The microbes that naturally flourish in our nether regions are team players: They support a delicate equilibrium and help to keep our reproductive organs healthy. Though scientists have known for over a century that the vagina’s microbiology is complex, they are just starting to crack the microscopic code of what keeps it balanced and what throws it out of whack. Just like with gut bacteria—which have been linked to a plethora of issues including weight gain and mood disorders—the vagina’s particular microbial mix is now thought to play a role in mediating the risk of certain cancers, protecting against STIs and vaginal infections and, potentially, bringing pregnancies to term.

(Related: Are Your Bath Products Bad for Your Vag?)

Like plenty of things bits-related, the vaginal microbiome gets swinging during puberty. (The microbes are thought to proliferate as estrogen shoots up, though more research is needed to confirm this link.) That’s when lactobacilli, a type of bacteria that produces lactic acid, start getting cozy in the female sex organs. The Lactobacillus crispatus variety (which experts call L. crisp, aka the Queen Bee of vag bacteria) helps create an ideal vaginal pH below 4.5.

(Researchers think these lactobacilli may originate in the gut and find their way to the vagina because of its proximity to the anus—a totally normal biological phenomenon, and nothing to worry about.) An acidic environment is necessary for vaginas to keep them better protected from invading bacteria and fungi. In many women, L. crisp will make up 95 percent of the vaginal microbiome. Unlike in the gut, which is home to a thick layer of mucus, bacteria in the vaginal canal live directly on its internal epithelial tissue.

Hints about the vagina’s microbiological complexity first showed up under microscopes in the early 1900s, when scientists were baffled by the rod-shaped lactobacilli and deposits of glycogen (a form of glucose) they were seeing in these tissues. Glycogen plays a role in the body’s energy storage and is usually found in the liver, so scientists were surprised to find it in the vagina, explains Laura Sycuro, an assistant professor at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine who runs a research group that investigates the vaginal microbiome. More than a century later, researchers are still working to prove their hypothesis (and, due to chronic underfunding, it continues to be a hypothesis) that glycogen feeds the lactobacilli. What researchers like Sycuro are starting to understand is that this living environment is constantly in flux, as it’s altered by things like menstrual flow, pregnancy, menopause or the exchange of bodily fluids.

Why the microbiome matters

Thanks to millennia of medical literature dominated by male voices, there’s a fundamental and pernicious misunderstanding of how female bodies work. For example, drawing on Ancient Greek ideas, physician and chemist Edward Jorden claimed in a 1603 text that uteruses were prone to…wandering. Then there was the 19th-century belief that women shouldn’t board trains because travelling at more than 50 miles per hour could make our uteruses shoot out of our bodies (yes, really). We may now have at least basic female anatomy figured out, but women’s health continues to be underexamined, and the vaginal microbiome in particular remains—unnecessarily—an enigma. Researchers still have to fight for funding and are often faced with surprising ignorance when it comes to female biology. “Reviewers fundamentally did not believe me that bacterial vaginosis, or BV, is caused by bacteria, and I’m like, okay, so this is 30 years of clinical research,” says Sycuro. (The review panel insisted that fungi are also a major player in vaginosis, but Sycuro says that’s complete nonsense.)

Every year, bacterial vaginosis—an infection that’s intimately linked to the vaginal microbiome—affects about 30 percent of vagina-havers worldwide and costs health-care systems billions of dollars in doctor visits and treatment. BV is more common than yeast infections—it’s responsible for 40 to 50 percent of diagnosed vaginitis infections—and it’s tied to both preterm births and HIV infection. (Studies show that BV increases the risk of HIV infection in women by 60 percent.) BV—which has symptoms such as thin discharge and the occasional fishy smell—is often trivialized by the scientific community, says Sycuro, because it’s not fatal. But it’s still a hugely disruptive hassle that causes discomfort and, unfortunately, the unwarranted shame that many women feel or associate with their genitalia.

BV isn’t the only culprit causing issues under our undies, of course. Yeast infections are to blame for another 20 to 25 percent of vaginitis cases—but they aren’t bacterial, they’re fungal. These infections are caused by yeast overgrowth, and are accompanied by thicker discharge and the occasional itching or burning sensation.

And as for those dreaded burn-when-you-pee urinary tract infections, rather than an internal imbalance, they can be caused by a pathogen from the GI tract—like E. coli—getting into the urethra and bladder.

Unlike yeast infections, for which you can get over-the-counter anti-fungal creams, treatments for BV are limited—a prescription for antibiotics is the only option, and it comes with its own slew of potential issues. “Once [patients] are in that loop, every time they take antibiotics, they have a 50 percent chance of needing the antibiotics again within six to 12 months,” says Sycuro. Antibiotic over-prescription can also increase a person’s anti-microbial resistance and alter their gut microbiome diversity. Translation? These medications clear out the bad guys, but they don’t necessarily restore perfect balance, and sometimes the bad guys return. Patients end up back at square one, taking more pills that further disrupt the vaginal microbiome.

