“I Didn’t Know How to Be His Mom Anymore”

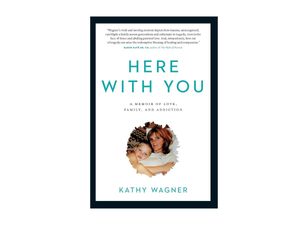

In this excerpt from Here With You author Kathy Wagner shares how she supported her son as he struggled with drug addiction.

In her book, Here With You, Kathy Wagner writes about the agonizing years she spent helping her teenage son navigate the cycle of substance-use disorder and relapse. It was an impossible balancing act of knowing when to provide unconditional support to her son, Tristan, and when to set hard boundaries, despite every parental instinct telling her to intervene.

Wagner, a single mom of three kids, recounts how she tried to ignite other passions in her son and distance him from the friends he was using drugs with in Coquitlam, B.C., including sending him to China to study kung fu with Shaolin monks for months at a time, and later helping him enroll in culinary school.

In 2017, after years of watching Tristan pinball between periods of sobriety and active addiction, Wagner would get the phone call she dreaded: He had suffered a fatal accidental fentanyl overdose, likely due to the contaminated drug supply.

Her heartbreaking memoir explains what it’s like for family members and caregivers experiencing addiction alongside their loved ones, their identities often intertwined in a co-dependent tangle.

In this excerpt, Wagner details an earlier, tentatively hopeful day a few years into Tristan’s addiction, when he had finally agreed to go to an in-patient treatment facility.

—–

I lay awake listening to the chickadees. I usually wanted to wring their sweet little necks. Anybody who chirps so loudly at three-thirty in the morning deserved a good swat, I figured. Pulling a pillow over my head to block their predawn jubilation was more my style, but on this particular morning they kept me company as I stared at the ceiling of my dark bedroom. They felt like friends bolstering my strength for whatever daylight would bring.

Their innocent songs held me while I listened for Tristan to come home. Home. He hadn’t lived with me for almost a year, but it still seemed like his home was with me.

I prayed he’d remember today and have the strength to face it. I didn’t know who I was praying to, but I prayed Tristan was alive and not damaged beyond repair. I imagined my prayers calling to him, finding him, guiding him home. I spent all night praying and trying not to cry. And almost succeeding.

Dawn had lost its glow by the time I heard the front door close and his sneakers thud in the hallway. Sweet relief lasted a brief second before anxiety caught up with me again; one hurdle down but many more ahead.

Today was the day Tristan had said he’d go to rehab. Finally, he’d agreed to use his education funds to do it. But time was not friendly to addicts, and every minute of every hour offered a thousand ways and reasons for him to change his mind.

I breathed in; I breathed out. I noticed my jaw clenching and tried to relax but my neck still twinged, and my stomach roiled. I decided to get my tea. Just don’t look at him, I told myself. It doesn’t matter. He’s here; that’s what’s important.

I found my housecoat in the pile of clothing on my floor and went downstairs, glancing at the lump on the couch. I didn’t let myself think as I made my cup of Earl Grey, focusing my mind on the mundane task in front of me, a task I could control: boil the water, get the tea bag, add a splash of milk, sit down in my chair by the window, look outside. Success.

I mindlessly watched birds flit from branch to branch. It struck me as odd that they could carry on as if this were any other day, as if there were anything more important in the world than what was happening inside, here, today.

Nine months earlier, I’d moved Tristan out of my home and into his rented room. The amount of time I’d needed to conceive and give birth to him was all he’d needed to burn his life to the ground, twenty years later. Amid the wreckage, though, there was hope. Today, there was hope.

It had been less than two weeks since Tristan had texted me in Mexico, finally admitting he needed help. He knew he couldn’t keep a job and had given up trying. He was behind on his rent and his landlord was kicking him out. If he didn’t do something he’d be homeless. That something needed to happen today.

I finished my tea, now cold, and looked outside. Soft morning light had given way to the stark brightness of day. Time to put my thoughts aside and focus on what needed to get done. Tristan had to call the rehab centre before noon, or he’d have no place to go. They’d held a bed for him all week and this, they said, was the last day they’d keep it for him.

