Our Health Heroes

Think back to January 2020. We packed into bars and restaurants and Costcos. Commuting was still a thing almost everyone did. And a mysterious virus halfway around the world began making news. Then, everything changed. A global pandemic upended every aspect of our lives, the killing of George Floyd in the U.S. sparked a long-overdue racial reckoning within our own borders, and an already-looming mental health crisis was amplified. The good news: There are people who have shown, over and over again, they are willing to go the extra mile for the collective good. Here is a non-exhaustive but hella impressive list of everyday heroes who put extraordinary effort into our best health.

(Related: What Canadians Need To Know About the New COVID-19 Vaccines)

Clarice Shen, 25

For nursing Canada’s first positive COVID-19 patient

“I never felt scared. Everything just felt surreal.” That’s how Sunnybrook Hospital acute-care nurse Clarice Shen described her Jan. 23 shift, when she learned one of her Toronto patients was suspected of being infected with the novel coronavirus.

Shen had only been a nurse for three months, a career path she chose to pursue after reading a Reader’s Digest story about nursing efforts during the 2003 SARS epidemic. She has described being on the front lines as something she felt she was meant to do.

When testing confirmed that this was indeed Canada’s first COVID-19 patient, Shen, despite great uncertainty about the virus and how it was transmitted, volunteered to provide care. When the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic a few weeks later, Shen continued to care for COVID patients in the hospital’s dedicated unit. When interviewed on the news about her heroic efforts, Shen said she was simply doing her job. In a way, she is the face of the thousands of COVID-19 hospital heroes who confront the virus every day. —I.N.

(Related: 14 Virtual Care Services in Canada You Need to Know About)

Jenna Lyn Albert, 27

For using art to make essential commentary on health care

As Fredericton’s poet laureate, Jenna Lyn Albert is responsible for opening city council meetings with a poem. In September, after a lack of provincial funding forced the closure of an important LGBTQ2S+, women’s and family health clinic in the city, Albert chose a poem about abortion access. Response at the council meeting was mixed. While some criticized the poet for “politicizing” poetry, others supported the reading and noted that it’s the poet laureate’s job to provide cultural commentary and start important conversations in the community.

Clinic 554 was the only place outside the hospital that provided surgical abortions in the province. It was also known as a safe space for LGBTQ2S+ community members because of the clinic’s focus on transgender health care. Its closure has created a large health care gap in the province, not just for members of the LGBTQ2S+ community or people seeking abortions — 3,000 people are now without a family doctor.

In an interview after the reading, Albert said, “I think it’s always important to use whatever platform an artist may have to address issues that are really concerning the community.” —R.G.

(Related: What You Need to Know About Canada’s New Three-Layer Face Mask Guideline)

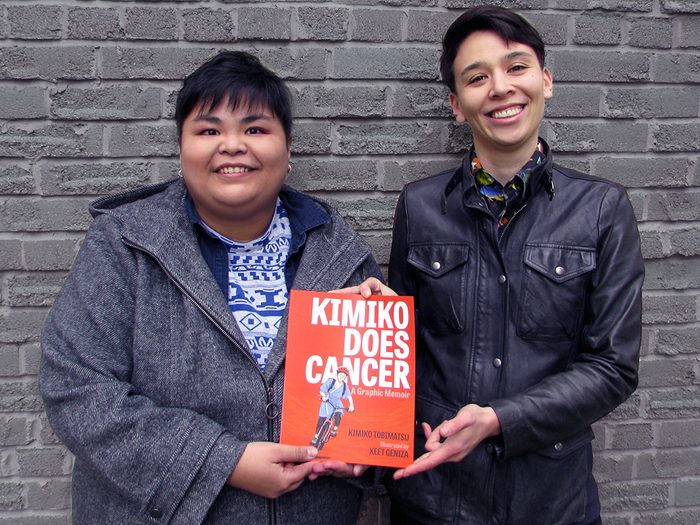

Kimiko Tobimatsu, 31, and Keet Geniza, 33

For telling a different story about breast cancer

When Kimiko Tobimatsu was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 25, she didn’t know anyone else her age who had gone through the same thing — let alone anyone queer and racialized. Mainstream depictions of breast cancer didn’t represent or resonate with Tobimatsu either: The images and awareness campaigns were all pink-washed, straight, white and feminine.

