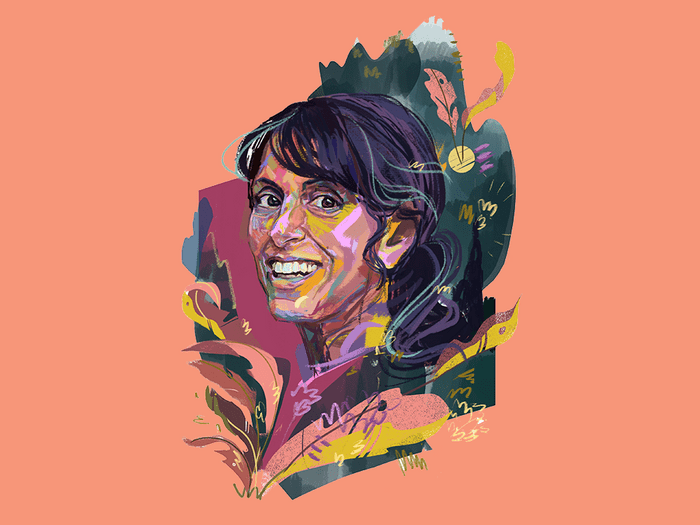

How The Pandemic Started New Conversations About My Parkinson’s

I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease at 28. During the pandemic, my family started having more open communications about my condition.

Recently, my family and I ventured north of our home in Ajax, Ont., to the Bruce Peninsula to go hiking at Greig’s Caves. The website for this natural attraction describes 10 limestone caves nestled in an environment of “peace and tranquillity”—but also warns, with a “caution” sign on its home page, that the trail is challenging.

My family wasn’t always into hiking. Like so many others, wandering the outdoors, and even traipsing around in the winter snow, is a hobby we adopted during the pandemic. It was a way for us to get out of the house and be together as a family. It also had a happy side effect of helping my Parkinson’s disease symptoms by improving my balance and mobility, and reducing my slowness and rigidity.

There’s a misconception that Parkinson’s is an old person’s affliction. But this neurodegenerative disease, which 25 Canadians are diagnosed with each day, knows no boundaries in terms of age, ethnicity, race or geographic location.

(Related: Where’s Your Head At?)

I was only 28 when I noticed a tremor in my right pinky finger. I had just finished my residency and was starting a new family practice. I was also pregnant with my first child, and as a physician, I knew my symptoms were not pregnancy related.

When I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, my initial reaction was denial. I spent the first decade of my diagnosis busying myself with busyness to avoid dealing with the disease. I would look at my day, and if I had pediatric vaccinations scheduled, I’d time my Parkinson’s medications accordingly so I wasn’t shaking while administering shots. I wanted to do my job without Parkinson’s interfering. But that can only last so long.

Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative disease, meaning it’s a brain disease that gets progressively worse—and since there’s no cure, the only thing you can do is manage your quality of life. I was a bad patient, as many physicians are, and eventually, I reached a point where that wasn’t an option anymore. I wasn’t sleeping. I was overmedicating, trying to control my symptoms, as well as the numerous drug side effects. I had gone from happy-go-lucky to pessimistic.

My neurologist told me I had a choice: I could either walk out of my office or crawl out, but I couldn’t keep going this way. That’s when I made the decision to retire early and focus on my health and family.

(Related: What Happens When Doctors Don’t Listen to Patients)

My Parkinson’s still progressed, but I made more of an effort to manage my disease. I started eating more fruits and vegetables, and fewer processed foods, which is generally recommended for patients with Parkinson’s (though exact nutrition plans vary based on an individual’s symptoms and medication side effects). I began exercising regularly, doing not only cardio training but also weights for strength and to prevent bone thinning, which often happens with Parkinson’s. I took up yoga for flexibility. I have fallen into a routine to the point where if I missed a workout, I would feel noticeably worse.

For many of the 100,000 Canadians living with Parkinson’s, the pandemic threatened these routines. Since retiring, I have focused on advocacy and education, working with multiple organizations, including Parkinson Canada and the recently created PD Avengers, a global alliance of advocates striving to end this disease. While conducting webinars and speaking events, I heard from numerous people experiencing anxiety related to loneliness and isolation, challenges accessing their medical team or issues maintaining their fitness during lockdown.

I’m fortunate I wasn’t impacted in the same way. Two of my daughters returned home from university during the pandemic, so for the first time in a long time, all three of my girls were home. The house wasn’t a quiet, isolating place. Actually, it’s been a lot of fun. On any given evening, we’d be cooking, playing board games or watching movies together. Sure, there were times when we got on one another’s nerves—we’re not immune to that—but knowing we were in the situation together made us tighter as a family.

(Related: First Person: I Knew Something Was Wrong, But Neurologists Were Telling Me I Was Fine)

We’ve always been open about my Parkinson’s, but in the past, I tried to shield my kids from a lot of my symptoms. If I wasn’t well enough to go out or play games, I would push through anyway. I didn’t want my disease to impact their lives.

With all of us living together during the pandemic, my girls and I had conversations that wouldn’t typically happen over the phone or when they’re just home for the weekend. It was eye-opening to hear what it’s been like for them to have a parent with Parkinson’s and to learn that by hiding those weak moments, they felt I wasn’t being open with them.

On our hike up to the caves, there were steep inclines and loose rocks, obstacles that can trip up my balance. There were a few points, looking at the trail ahead, when I thought, I don’t know if I can do this. But I kept my head down, watched my footing and powered through—and when my mental fortitude wavered, my family stepped in. My daughters intuitively knew when I could use a hand to physically pull me across up the terrain, and they cheered me on, saying, “You can do this! Just one more step!”

When my family and I reached the top of the trail, I stood in the shade of the cave and looked out onto the lush forest greenery. I felt powerful. As I watched my girls exploring the paths nearby, I realized there was no obstacle—be it loose pebbles or the progression of my Parkinson’s—we couldn’t overcome.

Next, learn how the pandemic affected eight women’s mental health.