What I Learned Writing a Book About Someone Else’s Death

Toronto journalist Dakshana Bascaramurty spent four years documenting the life of Layton Reid, a 33-year-old wedding photographer and new dad fighting a terminal cancer diagnosis.

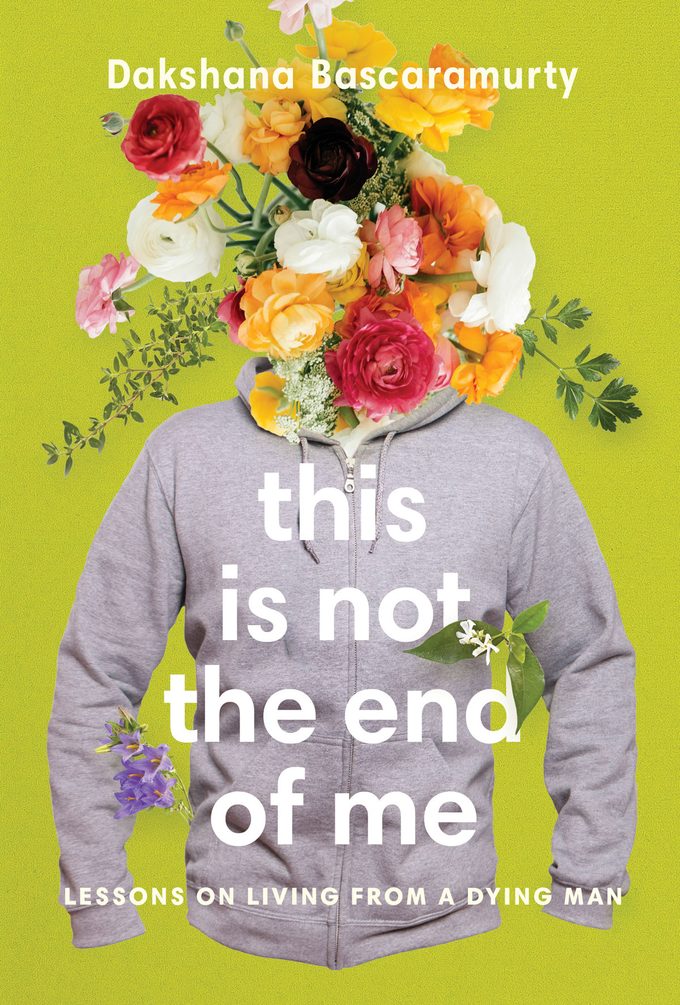

I suspected that a book titled This Is Not the End of Me: Lessons on Living From a Dying Man might not be a breezy read. Sure enough, it prompted an ugly cry for the ages, made more unsightly by the cereal and milk I was trying to eat at the time – even over breakfast, I couldn’t put it down. But what surprised me about this book is that it’s also so full of light.

Toronto-based journalist Dakshana Bascaramurty fell into Layton Reid’s life almost by accident. She hired the photographer to shoot her Halifax wedding after seeing his work online and appreciating his different lens on the world. A year later, the tables were turned when Reid, 33, invited Bascaramurty to document his life, which had just been shaken by a terminal cancer diagnosis, shortly after learning he was going to be a father.

Bascaramurty, Layton and his family spent the next few years ricocheting between the highs and lows of parenthood, an unpredictable illness, and his imminent death. She shines a light into the darkest parts of the journey with incredible empathy, and lets Layton speak for himself through a series of letters he wrote for his son.

The result is an unflinching, intimate look at what it’s like to live, as a new parent, with a terminal diagnosis, the need to maintain hope and the crushing toll caregiving can take on families. But ultimately, it’s a love story.

We talked to Bascaramurty about what Layton taught her about living, dying, everything in between and what lies beyond.

The start of your own story with Layton is so unique. Tell me more about how this book came about.

I expected to have the normal kind of relationship one has with their wedding photographer. But he was an unusually cool person, and we just had an incredible connection that day. I logged more hours with him than with my husband. Then we went our separate ways, and that was that.

A year later, in the fall of 2013, I got a note from him explaining that he had received a diagnosis. Nobody in my life at that point, at that age, had ever faced what I quickly learned by Googling was a terminal diagnosis. It was such a startling thing.

So we started emailing. He was interested in finding a way to document what was going on. I suggested we could have a conversation, and I could record it. As we kept talking, I knew this was a story I wanted to tell, both from his perspective and that of other people in his life as well. Because I could see there was a hell of a lot of sacrifice and resentment and selflessness happening on the part of his mother and his wife and son, and I wanted to know about all of that.

It’s such a deeply personal and messy thing to witness. Did you have any reservations or second thoughts?

Initially, my approach was so heavily weighted in the role of journalist versus friend – I thought I could get knee-deep in it without being scared. I didn’t know that Layton was someone I would develop a great affection for. And with the worst scenario being inevitable for him, I also half thought Layton or his family would be the ones to put on the brakes. But I think both of us were intrigued about what this could become. (Related: Read an excerpt from This Is Not the End of Me).