“When I was diagnosed, I wish I’d seen queers and trans folks and Black women telling their stories; I wish my doctors had understood diverse gender expressions; and I wish there’d been a whole lot more lobbying for equitable breast cancer care instead of courting companies for donations and selling blush-coloured water bottles,” she wrote in Refinery29.

Inspired by her experiences (and frustrations), Tobimatsu teamed up with illustrator Keet Geniza to create Kimiko Does Cancer, a graphic memoir telling the story of a young, queer, mixed-race woman and her experiences with the physical and emotional realities of breast cancer — this time, without looking through pink-coloured glasses. —R.G.

Karene-Isabelle Jean-Baptiste, 46

For spotlighting Black women in health care

In June, Montreal-based photographer Karene-Isabelle Jean-Baptiste posted a portrait on Instagram of nurse Barbara Petit-Frere surrounded by flowers. “Montreal was one of the hot spots of the COVID-19 pandemic. Black women were and continue to be deeply invested,” Jean-Baptiste’s caption reads. “I wanted to share some of those faces with you.” That picture launched the Black women in health-care project, which aims to highlight Black health-care workers labouring at the front lines of the pandemic.

Jean-Baptiste’s interest in the project came from knowing that many in her community did not have the privilege of staying home — they were working to keep people safe. “It got me thinking, Are we telling the stories of these people who are, in a way, sacrificing themselves? There’s a human aspect of it I really wanted to outline,” the photographer said in an interview with CTV news.

The bright, colourful portraits depict the workers in their uniforms—often outside, usually masked—as well as in “an outfit that they feel fabulous in.” That way, it’s not just their contribution to healthcare being celebrated, but their identity outside of work. —R.G.

(Related: The Forces That Shape Health Care for Black Women)

Samanta Krishnapillai, 29

For launching the ON COVID-19 Project

When the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, Samanta Krishnapillai, who had recently completed a master’s degree in health information science, noticed an information gap.

Using her personal Instagram account, Krishnapillai, who describes herself as an “equity-oriented health scientist,” began answering questions about COVID-19 in plain, accessible language. As her followers grew, she realized she was on to something, and enlisted the help of more than 100 volunteers between the ages of 18 and 35 to create the ON COVID-19 Project. The online resource aims to disseminate credible, concise and Canadian-focused information over social media.

Posting two or three times a day, the ON COVID-19 Project explains everything from the Spoon Theory (a metaphor that helps illustrate how people live with a chronic illness) to how to have COVID-19-safe holiday celebrations. As the pandemic stretches on, Krishnapillai, who is from Markham, Ont., plans to keep the project going. “We’ve gotten such great feedback from people, thanking us for explaining the pandemic in a way that is easy to understand.” — I.N.

(Related: What You Need to Know if You’re Delaying Pregnancy During Covid)

Lara Gurney, 42

For creating Vancouver General’s “wobble room”

As the head nurse educator for Vancouver General Hospital’s emergency department, Lara Gurney saw first-hand the toll COVID-19 was taking not just on patients but also on health-care staff. “People were coming in feeling anxious even before their workday had started,” she said in June.

Inspired by spaces created in U.K. hospitals, Gurney created a “wobble room”: a place for staff to scream, cry, meet with a counsellor over Zoom or simply relax and take a time out from reality.

Having studied compassion fatigue and burnout among health-care workers, Gurney said she hoped the room would improve the safety and wellness of staff, who were facing unprecedented and overwhelming conditions. It was her way, she says, of telling her colleagues, “You’re not alone, and you don’t have to be alone.” —I.N.