The cancer connection

Research is underway to examine the vaginal microbiome’s role in protecting against sexually transmitted infections like chlamydia, gonorrhea and HIV: Sycuro’s lab is currently studying whether chlamydia bacteria can attach better to a receptor when certain other bacteria are present. This is especially important because some research findings suggest that chlamydia is associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer.

Compared to, say, prostate cancer, says Sycuro, female-specific diseases such as ovarian, uterine and cervical cancers are understudied, and harder to detect at early stages. While prostate cancer can be detected early through blood tests, women don’t have that luxury when it comes to ovarian and uterine cancer: An estimated 1,950 of the 3,000 Canadian women diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022 were predicted to die, according to the Canadian Cancer Society, mostly due to it being caught too late. (Pap tests only help detect cervical cancer.)

What’s next on the horizon

When it comes to long-term solutions to chronic BV, Sycuro says there is a glimmer of hope. Inspired by fecal transplants used to improve digestive health, scientists are experimenting with transplanting fluid from healthy vaginas into ones with chronic BV. This procedure is still in the clinical trial phase, with research underway in places like the Kwon Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Sycuro estimates it might take another decade for the process to become widely accessible. In the meantime, we need to dodge the savvy marketing behind iffy products that try to fill that medical void and claim to support “vaginal wellness.”

Next: What’s With All the Vaginal Creams, Wipes and Gummies?

Kourtney Kardashian recently stepped into this spotlight with a cat-themed marketing campaign designed to convince us that we need to treat our vaginas like a candy store. (Her—cringe—Lemme Purr gummies, which are ingested orally, are supposed to support the health of the vagina and make it taste sweeter.)

“Miracle cures for vaginal imbalances can essentially go unchecked and are still mostly snake oil,” Sycuro says. “We don’t have regulatory bodies that mandate [they] have evidence.”

“The vast majority of creams, sprays and douches are great marketing, and terrible for women’s health, because they disrupt the normal balance,” adds Money.

Our experts’ blanket recommendations: Stop watching TikTok videos, leave your crotch alone to self-clean (like an oven!) and don’t let Gwyneth Paltrow or reality TV stars convince you to put anything up there, jade egg or otherwise.

Don’t bother with

Probiotic supplements ingested to “increase beneficial bacteria” in the vagina

“The clinical trials haven’t been a smashing success yet,” says Sycuro—meaning anything selling itself as a vaginal microbiome health miracle pill, or claiming to make our private parts “fresher,” is premature.

Do consider

Boric acid suppository to balance vaginal acidity

This is one treatment in which Money sees some value, though with a few caveats. “Boric acid actually can be quite good as a suppressant of yeast infections and recurrent bacterial vaginosis,” she says. But, she emphasizes, you need to seek a professional diagnosis rather than just a Google search result—and get a prescription rather than going DIY.

Definitely skip

Vaginal steaming with herb-infused water

At this point, you might have a hunch that this is a no-no. Though people use vaginal steaming to allegedly tighten and freshen up the area, overheating your genitals can help bacteria thrive, leading to infections. “The cells of the skin on your face [are] dead and hard, and you want to slough them off. But the ones on the surface of the vagina are softer and partially alive […] and vaginal steaming can definitely change how protective and healthy that tissue is,” says Sycuro.

Please don’t try

Yogurt

Yes, patients do ask Money about smearing yogurt directly into the vagina as a natural probiotic. Her response? “It’s a great food.” Eat it for breakfast and leave it at that.

Next: A Field Guide to Your Vaginal Microbiome

The self-swab test kit Evvy (currently only available in the U.S., at evvy.com) is designed to help women “know what’s up down there,” providing a breakdown of the vagina’s bacteria and fungi composition. Evvy highlights the gap in women’s health care with taglines like “the female body shouldn’t be a medical mystery,” and tells users they’ll be able to “catch imbalances before they become infections.”

How does it work? Users swab themselves and send in the sample for a full analysis, which they receive through an app, along with a game plan of recommendations. Customers can also elect to receive a follow-up call with a “certified health coach.”

(Related: What’s With All the Vaginal Creams, Wipes and Gummies?)

Like many femtech innovations, the product definitely taps into an unmet need. But at $129 USD per kit, plus an optional subscription model for follow-up tests and care, the company also makes a pretty penny trying to fill that gap. This allows wealthier women to believe they have a better knowledge of their microbial makeup, but provides few ways to put that information to good use. Plus, there’s the subtle suggestion that this is yet another female body part we should feel insecure about. (Wait, should I be more worried about my vagina?)

Deborah Money questions the kit’s usefulness. “If you actually have a problem, then you need a diagnosis and a treatment,” she says. And if women who complete the kit are ultimately told to talk to their doctors anyway, she worries users are wasting money and time, instead of seeing an OB/GYN in the first place.

