The most common knee injuries and how to prevent them

Unfortunately, knee injuries are on the rise. Here’s how to keep your body’s largest joint healthy and pain-free

Source: Best Health magazine, September 2014

Like tires on a car, knees are designed to support and help transport our body weight. If we increase the load, we increase the risk of wearing them out. In fact, every extra pound above a healthy weight equals three additional pounds of pressure on knee joints when we walk, and an extra 10 pounds when we run.

Unfortunately, knee injuries are on the rise in children and teens, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. And knee pain in general is also increasing among adults under age 65. That includes pain from osteoarthritis (OA), the most common type of arthritis, which occurs when protective cartilage on the ends of bones wears down, causing joint pain.

‘Obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for knee osteoarthritis,’ says Dr. John Theodoropoulos, head of orthopedics at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto. ‘However, it doesn’t entirely explain why knee pain is on the rise. We suspect it is because people are demanding more out of life.’

Women have two to three times the rate of knee injury compared to men; one reason could be that during the menstrual cycle, there are changes in the way the brain controls the muscles that ensure the kneecap glides correctly in the joint, according to 2012 research from the University of Texas at Austin. There are also neuromuscular, structural, musculoskeletal, biomechanical and even hormonal differences that increase our risk.

Here’s an in-depth look at three of the most common injuries.

ACL tears

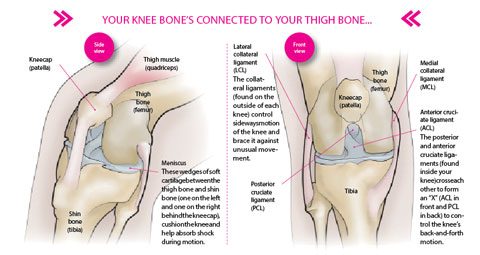

A tear or sprain of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tends to occur between ages 15 and 45, when people are likely to be more active. The ACL ligament prevents the shin bone from sliding out in front of the thigh bone, and provides stability to your knee. An ACL injury can occur in one of three ways: when the ligament is stretched (a grade 1 sprain); when it is stretched so far it becomes loose (a grade 2 sprain or ‘partial tear’); or when it splits into two pieces (a grade 3 sprain or ‘complete tear’). Injury can happen with motion that creates untenable pressure between the thigh and shin bones, such as changing direction rapidly or landing incorrectly after jumping. If you sprain or tear your ACL, you may hear a ‘popping’ noise, or feel your knee give out on you. Other symptoms can include pain, swelling, loss of motion, and discomfort when walking.

According to research, OA will develop in more than 50 percent of people with ACL tears within one to two decades after injury.

Who’s at risk?: Women have a higher risk of ACL tears than men, says Theodoropoulos, and this is especially true in jumping and pivoting sports such as soccer, Ultimate Frisbee and basketball. There are various theories for this (for example, some women may have stronger quadriceps in relation to their hamstrings). But all of the theories need further investigation, says Agnes Makowski, a sports physiotherapist in Toronto and spokesperson for Sport Physiotherapy Canada, a division of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association. She says other risk factors include having a history of knee injuries that were not well treated, and playing sports on artificial surfaces (which increase friction and cause the foot to stop abruptly).

Prevention: Anyone who is at risk, including developing athletes, can reduce their risk of ACL tears and subsequent OA by improving their neuromuscular control, says Theodoropoulos. Neuromuscular control exercises are designed to raise one’s awareness of body position, alignment and balance reactions; and strengthen relevant muscles to promote knee control in daily activities and sport-related tasks such as landing from a jump. A physiotherapist can suggest appropriate exercises.

Recovery: Treatment recommendations will vary depending on age and needs. Surgery is often required to treat a torn ACL, but non-surgical treatment (bracing and physical therapy) may be effective for restoring function and strength for those people who have low activity levels (for example, the elderly) and who don’t wish to undergo surgery.

Runner’s knee (patellofemoral pain)

This is a term used to refer to several factors that cause pain around the patella bone located at the front of the knee. This can include improper alignment of the kneecap (knock knees, for example), previous injury, flat feet or weak thigh muscles.

Patellofemoral pain is typically the result of overuse. Sometimes it is due to a degenerative condition caused by a softening and breaking down of the cartilage behind the kneecap over time’this is known as chondromalacia patella.

Who’s at risk?: Suggested risk factors include certain anatomical features such as less optimal hip and kneecap alignment angles, muscle imbalances around the hip and knee, overtraining and inadequate recovery, says Makowski.

Prevention: Women can counter the natural imbalances that put abnormal stress on the knees by maintaining a healthy weight, stretching before and after exercise, using proper running form, and strengthening hip abductor and glute muscles, says Rick Kaselj, a practising kinesiologist in Surrey, B.C. (Get suggested exercises here.)

Recovery: Stop activity and follow RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevation). After the pain and swelling have passed, reconditioning exercises (prescribed by a physiotherapist) can help you regain full motion, strength, endurance, speed, agility and coordination. Surgery may be required to remove damaged kneecap cartilage, or to realign the kneecap.

Meniscus tears

There are two menisci in each knee; both are wedge-shaped pieces of cartilage that act as shock absorbers between your thigh bone and shin bone. You might feel a ‘pop’ when you tear a meniscus (pain may or may not be present), but most people can keep walking afterwards. Over the next two or three days, swelling and stiffness of the knee may slowly result.

Who’s at risk?: Anyone can suffer a meniscus tear. Those who play contact sports such as hockey are more likely to tear the meniscus, although any sudden squatting and twisting of the knee can cause the damage. Risk increases with age, since cartilage weakens and wears thin over time. A piece of meniscus may come loose and drift into the joint, resulting in a ‘locking’ or ‘buckling’ of the joint. Improper treatment for a past knee injury, or failing to properly rehabilitate an injury to the knee, can also increase risk, says Makowski. ‘If you’re dealing with a knee condition, it’s a good idea to get assessed by a trained practitioner [such as a physiotherapist], who can determine any risk factors, assess your current status and provide appropriate exercises to address muscle imbalances and prevent future reinjury.’

Prevention: Meniscus tears, although common, can be prevented by warming up and stretching before activity. Since obesity is a leading cause of OA, and knee pain in general, maintaining a healthy weight is a good strategy to prevent knee conditions, says Theodoropoulos.

Recovery: Stop activity and follow RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevation). Tears can heal on their own, but some may require surgery to trim away pieces that cannot heal.

What is "water on the knee"?

This is an accumulation of excess fluid in or around the knee joint. It can be the result of trauma, overuse, injury or an underlying condition such as arthritis. Once your doctor determines the cause (by draining some fluid and then testing it, or by other methods such as a blood test), the appropriate treatment will be decided.

Knee replacements

In Canada, 90 percent of knee replacements are done because of irreparable damage caused by OA. Most replacements last between 10 and 15 years, at which time you may require a second replacement, also known as revision surgery. The younger you are when you have a knee replaced, the more likely it is that you will need revision surgeries. Knee replacements are covered by provincial healthcare plans; however, there are wait times. (According to Canadian benchmarks, those wait times are supposed to be no longer than 182 days/six months, but in reality can be longer.)

This article was originally titled "Healthy knees, please!" in the September 2014 issue of Best Health. Subscribe today to get the full Best Health experience’and never miss an issue!