(Related: ‘The Pandemic Is Changing How We Die. I’ve Seen It Firsthand.’)

Sané Dube, 35

For helping close the racial health gap

As a community health policy leader, Sané Dube knows that Black communities in Toronto and across Canada are facing two health emergencies right now: COVID-19 and anti-Black racism. So she spent the year urging governments and health-care providers to help do something.

In her work as the policy and government relations lead at the Alliance for Healthier Communities, she called for anti-Black racism be declared a public health crisis. In June, Toronto Board of Health did just that.

By advocating strongly for race-based data collection in Toronto, Dube also helped show that Black and racialized communities were hit much harder by the pandemic. Next up: She’ll help knock down barriers to health in her new role as community policy manager for the University Health Network.–O.B.

Dr. Ameeta Singh, 54

For waging war on STIs

Dr. Ameeta Singh, an associate clinical professor at the University of Alberta in the department of medicine, specializes in sexually transmitted infections. This year, she was part of a project that looked to provide rapid point-of-care tests for HIV and syphilis.

Alberta has the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country, and women (often Indigenous women) struggling with housing security or mental health issues are disproportionately affected, Singh says. Faster diagnosis means faster treatment, which can stop transmission to partners or unborn babies, and prevent the infection from creating more serious complications.

Singh has also been trying to secure funding for a program called Pregnancy Pathways, which helps find stable housing for homeless women who may have addiction issues. –O.B.

Dr. Onye Nnorom, 39

For leading education on systemic racism

Dr. Onye Nnorom is a leader committed to pushing public health institutions to take action on racism linked health inequalities that disproportionately affect Black communities. She’s also a family doctor and associate program director at the University of Toronto who leads the Black health curriculum at the school’s faculty of medicine.

Nnorom created a health curriculum that teaches medical students about systemic racism within the Canadian health-care system to better ensure future physicians practise with anti-racism in mind. She’s also the president of the Black Physicians’ Association of Ontario and launched her own podcast this year called Race, Health and Happiness, in which she interviews guests about tackling institutionalized racism in order to achieve their goals. —O.B.

(Related: Black-Female-Owned Wellness Businesses to Support Now and Always)

Dr. Stephanie Hiebert

For leading an all-female transplant team

When Dr. Stephanie Hiebert, a Halifax-based surgeon, stepped into the operating room this year, she noted something different about her team of seven. They were all women.

According to the Nova Scotia Health Authority, this all-female transplant team was a first for the province — and maybe a first for Canada. Working alongside Hiebert, the transplant team consisted of a general surgery resident, two anesthesiologists and three nurses.

Hiebert is the only female liver transplant surgeon in Nova Scotia, and one of the few in the entire country. “I think we’ve come a long way in the past couple of decades with women going into surgical fields,” Hiebert said on a radio show earlier this year.

“I think there are still areas of surgery that are less appealing to women and still more dominated [by men], and certainly transplantation is one of those fields. But we’re coming.” —R.G.

(Related: How a Front-Line Anesthesia Resident Is Avoiding Burnout During the Pandemic)

Dr. Susy Hota, 43

For preventing outbreaks in health-care settings

Dr. Susy Hota has had a busy year. As the medical director of Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) at Toronto’s University Health Network — a system that includes two busy hospitals and a cancer centre — Hota is in charge of helping prevent virus and disease outbreaks in health-care settings. The COVID-19 pandemic made this a year like no other.

Hota and her IPAC expanded their mandate to work with long-term care and retirement homes to help protect residents. Long-term care homes saw some of the deadliest outcomes at the height of the pandemic, shedding light on both how ill-equipped many of these facilities are to manage the disease and how quickly it spreads through them.

Hota’s extremely active on Twitter and in the media, helping sort through and decode often conflicting COVID information. She’s also an associate professor at the Temerty faculty of medicine at the University of Toronto, shaping the infectious disease experts of tomorrow. —L.H.