Laura Sycuro has a theory: “What’s at the heart of [this] is women not feeling safe, listened to or validated by their care providers,” she says. The fact that we don’t feel seen by doctors opens the door for our bodies to be turned into a profit opportunity. Private companies have created countless overpriced “for her” personal products, but more dangerous than pink-washed soaps and razors is the fact that we remain understudied in many ways, and that includes a lack of understanding how certain diseases can manifest differently in women.

Next: A Field Guide to Your Vaginal Microbiome

Fried rice is for Thai people what pizza is for North Americans: a standard base that you can then top with just about anything, making it the ideal dish for using up leftover bits of meat and veg. But unlike pizza, fried rice is easy and fast to make! A basic fried rice recipe such as this one is a good tool to have in your back pocket, and it will work with any protein, even strongly flavored ones. We don’t usually add veggies to our basic fried rice, but to serve it Thai style, you’ve got to have fresh cucumber slices, a lime wedge, and some prik nam pla on the side!

Leftover Anything Fried Rice

Kao Pad Kong Leua | ข้าวผัดของเหลือ

Serves 2

Cook time: 5 minutes

Ingredients

- 2 tablespoons (30 ml) neutral oil

- 6 cloves (30 g) garlic, chopped

- 2 large eggs

- 2½ cups (375 g) cooked jasmine rice (see sidebar on p. 203)

- 1 tablespoon (15 ml) soy sauce, preferably Thai (use a bit less if your leftovers are salty)

- 2 teaspoons (10 ml) fish sauce

- 1 teaspoon (5 ml) granulated sugar

- ¼ teaspoon (1 ml) ground white pepper

- 4.6 ounces (130 g) leftover protein, shredded or chopped

- 1 green onion and/or 4 to 6 sprigs cilantro, chopped

For serving

- English cucumber slices Lime wedges

- Prik nam pla (fish sauce & chilies condiment)

Directions

Place a wok on medium heat and add the oil and garlic. Once the garlic bubbles, stir for 1 to 2 minutes, until the smallest pieces start to turn golden.

Add the eggs, scramble slightly, then let them set about halfway before stirring to break up the pieces.

Turn the heat up to high, then add the rice, soy sauce, fish sauce, sugar, and pepper; toss to distribute the sauce evenly.

Add the protein and toss to mix, then let the rice sit without stirring for 10 to 15 seconds so that it can toast and develop some browning and flavor. Toss to mix and repeat this toasting step a few more times. Turn off the heat, then taste and adjust the seasoning.

Toss in the green onions and/or cilantro to taste, then plate and garnish with more fresh herbs, if desired. Serve with cucumber slices, lime wedges, and some prik nam pla, if you wish.

Tip 1: Use Those Drippings! I first used this recipe with leftover supermarket rotisserie chicken, and if you’ve ever had rotisserie chicken, you’ll know that at the bottom of the container lie delicious chicken juices. And the same might be true with whatever leftover meats you have—drippings or juices sitting at the bottom of the plate. This is liquid gold that should absolutely go into your fried rice. However, be mindful of how salty the liquid is, and cut down on the soy sauce or fish sauce accordingly. Also, don’t add more than 2 to 3 tablespoons (30 to 45 ml) liquid for this recipe, so as to not make it too wet.

Tip 2: Old, cold rice for fried rice is great, but you don’t need it. If cooking fresh rice, wash the rice at least three times, until the water runs clear, then use a little bit less water to cook it than you normally would (I do a one-to-one ratio for jasmine rice). If you have time, spread the rice out onto a plate to let it dry out before cooking. I also recommend weighing the cooked rice for accuracy, but if measuring by cup, press the rice in just enough so there aren’t any big gaps, but do not pack it tightly. Finally, if you don’t have a large wok, I recommend cooking in two batches to maximize rice toasting, though you can cook all the protein at once.

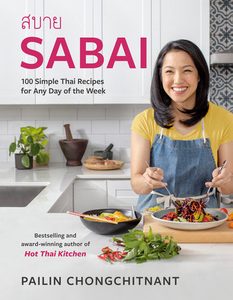

Excerpted from Sabai by Pailin Chongchitnant. Copyright © 2023 Pailin Chongchitnant. Photographs by Janis Nicolay. Published by Appetite by Random House®, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next: 3 Cozy, Delicious Thai Recipes to Try at Home

In June 2022, our national supply of blood was at its lowest in a decade. That’s especially worrying when the inventory has such a short shelf life: six weeks for red blood cells, and just five to seven days for platelets, the tiny cell fragments that help with clotting.

