This Ultramarathoner and Mom Is Bringing Reconciliation to the Trail-Running World

Maggie Wilson wants all runners to know—and honour—whose land they’re racing on.

I want to play that game. That’s what 45-year-old Maggie Wilson thought the first time she heard someone mention ultramarathons. It was a big leap. Though she was a former high school track athlete, her longest run up to that point was 1,500 metres, which takes about five minutes to complete. The shortest ultra-distance is typically 50 kilometres—a minimum of six hours straight of running.

Wilson started working with a coach and in 2016, she finished Broken Goat, a 50-km race in Rossland, B.C., in eight hours and 18 minutes. After a couple more years of training, a 50-miler in Squamish and adding a fifth kid to her blended family (she continued to run during her pregnancy), Wilson helped establish the Raven 50 Mile Ultra and Relay in Whitehorse.

Initially, Wilson says she ran ultramarathons because she loved pushing herself, suffering through, then slamming the finish-line beer and sharing battle stories with other runners. She still likes the physical challenge, but now, it’s about a lot more than merely testing herself. “I think, ultimately, joy is still what I’m chasing, only I’m maybe not as naïve as I was a few years ago,” she says. “There’s some other variables I need to feel good about a race now.”

One of them is whether organizers honour the history of the race route. Her partner—a film director and cinematographer who also took the photos for this story—is Haudenosaunee, as is their toddler son, Ohkwá:ri. The last couple years have made her think about her place as a relative newcomer who moved to the Yukon as an adult, after growing up in Kenya, France and the Philippines (her parents were in the Foreign Service). She also thought about her role as a white woman in the trail-running world, often racing over land that is the traditional territories of Yukon First Nations.

When the Raven was established in 2017, it was called Reckless Raven, a name arrived at by its founders over beers in a Whitehorse bar. (They were drinking a local beer called Reckless Abandon.) For the first few years, Wilson volunteered to sweep—following at the back of the pack to make sure no racers were left behind—or with the medical team. In the third year, she stepped away, after reflecting on her own values around running. She was feeling sheepish about her role in founding the race. “We literally named a race in settlement land after a beer,” she says. “It can’t really get more colonial than that.”

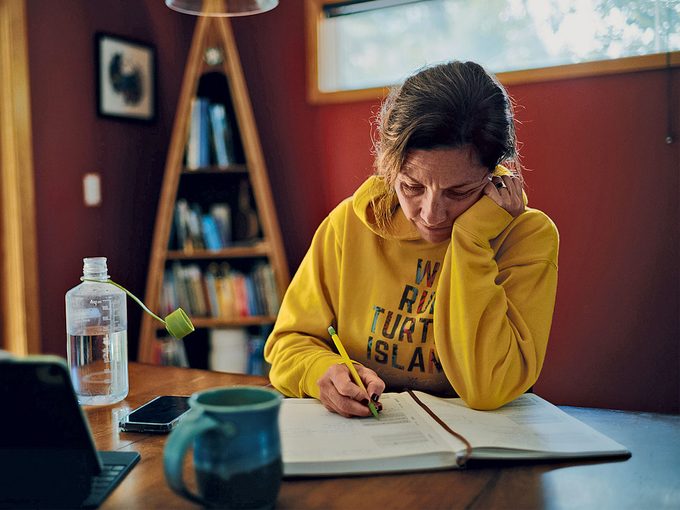

Last year, while working on a Master’s degree in applied neuroscience, she got an A on an op-ed paper she wrote for a social work class about running and reconciliation. Her partner congratulated her on the grade, then asked her what she was going to do about it.

After the Raven’s race director read the op-ed, he asked her to take the lead on community engagement and reconciliatory efforts. She introduced changes such as renaming the race and redesigning the logo with an Indigenous artist.

Wilson no longer wants to drop into mountain towns, collect her medal and leave. She’d rather connect with the local people and understand the communities where she’s competing. That’s what she wants to build into the Raven too, so it’s more than a destination race. It should be something that opens a door, invites runners in and tells them, “This is who we are.”

Parts of the Raven 50 Mile Ultra and Relay are inaccessible by vehicle, so aid station supplies are brought in on horseback for those sections. Runners must carry food and one litre of water, plus a toque, mitts, jacket, whistle, cell phone and an emergency survival blanket, so that racers are prepared if they need to wait a long time for a helicopter evacuation.

Wilson rises at 4:30 a.m., before anyone else is awake. She takes half an hour to drink coffee, then turns to her calendar to figure out family logistics (the kids range from two to university age). “Having a large family is like multi-project management,” she says. She finishes her solo time with light stretching, breathwork and meditation.

The outdoor running season in the Yukon is short: Even in June, you can still find yourself running in snow from the previous winter. By late August, snow usually dusts distant mountain peaks again.

“I work in a field that’s pretty heavy,” Wilson says. As a family support worker with the Kwanlin Dün First Nation, she says that taking time for yourself is key to avoiding burnout. “For some people, it’s a glass of wine. For other people, it’s their beading. For me—in order to do this work and stay healthy—I need to run.”

Fortunately, her co-workers get it. That’s why Wilson has arranged to take Wednesdays off. After she drops her youngest at daycare, she can disappear into the mountains for long runs of up to eight hours.

When the weather and seasons allow, Wilson prefers running on winding mountain routes instead of downtown Whitehorse’s flat city streets. Trails are easier on your body than roads, and being in the bush with no one else around makes her feel more connected—to herself and to the land.

In addition to renaming the race, Wilson made sure the Raven’s social media posts were explicit about their new direction. The race guide was re-written and vetted by Kwanlin Dün First Nation citizens, and she’s looking to organizations like ReNew Earth Running for concrete actions that go beyond land acknowledgments.

Wilson trains five days a week for about 10 hours total. (But if she’s building distance for an upcoming race, it’s sometimes more.) She logs plenty of hours in her home gym and many kilometres inside on her treadmill. Sometimes, working out when her kids are sleeping is the only way to fit everything into her schedule.

This year, the Raven fell on Wilson’s birthday, and at the last minute, after her volunteer duties were complete, she decided to join in for part of the race. She missed a turn and had a close encounter with a bear, but still managed 27 miles in about 6.5 hours. The next day, she hopped on a red-eye flight with her toddler in tow.

Next: Meet Sisters Sage, an Indigenous Wellness Brand Reclaiming Smudging