UPDATE, Nov. 8, 2023: Since this story was first published, the province of Ontario has revised its breast cancer screening guidelines to include mammograms for women who are age 40 or older (instead of age 50 or older). Starting in the fall of 2024, Ontario women over age 40 will be able to self-refer for a mammogram every two years, even if they are not considered high-risk for breast cancer.

Every morning, after completing her skincare regimen, Heather Campbell would rub her fingers in small circles around her breasts, feeling for any changes. On the morning of Friday, October 13, 2017, when she was 44, her fingers bumped against a hard bulge on the side of her left breast. Shocked, Campbell stopped, palpated the lump again and decided she’d wait a day before she worried. Breasts change all the time, she told herself. Then she headed to her downtown Calgary office, where she worked as a chemical engineer. The next morning, she checked her breast once more. The lump was still there.

On Monday, she called her doctor and got an urgent referral for a diagnostic mammogram. Campbell had never had a screening mammogram, which is the best way to detect breast cancer early and is known to reduce deaths from the disease. Canada’s national guidelines, last updated in 2018, recommend that women without a family history of breast cancer have mammograms every two to three years, starting at age 50. Campbell was not due to begin screening for another six years.

She remembers standing there, nervous and topless, with her breast squeezed between two plates. The mammogram was immediately followed by an ultrasound. Afterward, as Campbell sat in the screening room without a shirt or bra on, a radiologist came in and told her: We have concerns.

“I was like, what are you talking about? This is insane,” says Campbell. Cancer didn’t run in her family. She was four months into a dream job at AESO, Alberta’s electric system operator, working on their renewable electricity program. She was dating a man she liked, and she still hoped to have children. Campbell returned to her office, sat down in her cubicle and shook, whispering her worst fears into the phone as she spoke to a friend.

After that, everything moved quickly: a biopsy; a diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma, the most common type of breast cancer; then referrals to a surgeon, a medical oncologist, a chemotherapy support class and a fertility clinic.

Over the next six months, Campbell received a half-dozen rounds of chemotherapy, followed by a partial mastectomy that removed 45 percent of her left breast. Staff at the fertility clinic told her that, because of her age, her eggs could not be frozen. Because her breast cancer was estrogen positive—meaning the presence of the hormone in her body contributed to its spread—the medication used to stimulate her ovaries to harvest her eggs would have also stimulated her cancer, making it worse.

(Related: How to Do a Self Breast Exam)

In June 2018, she began a three-week regimen of daily radiation treatments, with Saturdays and Sundays off. To reduce her estrogen levels, she had a full hysterectomy and oophorectomy in July 2020.

Campbell believes that if she had been screened earlier, she would have been diagnosed at an earlier stage, and spared some of the painful treatments that left her scarred, infertile and too sick to continue at her job.

“If I had been screened at 40, I probably would have had a little lumpectomy. Maybe a radiation or two,” says Campbell. “I might have still had children.”

Campbell is one of many patients, researchers and physicians in Canada who are calling for earlier breast cancer screening for all women, but especially for Black women. Delays in screening may be particularly devastating among Black women, but no one can yet say so with certainty here in Canada. Unlike in the United States, Canada does not collect the race-based data that could demonstrate any heightened breast cancer risks for Black women.

But ample evidence from the U.S. shows that Black women are more likely than white women to be diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer at a young age, more likely to be diagnosed with cancer at an advanced stage and more likely to die at a young age from these cancers. Despite these patterns, Black women don’t have the same opportunities for screening, genetic testing, treatment and clinical trial participation as white women, U.S. studies show.

Without race-based data in Canada, there is no evidence to suggest Black women here experience similarly terrible outcomes. And, yet, there is also no evidence to show that they do not.

Aisha Lofters, a family physician and chair in implementation science at the Peter Gilgan Centre for Women’s Cancers at Toronto’s Women’s College Hospital, said she and her colleagues noticed that they were seeing many Black women with aggressive or advanced cancers in their 30s and 40s. These women found lumps on their own—accidentally or during self-exams—rather than by mammograms.

To Lofters, this pattern suggests something is wrong. “Sometimes the best evidence is people’s stories. It’s what they are telling you,” she says.

Lofters is cautious about applying American data to Canadian women. The two countries’ health and economic systems differ enormously, she points out. The populations are not comparable. The Black population in Canada is more diverse genetically than the Black population in the United States. Black women in Canada are more likely to have ancestral roots from throughout Africa, whereas Black women in the U.S. more often have ancestry that can be traced to West Africa, reflecting the deep history of people being taken from nations in that region and enslaved in the Americas.

Moreover, race is not biological, but is a social construct, says Lofters. This is an important distinction: Genetic predispositions to illnesses depend largely on ancestry—where someone’s roots are—and not race. Even so, she says, American research is sending a signal about breast cancer and Black women with West African ancestry that Canadians should not, and cannot, ignore. “We need to recognize that signal, get people aware of it and produce the best research,” she says.

(Related: The Forces That Shape Health Care for Black Women)

In the U.S., non-Hispanic Black women have a 45 percent higher risk for invasive cancers before age 50 than non-Hispanic white women. This study, which was published in the journal Cancer in 2021, found that Black women are more likely to die from breast cancer before they are 50. Another study that looked at nearly 200,000 women between the ages of 40 and 84 who had undergone a screening mammogram found that Black women have a nearly threefold risk for triple-negative breast cancer, one of the most aggressive subtypes.

As a result of this growing body of evidence, the American College of Radiology and Society of Breast Imaging updated their screening recommendations to highlight the heightened cancer risk for Black women and other women of colour. The organizations called for annual mammography screening beginning at age 40 for all women but noted that any delays in screening disproportionately harm women of colour.