(Related: What the Anti-Mask Movement Needs to Know About COVID-19)

Alison Houweling, 47

For helping people with substance-use disorders stay safe

Alison Houweling, a harm-reduction counsellor at the Cammy LaFleur Street Outreach Program in Vernon, B.C., has seen the dangerous intersection of an opioid crisis and a global pandemic play out in real time.

In October, B.C. reported more than 1,200 fatal drug overdoses so far in 2020 — up from a total of 983 deaths in 2019. Houweling’s outreach work has never been more vital. “The distinction between our COVID-19 response and our opioid overdose crisis response is telling,” she says.

“With COVID-19…we all saw how quickly our social systems can be proactively changed to ensure the safety and security of our people. With the opioid overdose crisis, people seem to be still scratching their heads.”

Houweling got into harm-reduction work because she wanted to help others — something she learned from her parents, who always made a point of assisting the less fortunate. Despite the hardships of the pandemic, Houweling says this year has made people come together to find ways to support people with substance-use disorders while staying safe. “We participated in many Zoom meetings to coordinate services and ensure nobody was left behind.” —L.H.

(Related: How a Psychotherapist Does Her Job Through Zoom During Quarantine)

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa, 27

For setting the stage for better representation in medicine

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa, a recent graduate of the University of Toronto’s faculty of medicine, has her sights set firmly on systemic racism in the health-care system.

Black Canadians routinely face barriers to care, report higher levels of diabetes and heart disease, and are more likely to have their pain overlooked. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted racial health disparities, as a disproportionate number of Black Canadians have been affected by the disease.

Oriuwa, who entered med school as the only Black student in her class of 259, has worked tirelessly with U of T’s Black Medical Students’ Association and the Black Student Application Program to set the stage for better representation in medicine. Their efforts are working: 24 Black students were accepted to U of T’s med program in 2020, the largest cohort in the school’s history.

Oriuwa was named valedictorian of her graduating class, only the second Black woman to hold the title at U of T’s faculty of medicine and the first woman in 14 years to do so. “We had a vision of 2020,” she said in her speech, “and though the picture didn’t quite turn out as clear as we thought it would be, we remained a class of visionaries.” —L.H.

(Related: Michelle Obama Talks About Having “Low-Grade Depression.” Do You Have It Too?)

Dr. Juveria Zaheer, 38

For transforming the way we understand suicide

As a clinician scientist at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health’s emergency department, Dr. Juveria Zaheer deals with people in the midst of a mental health crisis, usually on the worst day of their lives.

Her commitment to patient care and her integrated approach to suicide prevention strategies for all people — across gender, age, diagnosis, immigration status and ethnicity — are part of why she was named to Canada’s Top 40 Under 40 in October. Two years ago, Zaheer published a first-of-its-kind study in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry analyzing the language of suicide notes.

Her ongoing research focuses on understanding suicide risk and incorporating patients’ and families’ experiences to co-create interventions that work.

“Suicide is such a tragic end to someone’s story, and it not only affects the person whose life is cut short but also their family, their friends and their community,” she said in a recent statement. “It’s this incredible tragedy that we don’t talk about and have difficulty processing, and everyone’s cultural context makes this experience different.”— R.P.

(Related: How One Woman Manages Her Mental Health in Quarantine)

Founders of MyPlan Canada

For creating an exit plan for abused women

In Canada, one in three women will experience intimate partner violence at some point in their lives. In response to these statistics, a group of researchers at Western University, the University of New Brunswick and the University of British Columbia developed and tested MyPlan, an app that helps women experiencing intimate partner violence make decisions about their safety, health and well-being.

Discreet and private, MyPlan draws on scientific research and was tested with people experiencing intimate partner violence, their friends and violence service providers. The app, which is also available as a browser-based service, has a quick exit function that protects user privacy by letting users to promptly close and lock the app. Users can also input their specific circumstances (like whether there are children at home or if they have access to a vehicle), and the app will walk them through a plan to protect themselves. —R.G.

Next: The Ultimate Guide to Staying Active Outdoors This Winter