistance Programs, and something called a “Self-Care Fact Sheet.” (It included suggestions like “improve work-life balance” or making dietary and activity-level changes “to help cope with stress.”) Sarah isn’t surprised by these bare-bones offerings. “I’ve never had anyone ask me, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’” she says. Even now, more than two years into the pandemic, there’s only minimal access to counselling available, despite the fact that nurses like Sarah and her colleagues are constantly dealing with death in a very real way.

“We’re in the middle of a global health crisis,” Johnson says. “Nurses can get a job anywhere. They’re offering massive incentives in the States. And here, we’re doing nothing.” There are supposed to be 50 full-time nursing staff on her unit; on average, they’re losing three a month. “We’ve lost well over half our full-time staff,” Johnson says. “They’re not coming back.” And there aren’t nearly enough bodies to cover for them. “Ontario graduates about 4,000 nurses a year. And right now, we’re roughly 30,000 nurses short.”

Because additional paid sick days, by some estimates, can amount to almost a half-percent salary bump—which, over three years, could easily push any “raise” past the 1 percent annual cut-off imposed by Bill 124—expanding leave for nurses is not an option, meaning they’re stuck taking unpaid sick days or working while ill. Which is to say: We’re treating the people who’ve been on the health care front lines throughout the pandemic—the ones who’ve inspired us to bang pots, make signs, and deliver pizzas for sustenance—as though they’re expendable, at a time when society needs them the most.

The effects of Bill 124 have become even more crushing as the cost of living has ballooned. In June of 2022, Canada’s annual inflation rate hit 8.1 percent, the highest it’s been since 1983. In practical terms, that means you’d need about $45 today to buy what you could have purchased with $40 in 2019—so a nurse whose salary has remained the same over that period is being paid less now, in relative terms. “Being praised can be helpful for job satisfaction and morale,” Mary says. “But when it comes down to it, how is value placed on our work? It’s in our status and in our salary.”

Since graduating a decade and a half ago, Sarah has worked as a nurse in many areas, from internal medicine to a stint in the ICU to her current palliative role. At no point has she worked on a unit that has been fully staffed. Sure, she says, she and her peers do what they can to find creative ways around their limitations. But it’s exhausting—and for Sarah, a mother of three young kids, taking on ever-expanding shifts to cover staff shortages isn’t feasible.

Sarah admits that she’s had moments where she’s toyed with the idea of finding a new job in a different field. Her sisters have wrestled with similar feelings. At times, Mary has seriously questioned why she remains in nursing. “There are massive learning curves that can often feel insurmountable,” she says. Early in her career, Mary was struck by a patient and sustained a concussion; the violence led her to search for a role that didn’t involve bedside care. “It sometimes seems illogical to stay in this incredibly challenging job when I could earn more for much less effort,” she says.

For Sarah, finding a sustainable way to be a nurse may mean moving away from the hands-on care that first drew her to the field and taking on a new role—one that could provide the sort of leadership and advocacy the profession sorely needs. After a recent promotion, she has become the advanced practice nurse for her team, which means she’s now a manager. She has a true passion for palliative care—it’s fulfilling, she says, to help patients navigate terminal illnesses, and to provide direct bereavement support to families—and she’s worried about moving away from that work as she assumes the obligations that come with a leadership role.

Yet, Sarah says she feels hopeful about the change she can make in this position. In her mom’s day, nurses put down their heads and did whatever it took to get the job done. From Sarah’s perspective, that’s no longer possible today. She wants to break down barriers between different departments so nurses can share information and make their jobs more efficient. She wants to fight for equal pay. She wants to empower nurses to access further education. She wants to push for cultural competence training, so nurses can provide end-of-life care to patients whose values and beliefs lie outside of Judeo-Christian traditions. She wants to advocate for a greater focus on wellness. “The last six months is probably the first time that I’ve heard colleagues even talking about their mental health, which is wild,” she says. “You’d think, especially in palliative care, that we’d debrief, but we never talk about how we’re doing as people.”

Sarah knows she can’t fix a broken system overnight. But as someone who gets what it’s like in the trenches—and who now has more power and autonomy—she can improve the work life of the people around her.