In Canada, the national guidelines on cancer screening come from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, a committee set up by the Public Health Agency of Canada. The task force consists of 15 volunteers with expertise in primary care and disease prevention. In the most recent guidelines, from 2018, screening mammography for women in their 40s is not recommended. They made the case that the benefits did not outweigh the risks of overdiagnosis—picking up tumours that are unlikely to cause harm. Women aged 50 to 74 should be screened every two years, they said. The authors added a caveat for women in their 40s: Some may wish to be screened based on their values and preferences. “In this circumstance, care providers should engage in shared decision-making with women who express an interest in being screened,” they wrote. But in the studies used by the task force, few Black women were included (they relied heavily on data from Scandinavian countries). And the reality is that Black Canadian women have been diagnosed under the age of 50 after being told they are ineligible for screening mammography.

(Related: Women’s Health Collective Canada Is Addressing the Gap in Women’s Health)

Dawn Barker-Pierre was born in Barbados and moved to Toronto as a child. A mother of three, she wanted a mammogram when she turned 40. When she asked her family doctor, she was told she didn’t need it until age 50. Two years later, she asked again, but was told no a second time: She had no history of breast cancer in her direct family and she was healthy, with no lifestyle behaviours that would increase her risk.

Barker-Pierre had felt dismissed by her doctors before, however, with prior questions about health changes she’d noticed. The first was skin-colour changes under her eyes, which can be associated with thyroid issues, but when she asked for further tests, she was sent to a dermatologist. Eventually, she insisted on getting bloodwork, and persisted until her labs revealed she was suffering from hypothyroidism.

A few months later, at age 44, she discovered a lump in her breast one night while she was watching TV. Her doctor sent her for a mammogram. As the technician performed the scan, she told Barker-Pierre that the healthcare team would not be able to determine when things started changing in her breast because there were no previous scans in her records to compare against. “That floored me,” she recalls.

Barker-Pierre, whose youngest child was 12 at the time, was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, which is typically fast-growing and hard to treat. The cells in triple-negative breast cancer don’t have receptors for the hormones estrogen and progesterone, and they do not, generally, make large amounts of the HER2 protein. But most targeted therapies and medications (like tamoxifen or Herceptin) used in breast cancer treatment go after that protein or those hormone receptors. With triple-negative breast cancers, the main treatment options are chemotherapy, with its host of toxic consequences; surgery; and immunotherapy. Overall, “there are no targeted treatment options for what is a more aggressive cancer,” says Andrea Covelli, a surgical oncologist with Mount Sinai Health Network whose research is focused on health inequities.

Triple-negative breast cancer is more common in Black women, and this has been shown consistently in studies across different countries, says Juliet Daniel, a professor and cancer biologist at McMaster University. Daniel’s work is personal: Her mother died from ovarian cancer four days before Daniel’s undergraduate convocation from Queen’s University, and this came a few months after the death of a close family friend who had breast cancer. These losses shook Daniel, who had planned to pursue medical school. After finishing her bachelor’s degree, she decided she didn’t want to work in a hospital where she might be faced with patients dying of cancer because drugs had not yet been created to treat their disease. Instead, she became a cancer researcher, focused on solutions and treatments. Decades later, in 2009, she herself would face a breast cancer diagnosis.

In 1999, Daniel had discovered a gene that, later, she found was associated with a number of cancers, including triple-negative breast cancer. She named the gene Kaiso, after the West African music that inspired calypso, the musical genre that’s deeply ingrained in the culture of Barbados, Daniel’s birthplace. Over the last 20 years, Daniel has led groundbreaking research showing that Kaiso is highly expressed in the breast cancer tissues of Black women compared to Caucasian women, and that women with high levels of Kaiso expression are less likely to survive breast cancer.

Daniel believes there is more than enough evidence to begin screening women by age 40. “I would say that young Black women should be having a baseline mammogram at the age of 40 if possible,” she says, adding that she would like to see Canada’s national guideline changed to recommend a mammogram for all women at 40, as the risks of screening younger women (such as false positives that could result in needless biopsies or even surgery) are outweighed by the benefits. “The earlier breast cancer is diagnosed, the higher your probability of survival,” she says.

Changing the nationwide recommendations will only address one barrier affecting Black women in Canada when it comes to the prevention and treatment of breast cancer. There is evidence at the provincial level to show that Black women are dealing with multiple obstacles in the cancer care system. This can have deadly or life-altering consequences. In Ontario, research conducted by Lofters and her team has found that women who immigrated from the Caribbean and Latin America wait longer for a diagnosis, are diagnosed at later stages and have a longer interval from diagnosis to the start of chemotherapy for reasons that not well-understood. Another study showed that women in Canada who were born in a Muslim-majority country were less likely to have regular breast cancer screening. In Nova Scotia, Black women are less likely to get mammograms; Black women in that province also told researchers that they had difficulty navigating the health-care system, and that they faced racism from clinicians.

For Daniel, these findings come as no surprise. She often hears stories from women who feel doctors dismissed their concerns about cancer and told them they were too young for a mammogram. “That’s irresponsible,” says Daniel. “At a minimum, they should ask about family history and send those patients for an ultrasound rather than telling the patient they’re too young to have breast cancer.” In many ethnic communities, she notes, women can face a stigma after a cancer diagnosis. When women come in to ask about screening, they should be welcomed into the system rather than turned away, she says.

Daniel and Lofters both work with Olive Branch of Hope, a Toronto-based organization that raises awareness and supports Black women with breast cancer. They want more education among all women about the risks of breast cancer at all ages. They also want better training for physicians, including a designated course on equity, diversity and inclusion where doctors would be educated about cultural sensitivity, including “the challenges that non-white patients experience, and the damage and the hurt that causes to many non-white, equity-seeking, equity-deserving patients, regardless of disease,” says Daniel.

The Canadian task force says it will release an updated, nation-wide breast cancer screening guideline sometime early in 2023. In the meantime, several provinces have modified their policies and brought down the recommended age to begin screening—but whether this increases access for any one individual will depend on where she lives. In British Columbia, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, women in their 40s are encouraged to talk to their doctor, and are eligible for screening every two years. Alberta recently announced a new policy recommending regular mammograms beginning at age 45. All other provinces recommend that screening begin at 50 for women who do not have a family history of breast cancer.