Giving blood can be challenging for all sorts of reasons, from the needle itself to the hour-long time commitment to the fact that Canadian Blood Services (CBS) restricts who can donate. Residual fears over the possibility of HIV transmission through transfusions meant that, until 2016, people who were born or had lived in certain African countries, including Nigeria and Chad, were prevented from donating blood, while men who have sex with men had to contend with revolving restrictions, from an outright ban that lasted until 2013 to various abstinence requirements (five years, one year, three months) before last September. As HIV-detection tests improved, and the tests became cheaper and more readily available, these bans became difficult to defend, and CBS has finally scrapped asking questions about gender or sexual orientation. Now, all potential donors are asked to wait at least three months after having anal sex with a new partner (or multiple) before they donate.

“Evidence has evolved, test technology has advanced and, at the same time, awareness of the importance of an inclusive blood system has increased,” says Jennie Haw, a social scientist at the CBS whose research includes non-donor, donor and donation policy and the social and political contexts of donation.

Here, Haw explains why the start of the pandemic was such a banner time for giving blood, why it matters to have donors from a diverse range of ethnic and genealogic communities and why our supply problem probably won’t be fixed by handing donors a VR headset.

Let’s start with a big one: Why do we need people to donate blood?

So that we have blood and blood products for patients who need it. That can be because of accidents or in trauma care; it can be for many kinds of surgery. There are also conditions for which regular blood transfusion or red-cell exchange is necessary for treatment. Canada has said we’re going to have a voluntary, unpaid system. And so to meet the needs of patients, we need people to donate blood.

What actually brings people through the door to donate?

When you ask donors why they donate blood, the vast majority say it’s because they want to help someone else. There is a psychological phenomenon called a warm-glow effect, where people feel good because they’ve done something good. Another motivation has to do with social recognition: It’s something that’s valued in one’s community; it’s considered to have social capital. And then there’s a kind of reciprocity—someone might know someone who needed blood, so they want to contribute, too.

At the very start of the pandemic, there was a surge in blood donations in Canada. Do crises tend to galvanize people?

Absolutely. Across most national emergencies, you’ll see an upswing in people wanting to help. In the States, after 9/11, there was a massive outpouring of people donating blood, and I know when there are bushfires in Australia, people turn out as well. A colleague and I did a small study in the early days of the pandemic to understand the experiences of people coming out to donate. We found that, for a lot of donors, this was an important opportunity for them to be able to actually interact safely with people who weren’t in their household. Maintaining community was important to them, and this was a way to do that.

Why don’t people donate? What makes it a challenge—or makes it unappealing—for them?

Right now, as restrictions have loosened, I think people have other activities they could be involved in. But more broadly, it’s a really interesting puzzle, and an area where I think we need more research. It’s definitely easier to ask someone “why do you do this?” than it is to understand a phenomenon where something isn’t being done. One way to study why people don’t donate is to look at barriers to donation. It could be a lack of knowledge of the process of blood donation—so not quite understanding how to register, what happens when blood is drawn, what happens to the blood afterward. There can be barriers at a personal level, like a fear of needles. And then there can be systemic barriers, like a lack of trust with the blood operator and a lack of trust with the health-care system, which extends to a lack of trust in the blood system.

There have also been outright bans on certain donors—for example, men who have sex with men, or, up until 2016, anyone born in specific African countries. What impact did those restrictions have on donor engagement?

I haven’t studied that restriction specifically, but sometimes when eligibility criteria change, people don’t necessarily know and it can take time for people affected to be aware of that change.

But when CBS changes a policy about donation, shouldn’t it be responsible for outreach to the people affected?

This is kind of outside the scope of the work I do. But I think any institution or organization asking for people to come and participate voluntarily would want to make sure that the general public knows when there are changes to eligibility criteria.

Why is it important to have donors from different backgrounds?

For a condition like sickle cell disease, one of the treatments is regular blood transfusion or red-cell exchange. And for people who have more rare blood types or are frequently transfused, the closer the blood type matches with the donor, the better the health outcomes. Because blood antigens are inherited, you’re more likely to find a close blood-type match with someone who shares an ethnic ancestry. This doesn’t mean that you can only donate to someone of the same ethnic ancestry—but the more ethnically diverse the donor base, the better positioned Canadian Blood Services is to find close matches for the very diverse population that they serve.

How can we make donor screening as inclusive as possible?

It takes a multidisciplinary approach and a team of people to move donor screening toward inclusivity in a safe way. It requires clinicians and epidemiologists to look at the various risk factors and how to ensure the safety of the blood supply. Plus social scientists to examine the questions asked to be sure they are understandable and accessible. For example, in September, a change was made to ask about sexual behaviour regardless of gender or sexual orientation, and to be more inclusive of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. But it’s a big challenge. And there isn’t necessarily a one-size-fits-all answer.

What about just paying people for their blood?

I know there’s research being done on incentives to donation, and paying donors is one of those options. I don’t know what the impact of paying donors would be.

Speaking of incentives: Las Vegas just introduced a virtual-reality experience for donors. Maybe Canadian Blood Services wants to look into that?