“I can’t in my heart of hearts leave nursing without knowing that I did everything that I could to make it better not just for myself, but for everyone else,” she says. And Sarah has faith that change is possible. She sees it in newer nurses, who have more confidence to stand up for themselves. She believes the pandemic has given the public a better understanding of how valuable nursing is as a profession. She can feel a culture shift on the horizon. She’d even like her kids to take up the family calling, she says: “I would be proud to watch them become nurses and carry on this amazing legacy.”

Next: I Need You to Know that Good Relationships Are Vital to Good Health Care

So you think toaster ovens do what…toast bread? Today’s versions do so (so!) much more. Just consider the undisputed star of the toaster oven line-up, which has rightfully pulled “toaster” out of its name and replaced it with “smart.”

Breville’s countertop Smart Oven can do everything your standalone oven can do, and arguably better. Aside from toasting bread (of which it can fire up to six slices) and reheating foods (ta-ta, soggy microwaved goods), it can:

- Roast and grill anything: It scans food and identifies where heat is needed most for a perfectly-cooked result (it’s smart, I told you). That means it gives chicken, beef, fish and veggies a delectable crispy outside and succulent inside.

- Bake bread, cookies, cakes and pies: The convection setting bakes goods so that they’re golden and crispy where you need it, soft and gooey where you want it.

- Cook a pizza: Consider this your new pizza oven. It comes with a 12″ non-stick pan to cook your pie (be it thin-, medium- or thick-crust) just the way you like it.

- Make French fries: This model has the added bonus of also being an air fryer. You can make fried foods (like French fries) that are a touch healthier than their deep-fried counterparts, since an air fryer cooks food with only a splash of oil.

But here’s the thing: The real reason this Smart Oven earns our praise (and hundreds of five-star reviews) is because it’s not only able to do it all, but it’s able to do it all well—and easily. There’s no fiddling with oven rack heights or worrying about over- or under-cooking your food since that’s the “smart” function is all about. Instead, just press one of the buttons plainly labelled “roast,” “warm,” or even easier, “cookies”, slide in your broccoli casserole, leftover pizza or chocolate chip cookies, and walk away. When it dings, it’s done. And you look like the experienced, effortless chef you never knew you could be.

Breville The Smart Oven Air Fryer BOV860, $424, thebay.com

Next: 3 Easy Ways to Be Healthier in the Kitchen, According to Science

It’s rare that a style comes along that’s both trendy and comfortable. Like the uber-functionable fanny pack that has also seen a recent resurgence, comfy ugly-chic “dad sneakers” are all the rage today. Stylish TikTok teens tout their chunky-soled sneaker finds in try-on hauls, while celebs like Dua Lipa and Bella Hadid have been photographed in shoes straight out of Jerry Seinfeld’s closet. The kids are onto something: These kicks—unlike high heels such as, say, stilettos—are much more comfortable and good for your feet.

According to Dr. Sujeet Gupta, president of the Manitoba Podiatry Association, chunky shoes have an advantage over flatter styles and ultra-high heels because they typically have some extra cushioning for the sole and added ankle support. He says, “You want the shoe to feel supportive around the ankle so you know that you won’t be excessively pronated or supinated.” Basically, that means that your weight won’t roll onto the inner or outer edges of your feet.

If an over-exaggerated sole just isn’t for you, you can still take advantage of fashion’s turn toward the functional by shopping for other comfy sneaker styles. The most important thing to look for when shopping for shoes is a “Cinderella” fit: Gupta says that finding the perfect size has solved many of his patients’ foot woes. “You don’t want too big of a shoe, because then your foot will slide back and forth, which causes friction, calluses and corns,” he says. A too-small fit, meanwhile, will cut off your circulation, or cause ingrown toenails, corns and more.

To find the perfect fit, advises Gupta, shoe-shoppers should first make sure there’s enough space in the toe box, which accounts for the front quarter of the shoe. “You always want to allow adequate room between the end of your longest toe and the front of the shoe,” he says, recommending about five-eighths of an inch as a guideline.