Women of colour are also underrepresented in the research that helps set cancer treatment guidelines—a pattern that reflects, in part, a deep suspicion in the Black community that grew out of historic mistreatment by scientists, says Lofters. She urges women and men who are diagnosed with breast cancer to participate in clinical trials. If research is carried out on mostly white or racially homogeneous populations, “we’re not getting the diversity that we need among people in the trial, and then we don’t know truly how broadly applicable the findings are,” she says. Lofters, Daniel and Covelli are trying to address this in Canada by proactively seeking out Black women to participate in studies to learn about inequities in the system.

(Related: Incredible Black Women Who Are Changing Canadian Health Care)

In Calgary, Campbell is now almost five years out from her diagnosis. Her life looks very different today. She worked throughout her chemotherapy treatments, but found that the drugs left her unable to do basic math in her head, and she felt she could not perform at work in the way she wanted to. “Having to walk away from [my dream job] was almost as heartbreaking as the cancer,” she says. She took time off and returned to the workforce in a different role.

Campbell knows firsthand that disparities exist for Black women with breast cancer, and it goes beyond screenings, diagnoses and prognoses—it’s also a widespread failure to recognize that not all breast cancer patients have the same needs. When Campbell developed skin rashes and facial scars from her chemotherapy, she saw three dermatologists for help with her eczema. They said her concerns were not uncommon in Black patients, but they did not have an answer, she says. A fourth specialist reached out to a group of Black dermatologists who finally offered advice.

Nearly two years after her lumpectomy, Campbell went to a plastic surgeon to discuss breast reconstruction. As she looked through the catalogue with photos of breasts post-surgery, she did not see a single breast of a woman of colour. She couldn’t tell what the scars would look like her on skin. Campbell walked out. She eventually had two reconstruction surgeries, using a newer technique: autologous fat grafting, in which fat is removed from her abdomen and injected into the breast.

Campbell still feels frustrated that Canada does not collect the race-based data that could identify any disparities experienced by Black women with breast cancer. These gaps exist here, independent of socioeconomic status, she insists. In the absence of data, stories like hers are the best evidence we have.

“I’m not poor. I’m an engineer. My second degree is in law. I can read all the medical information quite fine. I even know how the drugs I use are made,” says Campbell. “So help me understand why I had such a miserable time with breast cancer. It has nothing to do with my poverty or access to medical care.”

Next: As a Cancer Journey Coach and Breast Cancer Survivor, I’m Changing the Narrative for Cancer

To start: Meet the not-so-secret ingredient

Have you heard of marine phytoplankton? This microscopic plant has been around for billions of years (2.5 billion, to be exact). It’s the foundation of oceanic life, a primary producer of nutrition in the food chain, responsible for 50 percent of the oxygen we breathe, outputs powerful antioxidants, and plays a critical role in the planet’s carbon cycle. It took 15 years of R&D – including 90,000 research reports and 1,300 clinical trials—but that powerful plant is available in one small daily pill, and here to help Canadians harness their youth.

But first: A bit more about the science

One of the biggest culprits in aging is oxidative stress – a process akin to a car rusting from the inside out. Stress, inflammation, pollutants and unhealthy dietary choices are among the millions of triggers that contribute to our body’s oxidative stress. Of course, we all know that antioxidants can help, but here’s what you don’t know: Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are the strongest enzyme against oxidative stress – and phytoplankton has more SODs than any other source out there. What’s more? Its bioavailability makes it easy for the body to absorb.

And now: The perfect little capsule.

The world’s number-one phytoplankton brand is based here in Canada. The revolutionary plant-based supplement, Karen Ageless, is not only among the greatest sources of this “magic” ingredient on the market, it’s also rich in vitamin C and supporting antioxidants. And if inquiring minds want to know, it’s vegan, gluten-free and cruelty-free.

But that’s not all! Karen Ageless also….

Karen Ageless does more than fight aging. It aids in energy production, weight management, physical recovery, acne reduction and collagen production. It’s good for clear skin and glossy hair, promotes tooth and gum health, strengthens bones and boosts the immune system. These benefits aren’t only backed by researchers, but independent reviewers, too!

What now? How to get your hands on it

Have Karen Ageless delivered right to your door! Subscribe today, and have a month’s worth of doses delivered every 30 days. Who knew ageless beauty could be so easy?

While menopause is a completely normal stage of life (Reminder: 10 million women in Canada are either in or entering perimenopause, menopause, or post menopause.), many women feel shame around it. In fact, some say when they lose their period, society makes them feel less valued as a woman—and that’s heartbreaking.

“Menopause is overwhelmingly viewed as negative and remains shrouded in secrecy,” says Janet Ko, president and co-founder of the Menopause Foundation of Canada. “This has a negative impact on women’s health and on society as a whole.”

According to a study by the Menopause Foundation of Canada, one in two women feel unprepared for this new life stage. What’s more, three in four women find its symptoms interfere with their daily life, and one in 10 leave the workforce due to unmanageable symptoms.

Menopause comes in three stages: perimenopause, menopause and post menopause. Perimenopause typically occurs between the ages of 40 and 55 and can last 4-10 years before experiencing a full stop to your menstrual cycle. During this period, estrogen and progesterone levels fluctuate, which can trigger some not-so-pleasant symptoms (looking at you, hot flashes!). Menopause occurs when ovaries stop producing eggs and a woman has been period-free for one full year. Post menopause begins immediately after menopause and doesn’t have an end date.

Perimenopause and menopause bring with them a slew of symptoms—over 30 of them, in fact. These can include, yes, hot flashes, but also heart palpitations, aches and pains, lack of energy, depression, insomnia, irregular or heavy periods and bladder control issues. Postmenopause can increase a woman’s risk of heart disease, osteoporosis and genitourinary ( symptoms include vaginal dryness, painful sex, urinary tract infections and general irritation of the genital area).