I hauled my carcass out of the chair, put my cup in the sink and then went to look at my son. My breath caught when I saw his beautiful face, now scabby and gaunt with a newly swollen lip. I didn’t let myself feel the pain rushing through me when I saw him. I held my breath when I dialled the phone and passed it to him, listening to him muttering incomprehensibly. I didn’t know how they could understand him. Maybe it was enough that he grunted his assent when they asked if he was coming in. It felt like I was still holding my breath an hour later as he sat at the kitchen table, coffee untouched, lashing out at me. He was vaguely abusive, largely incoherent, and threatening to walk away from it all. I was focused only on my goal of getting him to rehab, so his words fell unfelt around me.

I looked at Tristan from across the table and gently asked him to pack his things. I was determined not to do this for him. This needed to be his decision; he was the one who needed to take action.

“Fuck off, already!” he moaned, wrapping his arms around his head as if to keep it from exploding, and then bringing it to his knees, burying his face. “You’re such a bitch.” His voice trailed off, broken. He muttered a few more muffled curses and my heart threatened to break. This is not my son, I reminded myself. This was addiction and desperation.

I tamped my emotions down and put one foot in front of the other, unthinking, unfeeling. I was just moving forward and trying my best to keep Tristan moving forward with me: cajoling him, feeding him, and ultimately telling him firmly there was no more time to delay. The treatment centre was only half an hour away, but if we weren’t on the road in twenty minutes, he’d miss his two o’clock intake time—and he had no other options.

He went upstairs, had a shower and came down with his bag in hand.

As we walked to the car, warm sunshine washed over us and Tristan stopped to take a deep breath. In that moment, he seemed almost like himself again, his face full of love, fear and fragile determination. He looked me in the eye and said, “I’m doing it, Mom,” then flashed a sad smile and put his arm around me.

My heart ached from the potency of hope and hopelessness, pride and shame, in him and in me. The final surrender. It wasn’t a soft surrender, but a desperate tap out after a long hard fight. We were betting his life on something better arising from the ashes.

“Yes, you are, love.” I smiled and hugged him back tightly, then kissed his fuzzy cheek. “You’re doing it.”

As we drove, I held my breath. I placed my finger on the auto-lock button in case he changed his mind and tried to jump out at a red light. I don’t know what I thought I’d do if that happened. Kidnap and deliver him, against his wishes, to the rehab fairies to work their recovery magic on him? God help me. But Tristan was quiet, dozing, until he suddenly sat up.

“Wait!” he said, his voice coarse and crackly. He cleared his throat and tried again. “Which one are you taking me to? I’m not going to the shitty one with all the fucking doctors. I’ll live on East Hastings before that. I want the fun one.” Earlier that week, in return for a place to stay and food to eat, I’d made him phone three rehab centres. I’d read it helps when a person chooses their treatment facility. Tristan had made the calls but had no opinion, made no choice. Thankfully, the one I wanted for him, the one I’d added to my contact list two years earlier, was the “fun” one: Westgate. On the phone, the other centres talked about their routines, therapeutic approaches, and certifications, but this one told him how much fun they have in recovery. This one talked about good food, going to the gym, dirt biking, movies, laughter, being “a part of.” Of course, Tristan wanted that one. What twenty-year-old wouldn’t choose the promise of fun over therapy? Even if it meant he had to give up smoking, as well as everything else.

“It’s the fun one,” I said, relieved I’d chosen correctly.

Tristan finished his last smoke and tossed the butt. We crossed the road to an unobtrusive low-rise apartment building, older but well kept. He carried his duffle bag with the few clothes and toiletries he’d haphazardly thrown in. Four or five guys sat out front. They each greeted us with a polite “Hi” or “How’s it going” and plenty of eye contact. One tall, good-looking guy in his late twenties stood up, smiled at Tristan and said, “Hey, are you a new guy?”

“Yeah, I guess,” Tristan mumbled, eyes down.

“Welcome. I’m Von.” He shook Tristan’s hand. “You’re gonna love it here. They’re going to fatten you up—you’re skinny, bro! Come on, I’ll find someone to do your intake.”

Von held the door and got us seated in the foyer. While we waited, half a dozen men of all ages walked past. Every one of them welcomed Tristan. Many gave me words of encouragement, too. They told me he was in a good place, that I could stop worrying and sleep again. They called me “Mom.” I smiled at them, blinking back tears at the simple feeling of being understood, of being in a place where young men smiled.

