How a Routine Eye Exam Revealed My Son’s Brain Tumour

Tara Lipton, a New York City mom, will remember what should have been an ordinary summer afternoon for the rest of her life.

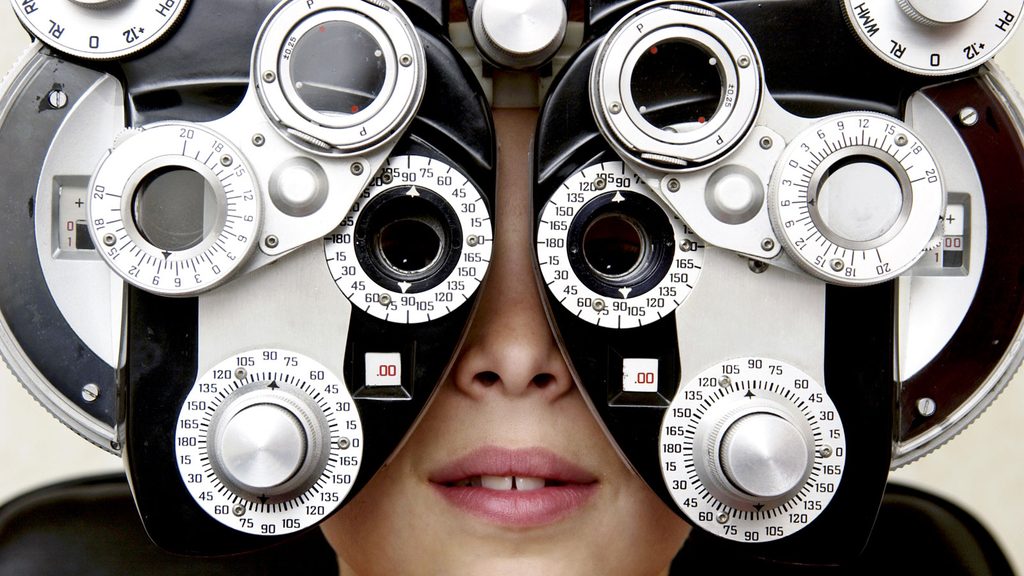

The New York City mother of four had taken her youngest son Walker, then 6, for a routine eye exam and the doctor told her that her son needed an MRI.

“I asked ‘when?’ and she said ‘now,'” she recalls. An MRI of his brain quickly confirmed what the doctor suspected. Walker had a medulloblastoma, the most common type of childhood brain tumour. During a routine exam, eye doctors can detect changes in the field of vision or swelling of the optic nerve that may indicate brain cancer.

Brain and spinal cord tumours are the second most common cancers diagnosed in children. According to the Canadian Cancer Society, approximately 935 children under the age of 14 were diagnosed with brain and spinal cord tumours between the years of 2009 and 2013.

Brain cancer can have symptoms like nausea, difficulty speaking and seizures, but Walker’s diagnosis came out of nowhere. “Like any kid, he just loved having fun, being with his brother and sisters, going to school—there was absolutely no reason to imagine he had cancer,” his mom shares.

Lipton is well-connected and was able to assemble a dream team of oncologists and surgeons to help save her son’s life immediately after diagnosis. She is a board member at the Children’s Cancer and Blood Foundation and had just served as co-chair for the group’s big fundraising benefit so she literally had some of New York City’s top cancer experts on speed dial, although she never expected to use these numbers for such a personal reason.

“The surgeons were able to surgically remove 100 percent of the tumour,” she says. “We are very lucky.” After the surgery, Walker began a rigorous regimen of radiation and chemotherapy to kill any errant cancer cells. With their three older children away at summer camp, Lipton and her husband focused entirely on Walker and his recovery. Their summer was punctuated with visits to the emergency room whenever Walker got a fever to make sure his chemotherapy port wasn’t infected, among other scares.

Now, it’s been two years since Walker finished cancer treatment.

He still goes for regular MRIs to make sure the tumour hasn’t returned and so far, so good. But the turn of events has changed his family forever. “We know how fragile life can be,” his mom says. Instead of wallowing in “why me?” and “why us?”, Lipton has channeled all of her energy into raising money and awareness for earlier detection and better, more tolerable treatment of children’s brain cancer. She is working with the Children’s Brain Tumor Project and helped raise $450,000 for rare and inoperable childhood brain tumours during their most recent benefit. “Pediatric cancer is not sexy and it has not gotten the attention that it needs. This has become my life’s mission,” she says. (Psst: Here’s what you can do to help a cancer patient.)

Lipton doesn’t want other children to go through what Walker did.

Many life-saving cancer therapies can cause collateral damage and the dosing and regimens have been the same for more than 50 years. Walker now sees an endocrinologist because the radiation affected his thyroid and the chemotherapy caused reflux which still affects his appetite. (To calm your mind, you might also want to read up on the everyday things you thought cause cancer—but are actually harmless.)

Chemotherapy and radiation provide a cure, but this often comes at a cost, says one of Walker’s surgeons, Mark M. Souweidane, M.D. F.A.C.S., F.A.A.P, vice chairman, Department of Neurological Surgery and Director, Pediatric Neurosurgery Weill Cornell Medicine/NewYork-Presbyterian. “Kids survive but they can have stunted growth, cognitive delays, academic decline, and secondary cancers,” he says. But “if we have genetic and molecular profiles that give us a good sense of the tumour’s behaviour, we can know if a cancer has a better prognosis and can reel back therapy and look at deescalating radiation and lowering chemotherapy doses to reduce toxicity while maintaining survival.”

The way doctors look at and approach cancer has changed dramatically in recent years. “We want to understand the molecular and genomic basis for cellular behaviour,” he says. “We are increasingly able to sequence brain cancers for their genomic make-up and are working to find new, less invasive ways to deliver drugs to tumour sites.”

The goal and real hope is to find a drug that attacks the specific genetic signatures of a given tumour, says Souweidane. This has become a reality in many cancers including the potentially fatal form of skin cancer melanoma as well as breast, lung and kidney cancer.

What the future holds for treating brain tumours in children.

In the future, “I would like to see an imaging system where we can identify brain tumours at the DNA or molecular level, much better avenues of drug delivery so we have tools to get more drug where we want it and less where we don’t,” he says. Dr. Souweidane’s pediatric neurosurgery research lab is part of the Children’s Brain Tumour Project and is focused on the promise of local delivery in treating brain tumours in children. Such local delivery would allow the drug to get passed the blood-brain barrier, which is tasked with protecting the brain from anything toxic in the blood.

It’s parents like Lipton and the advocacy work and fundraising they do that is helping to make a difference.

Next, learn the most common types of cancer in Canada.