To eradicate stigma around menopause, Ko says we must address its root cause—which is ageism and sexism in our society. “There is education, support and open discussion for other natural phases of life, such as puberty and pregnancy, but when it comes to menopause there is a deafening silence,” says Ko. “We need to normalize what is a natural part of life.”

That’s why Always Discreet and Always are on a mission to help women re-gain their confidence and embrace menopause. The brands aim to empower women at all stages of life via their work on initiatives like #EndPeriodPoverty and Like a Girl and support women from their first period to their last—and beyond.

Always Discreet is also a proud supporter of the Menopause Foundation of Canada, whose goal is to break the silence and the stigma of menopause and to empower women with evidence-based information. “Menopause can usher in an exciting and vibrant phase of life,” says Ko, and people need to recognize that.

Incontinence affects 50 percent of women, during menopause and can negatively impact their physical, emotional and social well-being. Always Discreet offers a collection of liners, pads and underwear specifically designed to offer protection and support for bladder leaks and incontinence. And Always has a vast assortment of menstrual products, including pads and liners, designed to help manage any type of period. All products are particularly useful up to and including perimenopause, when menstrual flows can change, becoming heavier or irregular.

Through these initiatives, Always Discreet and Always hope to increase conversation around menopause to both educate and de-stigmatize the topic, so women can embrace this phase of life with confidence.

Shop Always Discreet and Always products to support your changing menstrual and bladder leak needs. Available at Walmart. For more resources about Menopause, please visit menopausefoundationcanada.ca

Adhesive capsulitis, better known as frozen shoulder, is an uncomfortable condition characterized by pain in the shoulder joints and restricted range of motion. “I like to describe it as bubble gum in your shoulder, and you’re trying to move but it takes so much effort to move past a certain point,” says Surabhi Veitch, a Toronto-based physiotherapist and owner of the Passionate Physio. This condition makes everyday tasks like scratching your back or grabbing something off an overhead shelf feel impossible.

Like the name implies, frozen shoulder comes with an unbearable “stuck” sensation. The bones, ligaments and tendons that make up the shoulder joint are encased in connective tissue—frozen shoulder occurs when the connective tissue thickens and tightens around the joint, restricting movement. Often, people develop frozen shoulder because they’re not moving the joint frequently, such as when they’re in recovery from a surgery or injury, though a sedentary lifestyle can also cause the painful condition. People aged 40 to 60, and particularly post-menopausal women (thanks to a change in hormone levels), are the most likely to develop frozen shoulder.

Treatment for frozen shoulder typically focuses on pain management, and doctors will often suggest anti-inflammatory medications like aspirin or ibuprofen. In addition, easing frozen shoulder pain requires stretching out the connective tissue and restoring the joint’s range of motion. Getting into the habit of stretching can also fight off other aches and pains and help improve flexibility. According to Veitch, a stretching routine in the middle of your workday, especially if you’re sitting at a desk, can help maintain good range of motion and prevent injury.

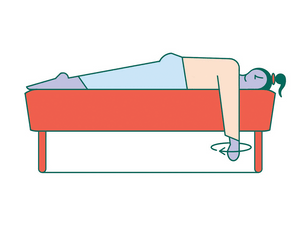

One of the best exercises to integrate into your daily routine is called the lying pendulum. “With frozen shoulder, your muscles will be stiff. This stretch can help you regain movement in the shoulder,” says Ivana Sy, a Vancouver-based kinesiologist. Sy says to start by lying face down on a bed or coach. Then, drape one arm over the edge and let it dangle. Then, slowly move the affected arm side to side and forward and backward and around in circles. Repeat three times daily. Do the exercise for 30 seconds and, over time, increase the duration up to five minutes as you progress. According to Sy, the pendulum can really help improve range of motion and reduce aches and pains.

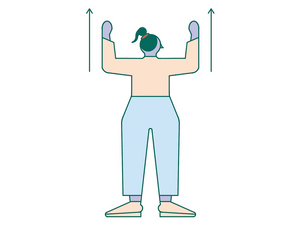

Veitch suggests using a wall to help stretch your shoulders. Start by facing a wall with your toes as close as possible to the baseboard. Then, place your hands at eye level and slowly creep them up the wall to create a stretch in your shoulder blades. Try to reach as high as you can!

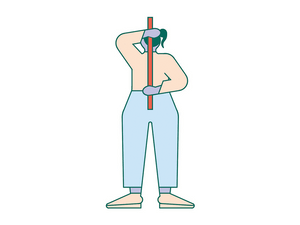

Regaining or maintaining the ability to reach behind you is also important. As we age and lose mobility, Veitch notes that reaching back often becomes a challenge, even without a condition like frozen shoulder. “Many people are struggling to put on their bras, and they flip it around to do their bra up in the front,” says Veitch. “But if we avoid the movement, it becomes more difficult.” Practise reaching behind your back by grabbing one end of a scarf (or any length of fabric) with one hand. Holding the scarf on one end, reach over your shoulder, as if to scratch the back of your neck, to dangle the scarf down your back. With your other hand, reach back as if you were going to grab something from your back pocket. Instead, grab onto the opposite end of the scarf. With your top hand, pull the scarf to gently slide your bottom hand up. Switch hands and repeat.

“With true frozen shoulder, it can take a long time, even with treatment, to feel better,” says Veitch. “But the goal with stretches is to maintain mobility so your entire life is easier.”

(Related: 4 Stretches to Improve Range of Motion as You Age)

Try these frozen shoulder exercises:

The pendulum

Lying face down on a bed or couch, let one arm hang off the edge and move it back and forth and side to side to increase range of motion. Repeat on the other side.

Wall slides

Facing a wall with your feet as close to the baseboard as possible, place your hands on the wall at eye level and slowly inch your fingers up. Try to reach as high as you can!