I didn’t know about Las Vegas incorporating VR, but if it was going to happen somewhere, it’d be Vegas. It’s important to keep in mind that the U.S. has a very different system than we have here in Canada. There has been some research looking into whether providing donors with added information—like their cholesterol levels or blood pressure—makes a difference in donor retention, and I think the jury was out on that. I can see how exciting, attractive measures might help a very pressing blood shortage in the moment. But understanding people’s motivations and the social norms underpinning a voluntary blood-donation system—it’s just a vast area of research. I don’t think it’s going to be solved through VR.

Next: How Mental Illness Shapes Our Identities

This story is part of Best Health’s Preservation series, which spotlights wellness businesses and practices rooted in culture, community and history.

When Ronke Edoho moved to Canada from Nigeria more than 15 years ago, one of the first things she noticed was the fruit for sale in grocery stores. The apples were perfect, round and glistening. Sometimes they had travelled a long distance to get to the aisles of her local market in Saskatchewan. This was strange for Edoho, whose food had previously come from her grandparents’ backyard in Kwara State, Nigeria. “I always felt like I was only one step removed from my food source,” she says. But in Canada, the fruit and vegetables looked nothing like the ones she pulled out of that backyard growing up. “Everything was packaged; nothing was misshapen.”

So, in 2013, when Edoho got married and bought a home in Saskatoon, she started a backyard garden to connect with her childhood experience. She began by planting tomatoes and peppers, then moved on to ingredients that are hard to source in Canada but are essential to her favourite traditional Nigerian meals. She planted amaranth greens, a leafy vegetable that’s a staple ingredient in Nigerian dishes like efo riro, a vegetable soup cooked with palm oil. Next, she experimented with jute leaves and waterleaf, which are used in soups like ewedu and edikang ikong and eaten with pounded starches like yam or cassava.

Edoho already had a successful food blog called 9jafoodie (9ja is colloquial shorthand for Nigeria) and an active online community where she shared Nigerian recipes. So when she started posting pictures of the haul on Instagram, she was inundated with requests. “People started asking, ‘Is this something I can do for myself? Can you teach me how to do it?” says Edoho. In 2021 she launched a new website, Jollof Code, as a shop, educational resource centre and visual diary of her own gardening journey. She shares videos of how she builds her garden beds and the progress of her fruits and vegetables. And, in addition to selling seeds for Nigerian vegetables like garden egg and waterleaf, she also offers courses on how to grow those vegetables anywhere in the world.

So far, despite the challenges of growing Nigerian vegetables in chilly Canada, Edoho has been successful with her garden—but not without hard work and experimentation.

“I wanted the authentic flavour of some of those things, [so] I went into the research. Like, what is the growing season?” she says. “And then I started experimenting with different kinds of soil and watering cycles.” When she noticed that ladybugs loved to snack on her amaranth greens, for example, Edoho grew more—the insects act as a form of pest control against other, more harmful critters in her garden. For vegetables like Nsukka pepper, which thrives in the tropical weather of southeastern Nigeria, Edoho works around Saskatoon’s frigid winter and short summer by starting the seeds indoors as early as February, then transferring them outdoors when the weather warms up.

On top of learning how to grow Nigerian food, people are looking for a way to connect with home, says Edoho. “It’s not just food for nourishment. It’s a connection to a time in the past.” She uses her platform to share knowledge about specific cultural foods—knowledge that is often lost with immigration. “I feel like my generation are like city folks two generations in. A lot of people didn’t have the opportunity to grow up on a farm or around chickens or goats. I love sharing that knowledge,” she says.

Edoho also relishes the chance to share what Nigerian food is like. As a student at the University of Saskatchewan, she started blogging to dispel misconceptions about Nigerian food that media organizations in North America and Europe often present as facts: “I still remember one [article] vividly that said African food is made with poorer qualities of goat, beef and fish.” The statement shocked and annoyed her, so she decided to do something about it. “There’s a lot the West does not know about us. And our food is just one [thing],” says Edoho. “I wanted to start something to educate people about the richness of the food. My dad tells me all the time: If something is not the way you like it, either you fix it, or you keep quiet.” Luckily for fans of Nigerian food and gardening, Edoho spoke out.

This story is part of Best Health’s Preservation series, which spotlights wellness businesses and practices rooted in culture, community and history. Read more from this series here:

Meet Sisters Sage, an Indigenous Wellness Brand Reclaiming Smudging

Bone Broth from This Canadian Ayurveda-Inspired Company May Help Soothe What Ails You

Have Super Dry Skin? This Canadian Skincare Company Is Here to Help

Get more great stories delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for the Best Health Must-Reads newsletter. Subscribe here.

The photo is horrifying. Taken from behind, the offending piece of evidence shows a spreading white circle at the crown of my head that glows as if it’s desperately signaling to its alien pals in a dimension far, far away. The evidence is clear: I’m not just going grey—I’m also going bald. And I’m not alone.