It feels like you take on the role of therapist, especially for his family members. Did that get complicated?

It was sometimes uncomfortable. I work at a newspaper and I’ve had it drilled into me to keep some separation from the issue I’m reporting. But this was something brand new. And Layton was always open to talking about anything. He was always saying everything was up for grabs, and that he didn’t want me to censor him or feel the need to protect him in any way. His family was the same. I can’t remember a single time they said to me, “This is just between us,” or “Don’t put this in the book, but …”

That’s a remarkable amount of trust. Especially from Layton, who knew he wouldn’t be around to see what you wrote.

In some ways, I think it was easier to trust me than [to trust] other people in their lives, because I wasn’t offering any kind of unsolicited opinions or advice. I think that happens a lot with people who are dealing with illness — friends or acquaintances or co-workers offer well-meaning advice that becomes exhausting. I was someone who just listened and let them talk and let them burn off steam.

They also sometimes needed to vent to someone outside their immediate circle. They were all in this thing together. There was a positivity that needed to be maintained, and a feeling that if there was ever a weak link, the whole thing could tumble. So sometimes they couldn’t be real with each other, but they could be with me.

Did being so close to their experience, their fears and ultimately their grief, change you?

Absolutely. This was the first death that I felt in an acute way. It was difficult and I sometimes had to make space for myself to grieve in a way that I didn’t expect. I had found a way to balance my own emotional investments in Layton and in his family with that distance needed to document what was going on, but those last three months of his life — that’s when things got a bit tangled up and scary for me. At the end of his life, it was difficult for him to directly communicate with me, so every couple of days when I didn’t hear from him or [his wife] Candace, there was that panic, that feeling of helplessness.

Throughout the book, you include journal entries and Facebook posts that Layton wrote to his son, verbatim. Why?

I felt like I couldn’t do justice to the kind of person Layton was without them. He was such a unique and darkly funny but also beautifully optimistic person. There’s really no better way of conveying that than through his own writing. It captured the evolution he went through. At the start, he’s writing as if he’s going to get through this. But then, as he comes to accept his fate, his writing, and the way he speaks to his son, changes. The raw and unapologetic way he wrote about what he was facing — it’s just so rare to see that.

The last pages are a very clear-eyed, almost technical description of what end of life looks like. I didn’t expect that.

There’s a turning point that all of them reached, where they came to terms with the fact that Layton was going to die, but all had a shallow understanding of what that would look like. If one of the goals of this book is to help people prepare for the end, I needed to describe it, and show that it’s not one final moment. There’s something just so beautiful and also mundane about waiting for somebody to die at home. It doesn’t go according to a schedule. There are all of these little scares and false alarms. You have your dreams of bedside goodbyes and all of that, but you’re not promised anything and you don’t know how it’s going to go.

I lost my own dad in April, and I think my mom had a certain idea of what the end would look like and the kind of closure she would get. But my dad was in a long-term care facility and with Covid-19, we didn’t have the chance to be in his room or by his bedside or anything. That’s the thing. You never know when the last time is going to be. I went into those last few days with my dad, knowing it could happen at any minute. And I think I was more at peace with the end, having seen what Layton’s end looked like.

Did this experience lead to any insights about how we approach death, at a policy level?

I had no idea that we even had compassionate care leave until Candace told me it was something that she was seeking. But death isn’t [always] something that happens over a day or on a weekend. So to be able to give caregivers support and time, and have it built in to workplace benefits, would be enormous. There are long stretches where Candace was working from home, or trying to work from home, while also being a full-time caregiver for both her husband and her child. That was part of why I wanted to document it in such detail — to show the extent of care that you need to offer somebody at home. Making it possible to have the support of nurses or personal support workers who can help people comfortably die at home should be a priority in Canada.

The book shows how simple our definition of caregiving is. You can see all the different types of caregivers that Layton had — one person wasn’t capable of providing all of it. And then there’s the question of who cares for the caregivers.

That’s such a great way of putting it. We talk about the immense sacrifice of caregivers and how much of themselves they put on hold to help the individual who is sick, but if they’re doing this for months, or in Layton’s case, years, there has to be people and institutional support to help them through.

I started off thinking this book was Layton’s story, but in a lot of ways, it’s also Candace’s story. One of the things I remember most was when Candace described what it was like to take long drives with [son] Finn in the car to have a place where she could cry and call her mom and confess all the fears that she could never express inside the walls of their house. She had to be strong and reassuring, but she was coming undone herself. Without her mother, she couldn’t have been that caregiver for Layton. And the sacrifices that her mom made — she knew that Candace was giving so much of herself that she was being depleted.

Are you still close with the family?

Very much so. Candace has had a remarkable second act. She has a lovely new partner now and they just had a baby. She’s still very close with [Layton’s parents] Willie and Phil. Three and a half years have passed since Layton’s death and there are still those moments where they feel the sting of grief, but it’s a comforting sting. It’s nice to not forget.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Next: Three Surgeries in Under a Year: What It’s Like Living With IBD.