Reach around

Grab a scarf end with one hand and reach up and over your shoulder, with it dangling down behind you. With the other hand, reach back and grab the bottom of the scarf. With the hand on top, slowly pull on the scarf to get your bottom arm to move up. Switch hands and repeat.

Next: Your Phone Might Be Hurting Your Hand

When June Jones says she wakes up early most days, she means before-the-birds early. The retired grandmother of four is up before dawn (sometimes as early as 2 a.m.) several days a week for dialysis. She crawls out of bed and creeps down the hall to her spare bedroom, where she has a hemodialysis machine set up in her Ottawa home. Jones hooks up the chest catheter, lies down and starts a four-hour-long treatment. “I usually can’t sleep,” she says, “but I rest my eyes and listen to quiet music, or I read a book.”

Jones, who is 61, has become an expert at managing kidney disease and, over the past 33 years, she has tried almost every treatment available to her.

In the spring of 1989, a year after her son was born, she recalls feeling really run down, even for a busy young mother. Her doctor eventually sent her to a nephrologist, who diagnosed her with IgA nephropathy, a chronic kidney disease. Over the next decade, Jones was able to manage her condition with a range of medications— until 1998, when her kidneys failed. Six months later, she was fortunate to get a kidney transplant. “That worked really well for almost 15 years,” Jones says. Over time, though, the disease came back, and nine years ago the new kidney failed, too.

Since then, Jones has been on dialysis, waiting and hoping for another transplant. Unfortunately, it has proven extremely difficult to find a match due to her unusually high antibody levels.

For now, Jones is set on using her experience with the disease to help others. She volunteers with the Kidney Foundation of Canada’s peer support program, sharing advice with other patients. “People can get down about dialysis, but I say you can’t let it rule your life, because it will if you let it.” Jones works hard at keeping her own outlook bright, too. “If I wasn’t on dialysis, life would be so much better—but still, life is good,” she says.

Next: Everything You Don’t Know About Kidney Disease (But Should)

The kidneys are as vital to our health and well-being as the heart or lungs. But chances are you rarely give them a second thought—or even know how they work. “The kidneys are underappreciated in terms of all that they do,” says Caitlin Hesketh, a nephrologist at the Ottawa Hospital. They filter all of the blood in the body (at a rate of about one litre per minute), balancing minerals like potassium and sodium and removing waste products and excess water through urine. Kidneys also produce hormones that regulate blood pressure and red blood cell production, and they play a role in bone health, since they’re involved in manufacturing vitamin D and managing calcium and phosphate levels. This pair of vital organs, each about the size of a clenched fist, is reddish brown in colour and has a similar shape to its namesake legume, the kidney bean.

When kidneys fail

“There are about 4 million Canadians living with kidney disease,” says Amrita Sukhi, a nephrologist with Trillium Health Partners in Mississauga, Ontario. And many of them aren’t even aware they have renal failure because the symptoms (fatigue, peeing less often) are analogous with other diseases.

The term kidney disease describes an array of disorders and conditions, can range in severity from mild to severe and sometimes results in complete kidney failure (also called end-stage kidney disease). “When people have kidney failure, they may retain too much of that stuff that the kidneys should be getting rid of and that can make people very sick,” says Hesketh. But in the early stages, for the most part, the body compensates well for reduced kidney function. As with high blood pressure, kidney disease can go undetected, and many people only realize they have a problem once it’s quite advanced.

“It’s unfortunate, because people don’t tend to get really sick until the kidney function is down to five or 10 percent,” says Hesketh. Sukki adds, “By the time you get symptoms, which are vague, like poor energy, reduced appetite, some swelling, you can be on the brink of requiring dialysis.” (Dialysis is a medical treatment, often done in hospital several time a week, that cleans the blood and removes waste fluids from the body.) Without treatment, full kidney failure eventually leads to death.

That’s why routine screening for kidney problems is so important. The albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) test measures the amount of protein in urine, and flags high levels that could indicate possible kidney damage. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) blood test is another easy way to measure how well your kidneys are working. Either test can be done as part of a routine exam. Your doctor can determine your risk factors (more on that soon) and how often you should be screened.

Managing kidney disease

“A lot of patients come to the clinic very scared that I’m going to put them on dialysis right away, but it’s possible to live well with kidney disease for many years,” says Sukhi. Most people will require diet and lifestyle modifications, or medications, to manage the effects of their poorly functioning kidneys and prevent conditions like high potassium or low hemoglobin levels. For most people, kidney damage can’t be reversed, but it can be slowed and the effects can be managed.

Most often, kidney disease occurs when a separate condition or disease impairs their function, so treating the underlying cause is also very important, says Hesketh. “If someone has kidney disease due to diabetes, high blood pressure or vascular disease, those patients first treat those issues,” she says. If someone has an underlying infection (like hepatitis B) or an inflammatory condition or autoimmune disease (such as lupus) that is causing their kidney failure, they can take medications to manage that issue, relieving the burden on the kidneys. “Ideally, we do these things to keep the kidney function from getting worse, but inevitably chronic kidney disease will progress over time and eventually some patients may require dialysis or a kidney transplant,” says Hesketh.

For many, a transplant is the only way to get off dialysis—a therapy that can be quite life-altering, says Hesketh. Dialysis treatment can be emotionally draining, a financial burden and an enormous time commitment. Plus, there are the physical side effects, which range from low blood pressure (for patients on hemodialysis) to high blood sugar (for people on peritoneal dialysis). “Patients on dialysis need a tremendous amount of support,” Hesketh says.