Hair loss in women can be sparked by a laundry list of factors including genetics, thyroid issues, stress, vitamin and mineral deficiency, the hormonal blitzkrieg of menopause and the general effects of aging on all our tissues, including the lusciousness of our locks. According to the Canadian Dermatology Association, about 40 percent of women will experience some form of hair loss by the time they hit 50. Since I pride myself on always being right on time, I started noticing naked spots as soon as I hit my late forties. I’ve never been a glorious Rapunzel, but this is just rude. Wearing a jaunty beret every day seems cute but impractical, so I started researching options. Treatments like platelet-rich plasma injections straight into my scalp to kick start hair growth or teeny, tiny hair transplants are expensive and painful; a topical like Rogaine is way too slow; and daily use of colour sprays have destroyed my pillowcases and couch. But then I discover a relatively simple way to fill in the sparse areas on my lid: a tattoo.

(Related: The Root Cause of Thinning Hair and Hair Loss for Women)

Scalp Micropigmentation, or SMP, is a cosmetic procedure that uses micropigmentation—a permanent makeup technique that’s already popular for filling in sparse eyebrows and tattooing on freckles— on the scalp. Artists use a pen-like tattoo machine to draw thousands of tiny dots that mimic hair follicles. If you’re bald, the results will look like you’ve just shaved your head, and if you still have hair but want to fill in some areas like I do, it camouflages the empty spots and makes the surrounding hair look thicker. It can also help hide scars and can be used on all skin tones, though if your scalp is prone to inflammatory skin conditions like psoriasis or eczema, you’ll have to clear that up before you can get SMP.

SMP is newish and permanent makeup isn’t regulated in Canada, making it simple for anyone to take a weekend course and say they’re certified, so it’s very much buyer beware when it comes to choosing a technician. SMP uses special inks and is super precise—if you go too deep with the needle the ink can spread into ugly blobs, but if you don’t go deep enough the colour will fade quickly—so it’s key to go to someone who has experience and whose facilities have passed municipal health code inspections (i.e. not some lady who does SMP as a side hustle in her basement!). A good place to look for a skilled practitioner is a medically supervised hair transplant clinic that also offers SMP. But I decide to go old school with a recommendation from Pretty in the City owner Veronica Tran, a permanent makeup artist who I’d gone to for my eyebrows, and end up at Scalp Amplified Studios in Oakville. “I’ve seen people tattooing people’s heads after watching videos on YouTube,” shudders owner Renata Pruszewski. “There are a lot of botch jobs coming out.” Pruszewski has been doing permanent makeup for 13 years, was one of the first SMP practitioners in Canada and has racked up several international SMP awards, so I feel safe in her hands. Which is good, because I’m going to be spending a lot of time with her scribbling on my head. People who want to cover near or total baldness need anywhere between two and four sessions at two to four hours each—it takes a lot of time to draw on all those wee dots—but because I still have a fair amount of hair, Pruszewski says I’ll only need two visits.

While the cost varies depending on how complicated the job is, prices start at around $700 per session. I’m game, but I’m worried about what will happen when my husband finally manages to pry the hair-dye bottle out of my cold, dead hands and I eventually let my hair go grey—an inevitability that even the vainest among us (hi! me!) must eventually face. Will I have a weird dark tattoo helmet under my snow-white locks? Pruszewski assures me that hair follicles are related to your skin tone, not the colour of your hair, so the SMP dots will still look natural even if I give up dyeing my hair. And, like all tattoos, SMP fades with time, especially if you’re not applying sunscreen—which most women don’t do to their scalp, even though there are specialty SPF sprays. While the results can technically last up to seven years, Pruszewski says many clients come in for touch-ups at the two-year mark.

I’m ready, and I feel bold. I was an emo Gen Xer, after all, which means I already have two actual tattoos. How bad can this be? The answer is: It’s not bad at all. While it’s definitely not pleasant, I find it pretty tolerable, like she’s drawing on my scalp with a very sharp pen for three hours. I’m able to chit chat and look at my phone, which, in my books, is about as good as it gets for a semi-permanent procedure involving a needle. There’s no bleeding, but my scalp is red and sore for a week, and so, so itchy. I’m not allowed to sweat excessively or wash my hair for three days (best. shower. ever), and while you’re technically fully healed after two weeks, Pruszewski says I shouldn’t dye my roots for a month.

But the results are instantaneous. When done well, SMP is both extremely subtle and quite noticeable in that it looks better, but you can’t tell what, exactly, has been done. And if the flood of intrigued messages I got from women after I posted some before-and-after pics on Instagram is any indication, it’s a procedure that’s about to get a lot more popular.

Next: Why You Should Tell Your Derm About Hair Loss

Pesto is a flavour-rich sauce (thanks to ingredients like fresh herbs and roasted nuts) that can elevate so many dishes. Here’s how to make pesto with peas and basil.