One guy asked if I wanted coffee and, when I told him I drank tea, seemed near giddy that he could get that too. He returned a minute or two later, apologizing for taking so long. “I didn’t know what you liked so I brought one of each option.” He grinned, pulling an assortment of crumpled tea bags from his jean pockets, front and back. I wasn’t thrilled about the teabags in his pockets but he seemed so earnest that I couldn’t say no. I chose Mint Medley.

An intake worker called Tristan into the office. Before I could follow, a stocky young guy in jeans and a Harley-Davidson T-shirt appeared and greeted me with a handshake.

“Hi, I’m Ben. You must be . . .” he looked down at a notepad. “Tristan’s mom. I’ll be his caseworker. Come on,” he said, putting his notepad in his back pocket and running a hand over his buzz cut. “I’ll show you around if you like.”

The centre was spread across two small apartment buildings and one large heritage home on a typical suburban street. Nothing fancy, but clean, comfortable, homey. There was a huge bowl of apples, oranges and bananas in the living room, which felt good. Nobody was starving here. Some guys were playing chess, another strummed a guitar, a few wrote in notebooks, and a bunch sat in the sunshine talking. There was an abundance of tattoos, but everybody looked healthy and happy.

Just normal guys.

I soaked it in, knowing this would be Tristan’s home for the next three months, at least. These were going to be his people. I began to hope. I wanted this so badly for Tristan. Seeing the guys, hearing their laughter, made it seem possible.

Back on the front steps I hugged Tristan goodbye, breathed him in, and told him I loved him. His arms hung at his side as I wrapped mine around him. He was uncomfortable in my hug, uncomfortable in his body. One of the guys walked by just then, chuckled and said, “Go on, give your mom a hug. She deserves it, man.”

Tristan gave me a quick hug, all edges and nerves. “Love you, Mom,” he mumbled, and went inside.

Driving home alone, I was overwhelmed by relief. I was still anxious: What if he doesn’t stay? And scared: He’s not going to stay! But above all that, I felt relief: I’ve done my part. He’s safe. I felt like I’d been holding my breath for years, almost to the point of suffocation. Now, I let it out. I could breathe.

I had so much space around me and in me. Where did all that space come from? What was I going to do with it?

I was not even home yet when my phone rang, and I saw “Westgate” on the call display. Oh god, what’s wrong? Even though I was driving, I answered the call, certain I’d need to turn around again, that Tristan had failed treatment in the first fifteen minutes and now I’d need to find him a homeless shelter. Or something.

“Hi, Kathy. It’s Ben. Tristan’s doing fine and getting settled in no problem.”

I relaxed, immediately. I noticed I was holding my breath again and let it out.

“That’s probably the first thing that crossed your mind with me calling: ‘What did Tristan do now?’ But he’s great. It’ll take some time to stop panicking whenever I call, so I just like to put that out there up front.”

“Thanks, I appreciate that,” I laughed, and then teared up at the novelty of being understood again—at knowing my fears were not unique. “You’ve done this before.”

“Yeah. You’ve spent a lot of time worrying about him. It’ll take a while not to. What I’m calling about, though, is to see if you can drop off some of his things at the house whenever you have time. He didn’t bring much with him, so any clothes or toiletries he’ll need over the next few months would be great. No rush. Whenever it’s convenient.”

I told him I’d stop by the next day. I hung up, happy to have a task, to still be helpful to my son.

The next morning, I woke from a restless sleep, sunlight streaming through the blinds. The surprising spaciousness I’d felt yesterday, which had seemed so full of promise then, now felt like emptiness. I had no crisis to manage, no problem to fix or avoid. It was Saturday, so no work. I had expected to feel more alive in my new-found freedom, giddy with the success of getting Tristan to rehab. Instead, all I felt was an absence of something with a rushing undercurrent of anxiety. An absence of what, though? I wasn’t quite sure. Maybe Tristan? Or stress? Or purpose?

I tried to focus my thoughts on what was important: Tristan was in treatment. Then, a crashing wave of gratitude filled me to the brim, and I became fully awake. When I remembered I could take Tristan’s things to him later that day, my residual anxiety washed away in a flood of happiness.

I spent the morning gathering Tristan’s clothes and doing laundry. That afternoon, I drove back to Westgate. The sky was a brilliant blue and my mood was bright. I had a suitcase packed with Tristan’s freshly laundered clothes, a new toiletry bag stuffed with masculine bathroom products, and a bag of candy—sour worms, Skittles and mini peanut butter cups. It felt good to be doing good.