Know your risk factors

The risk factors for kidney disease include some you can control, like smoking, and others you can’t. “The most common causes of kidney disease are diabetes and hypertension,” says Sukhi. Diseases of the blood vessels put a lot of pressure on kidney function, which causes damage over time. There are also structural kidney diseases that arise from things like urinary obstructions or hereditary conditions. People of Asian, South Asian, Hispanic and Caribbean descent are at higher risk for kidney disease in general for a variety of reasons. And Indigenous people in Canada are more than three times as likely to have their kidneys fail. People who take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs)—like Celebrex to treat arthritis, for example—may also be at higher risk for this disease.

Supporting the health of your kidneys

For the most part, maintaining well-functioning kidneys comes down to a healthy lifestyle and managing other medical conditions. “If you know there’s a family history of [type 2] diabetes or hypertension that affects the kidneys, know that you should do everything you can to avoid it,” says Sukhi. “You don’t want to wait until you are told you have low kidney function, because at that point they are already damaged.” And, in most cases, that kidney damage can’t be reversed.

Next: “I’m Waiting for a Kidney Transplant. Again.”

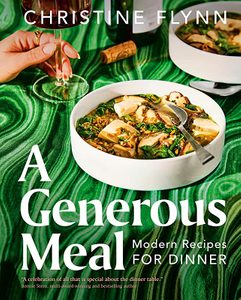

I made a version of these by accident when I was trying to bake cookies with my daughters on a lazy Sunday. We were all out of brown sugar, so I added some molasses along with the white sugar. I was a bit heavy-handed, and I worried that the cookies would taste too much like a molasses cookie. Instead, they turned out to be the most perfect, chewy, dare I say, satisfying chocolate chunk cookie I’ve ever made.

Dark Chocolate and Molasses Cookies

Makes 12 large cookies

Ingredients

- ½ cup (125 mL) unsalted butter, room temperature

- ¾ cup (175 mL) granulated sugar

- 2 tablespoons (30 mL) fancy molasses

- 1 large egg

- 2 teaspoons (10 mL) pure vanilla extract

- ½ teaspoon (2 mL) espresso powder

- 1¼ cups + 1 tablespoon (315 mL)

- all-purpose flour

- 2 teaspoons (10 mL) cornstarch

- 1 teaspoon (5 mL) baking powder

- 1 teaspoon (5 mL) baking soda

- ½ teaspoon (2 mL) kosher salt

- 1 cup (250 mL) dark chocolate chunks

Directions

In a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter, sugar, and molasses on high speed until fluffy. Add the egg and vanilla. Add the espresso powder.

Mix until well combined.

In a medium bowl, sift the flour, cornstarch, baking powder, baking soda, and salt. Add the dry ingredients to the butter and sugar mixture. On low speed, mix until just combined. Add the chocolate chunks. Stir to combine. Cover the dough and chill in the fridge for at least 2 hours, or overnight.

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C). Line a baking sheet with parchment paper. Remove the dough from the fridge and let it sit at room temperature for 10 minutes.

Roll the chilled dough into 1½- to 2-inch (4 to 5 cm) balls. Arrange them on the prepared baking sheet. Press each dough ball slightly to flatten. Bake for 8 to 10 minutes.

Remove from the oven and slam the baking sheet once, sharply, against a hard (non-chippable) surface to help the cookies settle. Let cool on the baking sheet for 5 minutes. Transfer the cookies to a wire rack to cool completely.

Store the cookies in an airtight container at room temperature for up to 5 days.

Excerpted from A Generous Meal by Christine Flynn. Copyright © 2023 Christine Flynn. Photographs by Suech and Beck. Published by Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: A Recipe for Brothy Farro with Mushrooms and Tofu to Add to Your Dinner Rotation

In the summer of 2004, I was an intern at the Los Angeles Times. I kept hearing about Chris Snow, one of the star interns from years past. Later, I got an internship at the Boston Globe, where he was a reporter covering the Boston Red Sox. This guy is everywhere I go, I thought. When we finally met, he had pretty eyes and a nice smile. That was it. We got engaged the next summer.

In 2011, I was pregnant with our first baby when Chris was offered a dream job as director of video and statistical analysis for the Calgary Flames. We moved to Canada when our son was five weeks old. Our daughter was born three years later.

When we were dating, Chris told me that ALS ran in his family. It’s a devastating neuromuscular disease with a life expectancy of six to 12 months. ALS mostly occurs sporadically, but about 10 percent of cases are genetic. That’s how it is in Chris’s family. In 2003, his uncle died from the disease; another uncle died a decade later. In 2016, Chris’s 28-year-old cousin died. Two years later, ALS took Chris’s dad from us.

Chris had a chance of having the genetic mutation that causes ALS, but we didn’t know if he did—it was always a question. Then, in 2019, when he was 37 and I was 35, he started to have numbness in two fingers on his right hand. Anyone else would have thought it was a pinched nerve, but we were on high alert.

We immediately started looking for a diagnosis. It takes, on average, more than a year to be diagnosed with ALS, which means most patients are unable to join what few clinical trials there are while they still have time. If you’ve had symptoms for any length of time, you become ineligible for many drug trials. These trials are designed for very select patients who are most likely to benefit—so it’s usually people who are in the earliest stages of the disease.

We moved quickly. That June, we flew to the University of Miami to see a specialist in familial ALS who had cared for Chris’s dad. It was the first time we’d both been away from our kids overnight. They were four and seven, and it was Father’s Day. We couldn’t tell them that we were going to find out if Daddy had the same illness that Grandpa Bob died from. We said it was a work trip and I was tagging along.

Chris went through testing and then we sat in a little room with the doctor. He told us that Chris was in the early stages of ALS. In the next breath, he told us that the first step was for us to join a clinical trial—Chris qualified for the first-ever stage three ASL trial for gene therapy.

I don’t know if the doctor ever said the word “hope,” but that’s what I deduced: We could have hope. Right away, I knew our story would be different because very few families with this disease ever get hope. Most people are told to go home, do what you love, get your affairs in order and die.

