Celina Caesar-Chavannes: ‘I Can’t Keep Pretending to be Something That I’m Not’

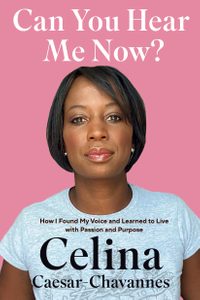

Hannah Sung talks to the former Liberal MP about her new book, "Can You Hear Me Now?," microaggressions and what the pressure to be “twice as good” does to your health.

It is very February right now. I’m spending a lot of time under blankets with snacks and feeling the push and pull of despair and resilience. The downside is that the news is still a hellscape. Covid variants, vaccine supply, political silencing of doctors, schools in a merry-go-round of locking down and reopening with no tangible measures toward greater safety. The upside? A few stories of survival.

The first came via an Instagram Live from U.S. member of Congress Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. She addressed her traumatic experience during the Capitol insurrection on Jan. 6 and also disclosed, for the first time publicly, that she is a survivor of sexual assault. If you haven’t watched, you can watch it here.

You can feel AOC processing trauma in real time. “Tell your story,” she says. It helps to process the trauma.

Her 1.5-hour video is a powerful example of using personal experience to reframe a bigger picture. Her message: No matter how often bad actors will tell us to “forget about it” and “move on,” we can’t really heal without accountability.

I watched AOC’S IG Live on the heels of finishing former Liberal MP Celina Caesar-Chavannes’s new memoir, Can You Hear Me Now? It’s a page-turner, for the same reasons that AOC’s IG Live resonated in such a big way. The story is raw honesty that shows how vulnerability and strength are two sides of the same coin.

I remember being dazzled by Caesar-Chavannes when she gave her 2017 speech against body-shaming in the House of Commons. As the only Black woman MP in Parliament at the time, she stood up to say, “Mr. Speaker, I will continue to rock these braids” in solidarity with all the girls and women who, no matter how they look or how they wear their hair or hijab, belong in schools, boardrooms and on Parliament Hill. It was a fist-pumper of a speech and I loved watching her, in Ottawa’s seat of power, being so relatable yet commanding, fierce but calm. She spoke with ease, energy and conviction.

But behind the scenes, Caesar-Chavannes was struggling. Her book reveals a dramatic contrast between her public persona — the stylish, successful woman who went toe-to-toe with the Prime Minister and walked away from the party to sit as an independent — and her private life, where she suffered from depression, was a target for online threats, and, when she hit a breaking point, required emergency treatment.

Her conflict with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will be a big draw for curious readers who want the dirt (which she delivers). But it was her life story that sucked me in, page after page. I spoke to Caesar-Chavannes to connect the dots between childhood trauma, the pressures of being a Black woman in a white man’s world and how life’s challenges become a source of tenacity and strength.

(Related: How Trey Anthony Found Strength Through Vulnerability)

On re-examining childhood trauma

“I wrote the book from the perspective of how I felt during my childhood but also how I now view my childhood as an adult. So there’s that mash up of, ‘Oh my god, I hated my mother. She just totally broke my heart’. But she also created the person that was parliamentary secretary to the leader of a G7 country. The way my mother had to raise me, based on what she knew coming from Grenada, and how I deal with my own children, is different. But the element of needing to be strong women stays consistent.

I really learned to love the child in me that was hurt and upset and angry, and just say, ‘Hey, I understand that you’re hurt and upset and angry. But really, we’re doing okay.’ ”

On the pressure of having to work “twice as hard,” as a Black woman

“When we tell our children that they have to be twice as good, twice as smart, study twice as long, that’s not a sustainable model to live your life. You can’t be doing everything double and have it not eventually catch up to you. And I say that with a big asterisk, because clearly our parents and generations before us did it. But I want to break that cycle. Not because I believe that we don’t have to be twice as good, especially as women of colour or people with multiple intersecting identities. But I want people to understand what that pressure could do to your physical, mental and spiritual well-being, [especially] in spaces that were never designed for us.

You have to remember that Parliament was built on exclusionary principles. Women, people of colour, Indigenous people were not supposed to be there. Today that exclusion is baked into the walls of that space. And going in there as the only Black female out of 338 people. I recognized that really fast. I felt it in every picture that I walked by, these eyes glaring at me like, ‘Didn’t we tell you not to come here when we built this place?’

And I would always look at them and be like, “Why are you looking at me? I earned my right to be here. I belong here.’ ”

On writing a book as therapy

“I wrote the last two chapters as [my conflict] with the Prime Minister was happening. I’m putting all of this anger into it and I sent it to my editor and she’s like, ‘I can’t publish this.’

And then she said the magic words, ‘Do you want a book that hurts? Or do you want a book that heals?’ And I was like, ‘I want a book that heals!’ And — of course, look, I’m crying right now — of course, I have to go back and do that thing where I ask myself: Where did I make mistakes here? How was I a part of the breakdown? What lessons can I learn from this that I could impart on other people before they go and tell off a Prime Minister?’ ”

On racism and sexism’s deadly health effects

“I started to study this phenomenon called weathering. It’s micro-aggressions. It’s a death by 1000 cuts and how that weathers you. The phenomenon has been studied. It causes physical ailments, it causes mental illnesses, it causes you to actually have a shortened lifespan.

When I was in Ottawa, I kept thinking, whatever this thing is, it was killing me. I kept telling my husband, I don’t know if I can stay here. I’m scared. I decided, okay, I will play the game for a while, I will learn and keep myself a little smaller. But I kept saying to my husband, ‘The gloves are going to come off.’ And he kept saying, ‘Babe, I don’t know if you should do that because you get a little, you know, bold.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but people need me to do that. And I can’t keep pretending to be something that I’m not in this space anymore because it will eventually consume all of me.’

This is why we need to show up as authentically ourselves. Because every single mistake, flaw, guilt, shame, joy, triumph, strength, everything that we have had in our lifetime, every experience that we’ve had, has added value to us. And this is why we are an asset when we go into these spaces, into our community, into our schools, but we tend to hide those things and we keep making ourselves smaller to fit into some pre-designed box that was never designed for us to fit in there. It’s counterintuitive.

On the vulnerability of telling your truth

I realized, especially in the last days of my political career, that the basic tenet of our democracy is our humanity, how we treat one another. And we can’t treat one another the way that we’re supposed to, if we know nothing about each other. And so, in being very vulnerable in this book, I’ve been intentional about removing that Instagram filter to just say, look, this is who I am.

I’m really passionate about mental health and equity. I want people to know that, yeah, I get it.

I want to create space where people have the freedom to just breathe a little bit, to breathe and say, I can be me, I can be authentic.

Hannah Sung’s column appears monthly(ish) on Best Health. It’s adapted from her (excellent) newsletter, At The End Of The Day. If you’re interested in reading more, sign up for it down below or click here.

Next: Christa Couture: ‘I Decided to No Longer Be in Disguise’