Pea and Basil Pesto

Makes: 1 cup prep time: 5 minutes cook time: 10 minutes

Ingredients

- ⅓ cup pine nuts, toasted

- 1 cup frozen peas, thawed

- 2 cloves of garlic, smashed

- ¼ cup olive oil

- 3 tbsp lemon juice

- 1½ cups fresh basil leaves, packed

- 1 tsp salt

Directions

1. Add pine nuts to a small skillet set over medium heat. Toast, tossing frequently, until lightly golden and fragrant, 3 to 5 minutes.

2. Combine pine nuts, peas and garlic in the bowl of a food processor or blender and pulse until peas and nuts are mostly broken down. Add olive oil, lemon juice, basil and salt and continue to pulse, scraping down the sides of the food processor or blender as needed, until well combined and smooth. Avoid over-blending, this can cause the basil to bruise and turn brown.

3. Use immediately or store in the refrigerator in an airtight container, covered with a thin layer of olive oil, for up to three days.

Two options:

Tip: Try swapping out pine nuts for walnuts or blanched almonds and basil for mint or arugula.

Next: Pesto, the Perfect Spring Food—and It’s Healthy Too

Pesto is perfect for something I call fridge foraging: using up those random bits in your fridge that need a dish to call home—stat. Ingredients like leftover fresh herbs, a stray bell pepper or the end of a bag of nuts or seeds come to mind. It’s also a nutritious, versatile sauce that will zhuzh up anything you add it to. For traditionalists, pesto is a sacred symphony of basil, parmesan, pine nuts, garlic, olive oil and salt, but try to see this as a jumping off point for a multitude of flavours and combinations. Master the pesto basics, then let your imagination run wild.

(Related: How to Grow Indoor Herbs and Veggies in Any Home)

Think beyond the garnish

Herbs provide the defining flavour in a pesto and, bonus, they’re super healthy. Herbs are actually an extension of the leafy green family, and like other leafy greens, herbs are high in vitamins A, C and K.

Many herbs, like basil, oregano, dill and cilantro, also contain polyphenols—plant compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Polyphenols can be protective against cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes: They may lower blood sugar and help to prevent blood platelets from clumping together, which can create a clot, narrow arteries and cause deep vein thrombosis, stroke and pulmonary embolism.

Sneak in other greens (or beans!)

No herbs? No problem. Using greens like kale, arugula and spinach is a great alternative. Not only will you be upping the nutrient content, it also provides an opportunity to use leftover greens (arugula stragglers, I’m looking at you). Don’t discount the tender greens attached to other vegetables, like beets, turnips and carrots: These are edible and are good candidates for pesto too. You can also add nutrients by blending in other vegetables and legumes, like roasted bell peppers, cooked zucchini, peas or edamame for added fibre and protein.

Keep it fresh

To make a flavourful pesto that will keep well, there are a few key things you should keep in mind. First, make sure you toast your nuts or seeds. Toasting until golden and fragrant heightens their flavour so nuts taste even more buttery and complex. My preferred method is to dry toast in a pan on the stovetop, where I can give them an occasional shake to nudge browning along. Nuts can turn the corner from golden brown to burnt quickly, and it’s harder to keep track when they’re in the oven. Once your nuts are nice and toasty, blitz them together with herbs, grated cheese, seasonings and oil to craft your pesto.

To keep your pesto bright green, use fresh, perky herbs—bruised herbs will lead to murkier pesto. Be sure to pat the herbs dry before use. To prevent browning in the fridge, cover the pesto with a thin layer of olive oil or press plastic wrap against the surface to make a barrier against oxidation. That being said, just because your pesto is more Oscar-the-Grouch green than a vibrant emerald doesn’t mean it won’t be tasty!

Use it on pretty much anything

Go off-script and think beyond basil to unlock infinite possibilities. Try using toasted pumpkin seeds, cilantro and lime juice, then spread it on tortillas to make breakfast burritos or drizzle it over tacos. Make use of the end of a jar of roasted red peppers or sun dried tomatoes: Blend them up with olive oil, toasted walnuts, anchovies and chili flakes for a flavour bomb of a pasta sauce.

Try spreading pesto onto bread for sandwiches or as the base of a pizza. Dot pesto onto the whites of your eggs just after they hit the pan for pesto-laced fried eggs. You can also add easy flavour to proteins like chicken breast or salmon filets by covering them with a layer of pesto just before roasting.

Add a little olive oil or lemon juice to thin out your pesto and you have a salad dressing. Or, stir a bit of pesto into yogurt, sour cream or mayonnaise for quick dip for crudité or to serve with smashed potatoes.

Any way you spread, dollop or drizzle it, pesto helps to make nutritious foods like greens, vegetables and lean meats more exciting. Let the fridge foraging begin!

Laura Jeha is a registered dietitian, nutrition counsellor and recipe developer. Find out more at ahealthyappetite.ca.

