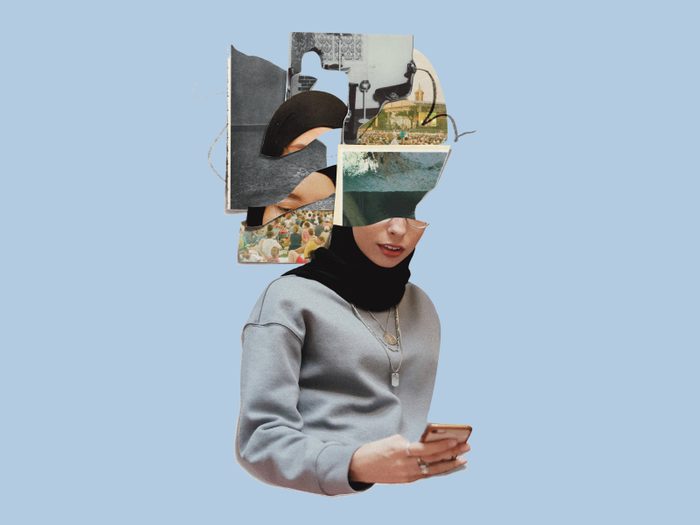

How the Pandemic Changed How We Feel When We Feel Left Out

The new FOMO: This is why missing plans is more anxiety-inducing after lockdown.

FOMO crept back into my life in the most predictable way imaginable: I was scrolling through Instagram. The offending post was a photo snapped at a backyard birthday party. My first thought was, Wait, why wasn’t I invited? Followed by the most intense sense of FOMO I’ve ever experienced.

Fear of missing out, or FOMO, was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2013, though the phrase was created in 2000 by, no surprise, a marketing strategist. FOMO is a form of social anxiety that feels like a nagging, all-consuming sense that you’re missing out on something—plans, in-jokes, even a “better” experience than the one you’re currently having are all fair game for FOMO. While it ruled the social dynamics of pre-pandemic life (a University of British Columbia study found that 48 percent of those studied believed their friends had more friends than they did), it seemed like during the pandemic, FOMO took a back seat.

(Related: Introducing the Brand New and Not Improved Post-Pandemic Me)

It made sense: During the pandemic, we were told that the best thing we could do for ourselves and our communities was stay home and “miss out” on normal life. During lockdown, people even started embracing JOMO, or the joy of missing out. But, as we slowly come out of the pandemic, it feels like FOMO is back. And, if my backyard birthday party reaction is any indication, it’s stronger than ever.

The more I ruminated on that gathering, the deeper I delved into an impenetrable mental maze. I wondered why I even felt FOMO, especially after a whole year of declining any invitations for face-to-face plans. Then I agonized over whether I even wanted an invite in the first place—besides, I hadn’t talked to these people since March 2020.

Finally, I did something I had never done before: I counted the people who were there. If there were 10 people at the party, they couldn’t have invited me—that would make the event too big, I rationalized to myself, remembering that Ontario’s outdoor gathering limit was capped at 10 at the time. Unfortunately, this rationale was another mental maze dead end: I began stewing over the fact that I didn’t make this person’s top 10.

It turns out that not only is FOMO back with a vengeance but there’s also a whole host of new things that affect how we socialize and that contribute to post-pandemic social anxiety.

(Related: 8 Women Share the Impact the Pandemic Has Had on Their Mental Health)

First, there’s more to think about whenever you’re making plans. All these extra considerations—vaccination status, government restrictions, individual comfort level—can make planning extremely overwhelming. “If we had been born into this, and it had gone on for a decade, it wouldn’t be as hard to manage because we’d have so much experience doing it,” says Allison Ouimet, an associate professor of clinical psychology at the University of Ottawa. “But this is all new. We haven’t figured out how to get through it yet.”

Everyone has a different approach to COVID-era socializing. For example, if I go to a public patio, will my more cautious friends be mad at me for not being as careful as them? Or, what if I’m the cautious one—will my friends be upset that I don’t want to hang out? “There’s going to be a fair amount of anxiety over people’s boundaries,” says Ouimet. “That can create conflict and anxiety about conflict.”

Then there’s the fact that we just haven’t done the whole socializing thing in a while. According to Ouimet, it’ll take some time to build up those socialization muscles to where they were pre-pandemic. “We’ve all been living an introvert’s life for the past year and a half, so when we go back out to seeing lots of people, it saps our energy,” she says. Since we’re out of practice hanging out offline, we aren’t used to all the additional stimuli: other real human beings, the environment we’re in, trying to think about when to cut in to the conversation. It’s overwhelming when you haven’t had to pay attention to that much stuff in a while.

(Related: Going the Distance: How Covid Has Remapped Friendships)

Luckily, Ouimet believes most of us will reacclimatize soon. “In three or six months, we’ll have figured out how to handle this,” she says. But right now, we’re in this in-between phase where everyone’s got different beliefs, emotions and reactions to reopening, and we don’t quite have the tools to navigate those differences just yet. “It’ll feel really, really awkward and weird and hard at first, but I think it’s going to get really easy quickly—we’re going to fall right back into who we were before the pandemic, socially.”

For now, as we stumble through this awkward moment between lockdown and the “new normal,” Ouimet says we should cut ourselves a bit of slack. “It makes sense that things are harder,” she says. Show yourself some compassion and forgiveness rather jumping to criticize yourself for how you’re feeling.

To transition back into socializing, Ouimet suggests starting with naming your fears to nail down what you’re anxious about. “When we feel anxious, it’s this big jumble of thoughts and feelings and emotions and physical sensations, et cetera,” she explains. Once you’ve pinned down why you’re feeling anxious, take a small step outside your comfort zone. Maybe you’re not ready for a restaurant patio, but you could have some friends over in your backyard, for example. These small, incremental steps will ease you back into socializing at pre-pandemic levels while still accepting your own boundaries, says Ouimet. “And, over time, the more we do things a little bit outside our comfort zone, the more comfortable we’re going to feel doing them.”

While I’m ready to be back where I was pre-pandemic—making plans on a whim as opposed to fighting FOMO while also avoiding the social stress of initiating plans—I hope I can bring some of the JOMO I leaned into during lockdown. I don’t want to stress over being Friend #11 anymore.

Next, this is how to cope with the anxiety of the post-pandemic world.