We were so scared, but we leaned hard into hope. Chris had a one-in-three chance of being on the placebo. A one-in-three chance is devastating when your life expectancy is less than a year. I look back on that time and wonder how we kept putting one foot in front of the other, not knowing. But we were pretty sure he was not on placebo because we saw an immediate slowing of the progression of his disease.

That October, Chris stepped onto the ice with our son, Cohen, for hockey practice for the first time since the changes in his hand. Chris hadn’t been able to get his hockey glove to stay on because his right hand just flopped around. But the equipment manager for the Flames molded Chris’s glove into a fist. Chris also wore a hand brace and I used a hair tie to hold the glove onto the brace. But then when he shot the puck, it lifted into the air and pinged off the crossbar! I knew then he wasn’t on the placebo.

In the fall of 2019, Chris was promoted to assistant general manager of the Flames, and we went public with his diagnosis in December. I started writing about it on my blog, Kelsie Snow Writes. As I kept writing, people sent me messages about their grief and their own sad stories.

At first, I found myself running hard from any sad story. I didn’t want to hear it. I wanted to stay locked in this world where we had the special sauce and everything was going to go well for us, and we were going to be the exception. But that’s not how this works. It took time to accept that.

This is a lonely place to be—this place of your husband never getting better. One of the hardest things about an illness (or a loss or tragedy) is the notion that nobody understands. Everyone else’s lives are still going on. And you’re here, socked into your own misery and nobody sees you. I realized I wanted to be around people who understood how I felt, the people who made me feel like I could keep moving.

To feel supported, I needed the stories of others. I needed to hear how people survive loss. So I started a podcast, Sorry, I’m Sad. I talk to people about their sad stories, and I feel lighter for having difficult conversations. I don’t ever feel like I’m weighed down by somebody else’s story.

In the beginning, I thought maybe the medicine was enough; that Chris’s ALS was not going to progress. But it’s been really hard lately. About nine months after we started on the trial, I went to take a picture of him and our daughter, Willa, and I noticed that his smile had a little droop. That started an aggressive cascade of losses, including control of his facial muscles. He lost his ability to smile, raise his eyebrows, make expressions. Chris said it was like being diagnosed all over again.

Speaking is getting more difficult. He can’t project or make hard consonant sounds. He lost his ability to swallow, and we worry about him choking, so now he uses a feeding tube.

We’ve dealt with a lot of scary things, like aspiration pneumonia and emergency rooms and the ICU. We’ve been sad and tired and angry. We have all these problems that we have to troubleshoot, and we have to grieve whatever the latest loss was.

I’m settling into this realization that, yes, it is a huge miracle that Chris is still alive. But he’s never going to get better. You wonder if people still want to hear about it.

I focus on the small moments. The other day, I watched my daughter stick her hand out the car window, moving it through the air like a wave. And I thought, That’s what I’m here for. These moments. What we have right now is beautiful.

Next: Caring For My Dying Mom Showed Me That Caregivers Need More Support, Too

According to Dr. Jeffrey Campbell, a urologist at St. Joseph’s Health Care London (St. Joseph’s) in Ontario, Canada, erectile dysfunction can be a sign of cardiovascular disease or an impending heart attack within two to three years from when a patient first experiences an issue with their erection.

How the body works

Getting and maintaining an erection is controlled by the vascular system, also called the circulatory system, made up of the vessels that carry blood throughout the body. “The blood vessels in the penis are smaller than the blood vessels in the heart,” says Dr. Campbell. “If those smaller vessels are affected and causing erectile dysfunction, it can be an early indicator of vascular disease.”

What causes erectile dysfunction?

A number of conditions can trigger erectile dysfunction such as diabetes, obesity, poor blood supply, low testosterone and problems with the physical structures that close off the veins in the penis. “It’s rare for erectile dysfunction to be caused by one singular issue,” adds Dr. Campbell. “One of the most underappreciated causes of erectile dysfunction is psychological. A lot of men have a belief of how things should perform and they get performance anxiety or worries about their sexual function.” Medication side-effects can also cause erectile issues adding to the complexity of men seeking treatment for mood disorders such as depression.

Talking about it is the first step

Dr. Campbell encourages men to seek out medical advice early for erectile dysfunction to get to the root of the problem. However, opening up about difficulties in the bedroom can be uncomfortable. “A lot of men don’t want to believe anything is wrong and as soon as they discuss it they feel like they’re a failure. I remind my patients, this is a normal, natural physiological process and there is no need to be embarrassed.”

Treatment for erectile dysfunction

There are treatment options available ranging from counselling to surgery. Dr. Campbell discussed the various treatments for erectile dysfunction with award winning Canadian journalist Ian Gillespie on St. Joseph’s DocTalks Podcast. “Each individual treatment plan is unique and it’s important for patients to know there is help.”

Listeners can tune into the DocTalks Podcast for free on their computer or smart device through established platforms like Apple Podcast and Spotify. Each episode features a trending health care conversation, including insights on leading-edge treatments and research from an expert physician. Listen and subscribe to DocTalks Podcast wherever you get your podcasts or visit sjhc.london.on.ca/podcast.

Renowned for compassionate care, St. Joseph’s Health Care London is one of the best academic health care organizations in Canada dedicated to helping people live to their fullest by minimizing the effects of injury, disease and disability through excellence in care, teaching and research.

I’ve always caught up with friends over glasses of wine or pints of beer. But lately, I’ve been spilling the tea over, well, actual cups of tea instead. Turns out, it’s just as satisfying and much better for me, too.

That doesn’t mean I’ve given up alcohol completely. I decided this would be the year that I drink less. So, instead of starting the year off with Dry January, in which I wouldn’t allow myself to have a single glass of alcohol, I’m doing a Damp Year, where I consciously reduce my alcohol consumption all year long.

I have many reasons for cutting back. First and foremost, the updated guidelines from the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) recommend women have no more than two drinks a week to avoid an increased risk of seven types of cancer, cardiovascular diseases and liver disease. It’s a pretty drastic reduction from the 2011 guidelines, which recommended women have no more than two drinks a day to reduce long-term health risks, so I’m feeling a push to modify my habits.