As I walked up the sidewalk, into the house and then into the office, I glanced around, looking for a glimpse of Tristan. He was on restrictions for the first few weeks, which meant he wasn’t allowed to phone me, or anyone, and I wasn’t allowed to phone him. Apparently, this helped the guys settle into new routines and learn to turn to each other for support. It prevented them from continuing dysfunctional dynamics they had with other people when times got tough. Tristan couldn’t call me if he wanted to be rescued. I couldn’t rescue him. The restrictions were in place to support us both in finding a new way of being. I appreciated that.

But if I happened to bump into him, that seemed like fair game. Short of wandering through the buildings calling his name, though, I didn’t think that was going to happen. I decided to come right out and ask. Ben wasn’t in the office that Saturday so I dropped Tristan’s stuff off with another caseworker and asked if I could say hi.

“Oh, yeah, sorry, he’s out with a bunch of the guys. Went to the aquarium. Beautiful day for it,” he said, looking up from the old desktop computer he was working at. I was suddenly, inexplicably angry. On Day One, Tristan was out having fun at the Vancouver Aquarium?

I set Tristan’s bag beside his suitcase and adjusted my purse to stop it from slipping off my shoulder—finding any excuse to avoid eye contact. Did they have no idea of the stress Tristan had put me through over the past week? Not knowing whether he was going to make it here or not? Disappearing for days, and me not knowing if he was dead or alive? And what about all the shit he put me through over the past six years? And the first thing rehab did was reward him with a field trip? I’d been at home worrying—no, knowing—that Tristan was feeling alone and miserable, angry, hating the place and wanting to escape. I hadn’t even realized I’d been worrying about him until that moment. And here he was in rehab for less than twenty-four hours and was out watching belugas and dolphins—doing normal-people things I hadn’t been able to do with him for years—while I worried about him, did his laundry and bought him candy.

Maybe my reaction showed, or maybe it was just predictable.

“He’s with good people, Kathy,” the caseworker assured me. “Some of the guys in transition were going to the aquarium and bought an extra ticket for Tristan, figuring he could use a distraction. The boys here look out for the new guys.” He smiled in a way that reminded me of a proud father. “They know what it’s like. It’s early days for Tristan and he’s feeling pretty low. That’s normal. It’s important for him to see the guys having fun in recovery, to know he can be ‘a part of.’ He’s likely to feel like shit today, no matter where he is, no question. But it doesn’t do anyone any good for him to sit here and mope. He can be with the guys and see them having a good time, sober. If he doesn’t know he can have fun in recovery, he won’t stick around for long. That’s the truth.”

“Oh, that’s great,” I said, nodding my head as if it helped me look more believable. “That’s wonderful.” I thanked him and went back to my car. I was happy for Tristan. I truly was. All I ever wanted was for him to be happy, to fit in, to have good friends and do fun normal-people things. So why was I so upset?

As I tucked myself into the privacy of my car, it dawned on me that Tristan had other people to look out for him now. He didn’t need me anymore. He didn’t need my sleepless nights and endless worrying. He didn’t need me rushing out to him with fresh clothes and Axe body wash to make him feel better. He didn’t need me taking him to the aquarium. He was doing just fine. And if he wasn’t, there were other people for him to turn to, people who understood him and could support him better than I ever could—or ever had. I simply wasn’t needed anymore.

It was a tremendous loss, like every bone in my body disappeared and I didn’t know how to stand. It felt like I suddenly, truly lost my son. Our entire relationship was built around me looking after him, managing his moods, making his life work. I didn’t know how to be his mom anymore.

While Tristan was wrapped in the comfort of new friends, a new program and a new life, I was left alone with the emptiness of having him gone from mine. I didn’t have a group of people in my camp, distracting me with field trips and outings. I didn’t know how to be “a part of” or how to have fun, and there was nobody to show me.

I started the car but just sat there, hands on the steering wheel. I didn’t have anyone to go home to, nobody to wrap me in their arms and lend me their strength and tell me I’d be okay. I wasn’t upset about Tristan going to the aquarium at all. I was upset at being left behind, alone.

After all I’d done for Tristan, it didn’t seem fair.

Excerpted from Here With You: A Memoir of Love, Family, and Addiction by Kathy Wagner (Douglas & McIntyre, copyright 2023). Reprinted with permission by the publisher.