Then, consider the sole—opt for something that isn’t totally flat, since those shoes lack arch support, which helps your feet distribute your body weight evenly and avoids rolling your weight onto the edges of your feet. Gupta says he’s seen patients come in with ankle sprains and partial tendon thickening or tears from wearing flat skater-style sneakers, like Converse or Vans. “A lot of those skate shoes, in my opinion, are not the best, and they don’t have the support you want,” he says. “For people who swear by skate shoes, make sure you get a good insole to support your arches.”

Everyone’s feet are different, and while it seems like a no-brainer, the best way to find the perfect sneaker for you is by trying them on—which means making sure you can get to a shoe store IRL, instead of clicking “add to cart.” Once you’re in the store, finding a shoe that fits best may require checking out alternative sizes, like “wide” or “narrow” sizing, which are now offered by most mainstream shoe brands. “You don’t want a super wide shoe, or your feet will be swimming in it and you’re not going to get that support,” says Gupta. However, if a shoe is too narrow, it’ll constrict your feet and cut off blood circulation. On that note: Aim to go shoe shopping at the end of the day. After a few hours of walking and standing, your feet will be a little swollen, and your new shoes will be fitted to that size, which avoids the risk of buying shoes that will fit in the morning but be too tight by evening. As well, most people don’t have identical feet: Usually, one is ever-so-slightly bigger, so make sure you fit your sneaker to the larger foot. And don’t forget to wear socks when you try shoes on, preferably whatever you’d wear normally, not the paper-thin hosiery they offer you at the store.

Materials are also important to consider when shopping for shoes. Gupta suggests leather because it’s really durable. Plus, leather is breathable, easy to clean and always stylish. And major bonus: It conforms to your feet over time, leading to a custom fit. Canvas is another great option for an everyday sneaker. “It’s lightweight and easy to pull on right at a moment’s notice,” he says. Having some mesh in the shoe (like on the top) is especially ideal in the summer, when your feet need to breathe. If your feet are trapped in stuffy shoes all day, especially if they’re a snug fit, you’re more likely to end up with blisters or corns. Gupta also likes suede for sneakers, “because it’s naturally soft, cozy and warm, so it’s good for autumn and winter.” Synthetic materials like faux leather and PVC aren’t bad, but they might be less breathable.

In the end, it all depends on what you want out of the shoe. Do you want to be able to pull it on and head out the door quickly? Do you need a bit of warmth for your feet? Or maybe you need some air. All of this will determine the exact materials you pick.

And, of course, there’s personal style to consider. I, for one, love chunky soles. They look fantastic and, being all of five feet and two inches tall, I appreciate that they give me a slight height boost without wrecking my feet. I also love the literal bounce in my step that I get from all the extra material.

If you’re looking for a dose of nostalgia to go with your kicks, grabbing a pair of trendy dad sneakers will take you back to the pragmatic ’90s—comfort included. Plus, if the cyclical nature of fashion has taught us anything, these kicks will be just as hot 25 years from now as when you strap them on today.

(Related: How to Find Summer Sandals That Won’t Wreck Your Feet)

Try these

New Balance 574

New Balance is the original dad shoe—their funky colourways, thick soles and sleek designs have made their sneakers icons. This new design is a bit wider than the narrow silhouettes of previous generations, but still boasts a cushy sole, lightweight materials and a durable build.

$125, sportchek.ca

Steve Madden Possession Sneaker

These chunky bubble-gum-pink runners are the statement sole you need. With mesh for breathability and a molded insole, these shoes are both stylish and functionable.

$110, nordstrom.ca

Hoka Bondi 8

Hokas have become the “it” sneaker for runners, but they’re also great for everyday wear. The Bondi 8 has a chunky sole for maximum comfort as well as a memory-foam collar so your ankles will be perfectly supported, whether you’re out jogging

or walking to the coffee shop.

$200, hoka.com

Asics Gel-Nimbus 24

These sneaks feature a light heel, a pull-on tab and a mesh top for breathability. The latest version of this shoe is 10 grams lighter than the previous iteration, making it a great option for walking and running. This specific model comes in “wide” sizing for the perfect fit.

$210, sportchek.ca

Vessi Everyday Classic

Lightweight and waterproof, these designed-in-Vancouver sneakers are your new 24/7 shoes. Made with Vessi’s upgraded sole, the kicks have seamless, supportive movement so your feet stay happy all day long.

$135, ca.vessi.com