It’s Worthwhile to Start Thinking About Your Vagus Nerve

You’ve probably never even heard of your vagus nerve. (That’s okay: It’s new to us, too!) But it could be the key to lowering your risk of high blood pressure, managing depression and even scoring a better night’s sleep.

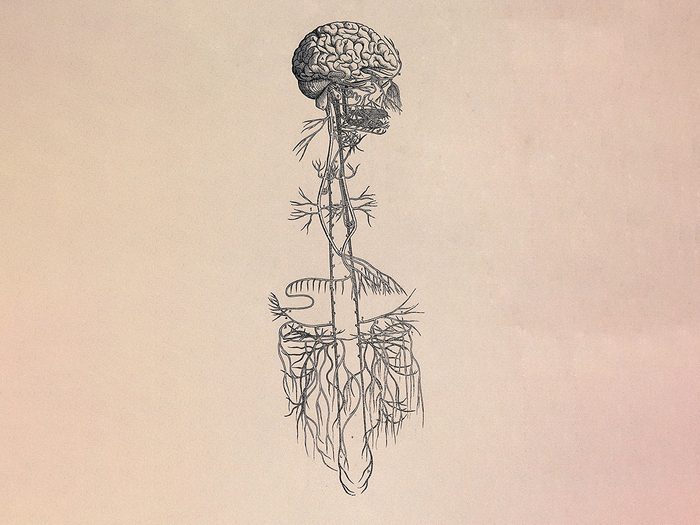

The longest cranial nerve in your body, the vagus nerve begins just behind your ears and travels down both sides of your neck, across your chest and through your abdomen. It takes its name from the Latin vagary, because this bundle of nerve fibres literally “wanders” through your body, connecting your stomach, lungs, heart and other organs with your brain. The vagus nerve is involved with everything from speech, eye function and facial expressions to blood pressure and mood.

“The vagus nerve is like a conductor that orchestrates the fight-and-flight and rest-and-digest centres of the brain,” says Krista Roesler, a registered psychotherapist and co-founder of Psych Company in Toronto. This is what makes it so integral to our mental health and emotional wellness, she adds, because it helps us regulate our feelings and it triggers the relaxation response after times of stress.

Maintenance for the vagus nerve anatomy

How do you know if your vagus nerve needs some special attention? Depression, anxiety, breathing issues, slow heart rate, digestive problems and low blood pressure are potential signs of poor vagal tone, which is just a way of describing how well the nerve is working. One measurable indicator is heart rate variability, or the fluctuation in heart rate between when you inhale and exhale. Another indicator is how quickly your heart rate comes back down after an intense jog or Peloton ride. (The number is captured by many health trackers, including the Oura Ring and Apple Watch.) Simply, the shorter your recovery time, the better the odds that your vagus nerve is in good shape.

Practising deep breathing will jump-start your body’s relaxation response, says Roesler: Think alternative nostril breathing, deep diaphragmic breath cycles, meditative humming and chanting. Cold therapy, which could be a Wim Hof-style plunge into ice water, a minute spent under a cold shower or an ice pack on the back of your neck, will kick-start your parasympathetic nervous system, exercising your vagal tone. Walking, jogging and other forms of regular activity also strengthen your vagus nerve. And so does social support. “Surrounding yourself with people who make you feel safe and secure, hearing a loved one’s voice, laughing, kissing, cuddling a pet—these can all balance your nervous system,” Roesler says.

Stimulating the vagus nerve

Vagus nerve stimulation (or VNS) is a tool that doctors use to treat a wide range of diseases and disorders. One method involves a small medical device surgically implanted in the chest that sends tiny electrical pulses through the nerve. “It’s used therapeutically to reduce symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders, PTSD and treatment-resistant depression,” says Roesler.

A similar form of VNS therapy is also used to treat refractory (medication-resistant) epileptic seizures. “It’s almost like a pacemaker for the brain because it interrupts the abnormal brain activity that causes seizures,” says Dr. Paula Marques, a neurologist and epilepsy genetics fellow at the Krembil Brain Institute, part of Toronto’s University Health Network. “About 30 to 40 percent of all epilepsy cases are refractory. In about 50 percent of those cases, the VNS could bump up the medication’s efficacy by 50 percent, which makes a huge difference in a patient’s life.”

The applications for VNS don’t end there. There are studies underway to determine its potential for treating Alzheimer’s, autism and rheumatoid arthritis. In February, Health Canada approved a non-invasive clinical procedure to be used in hospitals to treat acute respiratory distress due to COVID-19. And there is a recognized non-invasive hand-held neuromodulation device that migraine sufferers can use at home to fight off cluster headaches.

What happens in vagus

“There are added benefits to VNS therapy that my patients report,” says Dr. Marques. “Many say they feel more alert and more upbeat.” That’s because the vagus nerve will prompt the body to release feel-good chemicals and activate focus centres in the brain that help with clarity.

DIY devices are now popping up, promoting better stress management, deeper relaxation and more tranquility. Apollo, a wearable that goes around your wrist (like a smart watch), provides a type of touch therapy using silent vibrations and describes itself as a “workout for your nervous system.”

And then there’s a set of high-tech earbuds, called Xen by Neuvana, that send stimulating micropulses through the left ear canal to tap the vagus nerve. Because the vagus nerve signals the brain to release calming neurotransmitters like serotonin, one of the most sought-out benefits of the device is better sleep. Some users pair it with a favourite sleep meditation app at lights-out for the ultimate bedtime routine.

Alina Butunoi, a massage therapist and certified movement neurology specialist with Align for Performance in Ottawa, uses the Xen earbuds in her practice when working with her clients. “Performing a session with Xen for 15 minutes prior to training allows us to reignite the signals for the vagus nerve,” she says. It’s a tool she employs alongside progressive relaxation and breathing techniques, and traditional massage and mobility exercises. She says it’s helpful with both pain management and rehabilitation.

Without good vagal tone, we are prone to prolonged periods of high stress, which is detrimental to our health. In addition to the physical stressors, we can have difficulty managing our emotions, overreact, have trouble concentrating and lack compassion and joy. “It’s hard for us to cope and handle life in this state,” says Roesler. Imagine, instead, a lake that is calm and serene. The sediment and debris have floated to the bottom, and you can see clearly through the water. “This is how we want to see the world and our problems,” Roesler says. In a way, a well-functioning vagus nerve can serve as our goggles.

Next: Food for Thought: Can What We Eat Influence Our Mental Health?