Next: A Spring-Perfect Recipe for Pea and Basil Pesto

Whether you’re fighting acne, hoping to give your complexion a glow or looking to even out your skin tone, you’ve probably tried or considered using trendy ingredients like vitamin C, retinol, glycolic acid and salicylic acid. All ingredients have their ideal uses (and work differently for different skin types), but can be harder to navigate because of their strong effects on the skin. Enter: Azelaic acid, an under-the-radar ingredient that’s well-tolerated by even the most sensitive skin and has a wide range of uses.

While the ingredient has been around for a while, it’s now making its way into more and more products on store shelves—with many brands adding the ingredient to new formulas.

We spoke with Monica Li, a Vancouver-based dermatologist and clinical instructor at the department of dermatology and skin science at the University of British Columbia, about azelaic acid to determine if it’s worth adding to our skin care routine.

What is azelaic acid?

“Azelaic acid is a naturally occuring form of dicarboxylic acid—it’s something that is naturally produced on our skin,” explains Li. It’s produced by a healthy? yeast that lives on our skin called malassezia furfur and has anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties.

What are the benefits of azelaic acid?

While your skin naturally makes azelaic acid, giving your skin more of it via skin care products can help you take greater advantage of its benefits. “At its prescription-level potency, it’s mostly used to treat acne and rosacea,” says Li. Because of its antibacterial properties, it can kill the bacteria on your skin that causes acne. And its anti-inflammatory properties help soothe rosacea, which often causes redness, swelling and acne-like breakouts.

Azelaic acid also has exfoliating properties. But, it differs from other acids like AHAs and BHAs because it’s gentle, so you avoid the dryness, redness and irritation that can come from harsher exfoliants. “It has a bit of what we call a keratolytic property, meaning it can unclog some of the debris that clogs up pores,” says Li.

The ingredient also works as a skin brightener and for managing hyperpigmentation because it inhibits something called tyrosine, which is an enzyme on our skin that produces pigment, says Li. “And because [azelaic acid] inhibits it, it can treat unwanted pigmentation on the skin and even skin tone.”

But its gentleness is its biggest draw, making it safe for people who normally wouldn’t be able to use comparable products. Li points to pregnant people or people who are breastfeeding as an example. Typically, pregnant people are told to cut retinol out of their skin care routine. But, “azelaic acid is safe in pregnancy, and it’s an option to explore if someone is dealing with pigmentation or acne when pregnant,” says Li.

How do I use azelaic acid?

As with all new skin care products, patch test on the back of your wrist or behind the ears a few days before applying to your face to make sure it doesn’t cause irritation, itchiness or other problems.

Then, start slow. While the ingredient can be used up to twice a day, morning and night, Li recommends introducing it to your skin care routine slowly, using it once a day, three times a week. Azelaic acid is considered gentle, but it’s still an exfoliant and it can take your skin time to get used to it. From there, you can gradually increase frequency if your skin is tolerating the ingredient well, meaning that your skin isn’t red, itchy or experiencing a burning sensation when you use it. If you don’t see results immediately, Li says that’s normal. It’s a very gentle ingredient so it’ll take at least six to eight weeks of consistent use to see effects.

Apply azelaic acid onto clean, dry skin as the first step of your skin care routine, before other serums. And Li reminds users to follow it with a moisturizer to “improve the tolerability of the product.” And, of course, don’t forget to protect your skin with a sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30.

Where can I find azelaic acid?

Just like any other skin care ingredient, azelaic acid is typically found in serums, creams and gels. It’s not as ubiquitous (yet!) but there are a few products in Canada that contain azelaic acid, all coming in different forms.

First, there are the prescription-level gels that derms can provide—the strongest potency in Canada being 15 percent, which is stronger than over-the-counter products and are for those using it as an acne or rosacea treatment, says Li. As for over-the-counter options, Drunk Elephant recently launched their Bouncy Brightfacial in Canada, a leave-on mask meant to clarify skin tone and fade spots that contains 10 percent azelaic acid. Paula’s Choice is has a 10 percent Azelaic Acid Booster. And, there’s SkinCeuticals’s Phyto A+ Brightening Treatment moisturizer, which includes a less potent dose with just 3 percent.

Is there anyone who shouldn’t use azelaic acid?

Of course, you should stay away from azelaic acid if you have an allergic reaction or a hypersensitivity to the ingredient, says Li. Or, if you’re someone who has severe cystic acne, “it’s unlikely that azelaic acid is going to do much. You’d need to talk to a doctor and get prescriptions that aren’t just topical.”

For those with sensitive skin or pigmented skin, Li advises caution when using azelaic acid because it could cause inflammation and post-inflammatory pigmentation. “The irritation causing skin inflammation stimulates melanocytes – cells that can produce excess pigment on the skin surface – and in more richly pigmented individuals, or anyone who isn’t fair skinned, these melanocytes are more easily activated,” she says. “I wouldn’t say you can’t use it, but be careful.”