(Related: A Science-Backed, Data-Forward, Awfully Sobering Guide for Women Who Drink Alcohol)

While alcohol is harmful to everybody, it can have worse impacts on some people. I’ve always considered myself a “lightweight”—meaning, I feel drunker, faster than most people. And this is, in fact, a thing. “People respond differently to alcohol,” says Scott Hadland, a physician at Mass General Brigham in Massachusetts. For instance, “people who have a lower weight may have more difficulty tolerating alcohol, as do people who don’t drink much alcohol,” he says, which may lead to more injuries and health issues.

Plus, I’m Chinese and suffer from occasional bouts of “Asian flush.” If I drink too quickly, or too much, my face (and, sometimes my whole body) turns red, accompanied by a quickened heart rate and a headache. According to a 2015 study published in Cancer Epidemiology, the “alcohol flushing response” means I’m at greater risk of esophageal cancer. Turning red is, quite literally, my body’s way of telling me to stop drinking.

So, why am I not cutting out alcohol completely? Banning things I love has never worked for me—I will unapologetically succumb to any cookie or French fry because life’s about enjoying things you love. Alcohol is something I like consuming, so I don’t want to give it up. According to dietitian Abby Langer, I don’t necessarily need to. In her book Good Food, Bad Diet, (which she talked to Best Health about) she says she advises her clients to indulge in food cravings responsibly to reduce feelings of guilt or shame. Also, when you never let yourself enjoy the things you love, you get “miserable AF,” she says. Since I have a healthy relationship with alcohol, I’m not going to let myself feel guilty about enjoying a glass of wine, pint of beer or cocktail once in a while. I don’t have a hard limit of what I can consume each week, but on average it’s one or two drinks—about a third of what I used to consume.

I can’t say it’s easy—I’ve had to change my habits, including how I drink at home and how I make healthy choices when I’m out with friends. And I’ve found that moderate drinking, and being mindful of how much alcohol I’m consuming, takes a little hacking and planning. So, here are the tricks that have helped me reduce my alcohol intake.

At home:

Opt for canned wine: When on my own, opening a bottle of wine compels me to finish it on subsequent evenings, which means I’m clocking four servings of alcohol well before the week is through. A can of wine allows me to have one to two glasses, with zero regrets of wasting any—or drinking more than I wanted.

Stock up on non-alcoholic options: How are you supposed to encourage yourself to opt for an alcohol-free drink when you have no enticing options on hand? Explore the flavoured sparkling water aisle, invest in some alcohol-free spirits and make your choices more appealing.

Find a new way to unwind: If you usually celebrate the end of your workday with a glass of wine, adopt a new habit, like enjoying a bath, a fitness class or a gummy. The trick to actually follow through? “Remind yourself of the reasons you’re moderating your approach to drinking,” says Terri-Lynn MacKay, a registered psychologist and clinical director of Alavida, a virtual care app for substance abuse. “Put stickies on your fridge, record a voice prompt on your phone or write in a journal,” she says.

At a bar or restaurant:

Choose a spritzer or low-alcohol cocktail: Less-boozy options are appearing more often on cocktail menus. If they’re not listed, just ask the bartender, or try a wine spritzer (great for weddings or events with limited choice) or a liqueur and soda (like a spritz but without the sparkling wine). Campari is my go-to liqueur, but vermouth, St. Germain (elderflower liqueur) and Aperol are also great options. If a 142 ml (5 oz) wine spritzer is made with half wine, half soda, you’re only consuming half of a serving of alcohol, according to CCSA guidelines. The same goes for liqueurs—the CCSA says one serving of spirits (whisky, vodka, gin) is 43 ml (1.5 oz) of a 40 percent alcohol spirit. But since liqueurs clock in at 11 to 25 percent alcohol, your serving size of alcohol goes down by a similar proportion.

Order a half-pint of beer or a low-ABV (alcohol by volume) beer: These aren’t always advertised, but most bars will be happy to pour you a smaller serving. And most menus have their beer’s ABV percentage listed. If not, ask your bartender, or go for a radler or session ale, which are lower in alcohol.

Eat before you drink: Having some food, like a fatty, carby snack, before drinking helps you better tolerate alcohol so you can make better decisions, like whether or not you’ll have another drink. “This easy strategy slows down the speed at which alcohol hits your system,” says MacKay. Wait until after the appetizer arrives to order your first drink, or have a snack at home before you leave if you anticipate drinking right away. “Nuts, peanut butter or cheese are handy to put in the stomach before eating,” explains MacKay. “Chips are good too because they have a higher fat content.”

Tips in general:

Experiment with different low or no-ABV brands: If you’ve tried one non-alcoholic beer and weren’t a fan, don’t write off them all—there are many options on store shelves these days, and you’re sure to find one you like. If you need a place to start, try Partake and Libra for beer, Frico and Joiy for canned wines, and Sobrii and Lyre’s for non-alc spirits.

Set weekly consumption goals: “Make choices about when and where you will drink in advance,” says MacKay. If I plan to drink for a friend’s birthday on the weekend, I’ll opt not to drink during the week.

Change your habits: “Try to better understand the function alcohol serves when you want to drink,” says MacKay. “Are you using alcohol to reduce stress, lubricate social situations, enhance your libido, manage negative emotions?” If so, you may want to find other ways to meet those needs. For me, I’ve found catch-ups with friends to be equally enjoyable without alcohol.

How’s my Damp Year going? Well, I’m sleeping better, I feel great having fewer hangovers to contend with, and I’m saving a bit of money when I go out. I still drink on occasion (a friend’s birthday, for example), but I can better appreciate the times that I do drink. Plus, I’m getting more comfortable with socializing without alcohol, too.

Next: Not Drinking Alcohol? No Problem. Add These Drinks to Your Bar Cart